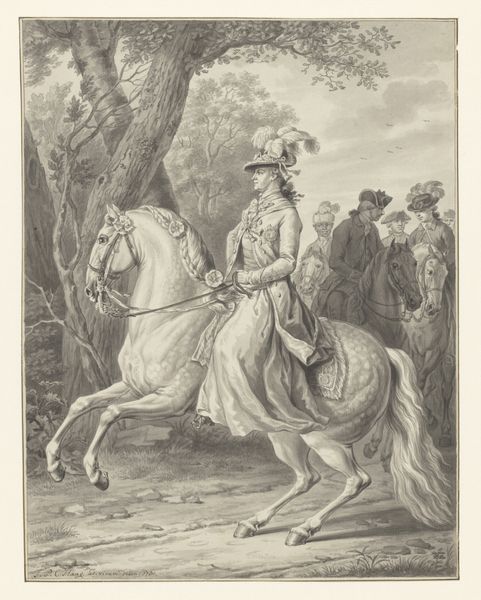

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

erotic-art

Dimensions: height 394 mm, width 262 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have an engraving from 1733, “Ruiterportret van Paul de Beauvilliers," or Equestrian Portrait of Paul de Beauvilliers, by Nicolas Gabriel Dupuis. It depicts a nobleman on horseback, set against a landscape. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is the incredible detail achievable with this printing technique. It’s so precise, especially in the horse's musculature and the rider's clothing. I wonder about the labor that went into producing this. Curator: The production context is crucial here. Dupuis was working within a well-established printmaking tradition, catering to the demands of portraiture for the aristocracy. These prints were often distributed amongst family or allies. Editor: That makes sense. The materials involved, the copperplate, the inks... each element has its own story to tell about the means of production and consumption during the Baroque era. And of course, the paper itself, a carefully crafted surface. Curator: Precisely. Think about the social function of prints in disseminating images of power. Equestrian portraits were common vehicles for projecting authority and status, linking the subject to military prowess and nobility. Who saw this and where? Did the Marquis even sign off? Editor: It's interesting how the artist plays with light and shadow using just lines. The tonal gradations must have required a deep understanding of the materials and the printing process. But who ultimately dictated this portrayal, who dictated which items of clothing? Was this all part of a well crafted visual campaign? Curator: Definitely. There's a conscious staging of the figure within this pastoral setting. It links Beauvilliers not just to aristocratic lineage but to a sense of control over the natural world, too. Land meant political influence, access to resources. Editor: So the print becomes a material representation of those claims, a portable claim to land and lineage. Each line etched into the plate represents a piece of that larger social puzzle. This artwork is not just what is appears to be at surface level, but what has had to physically take place in order for this to exist as it is. Curator: Exactly. It really highlights how images aren’t neutral; they actively participate in constructing social and political hierarchies. It encourages us to consider that role and that effect. Editor: Thinking about the social lives of images and all of these rich levels helps me understand that this particular image reflects material labor. This isn't just an image, it's also an industrial item. Curator: Yes. From that point of view, one also is made to recognise the social structure.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.