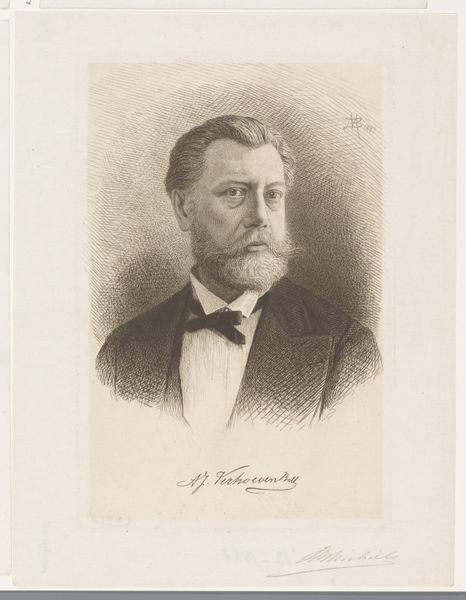

Fotoreproductie van een geschilderd portret van August Allebé after 1886

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 141 mm, width 115 mm, height 213 mm, width 138 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This gelatin silver print at the Rijksmuseum is catalogued as a photographic reproduction dating after 1886, made after a painted portrait of August Allebé. The original painting was completed circa 1886 by Princess Reuss. Editor: Well, first impression? It's a bit somber, wouldn't you say? The tonality, that dark suit against a background that almost swallows it… very understated, bordering on melancholy. Curator: I agree, but perhaps that's precisely what was intended. The portrait emerged in a period where the sitter's social status and moral fiber were crucial subjects for painters, which dictated aesthetic choices. Considering August Allebé was a leading figure in Amsterdam art circles at the time, director of the Rijksakademie, it’s also tempting to explore its relationship to institutional power. Editor: It is fascinating to consider it a study in reproduction too, isn’t it? Photography serving to further disseminate the image of an already established figure painted by a woman who held the rank of princess. We should consider labor when analyzing such forms and its materiality to create and distribute a likeness. The choice of gelatin silver is especially notable for its relative efficiency at that time. Curator: Absolutely, and how the gender and aristocratic status of the painter intersects with Allebé's position and the mechanical reproduction of the artwork in photographic format also invites conversation around notions of access and authority. The painting's transformation into a gelatin-silver print democratizes the image in one sense, allowing it to reach a wider audience, but the subject remains firmly embedded within the elite circles of late 19th-century society. Editor: Yes, it brings into focus the contradictions inherent in representation—the portrait flattens hierarchy by allowing everyone access to an image, yet it cannot fully dismantle the systems from which such hierarchies arise. This work invites us to delve deeper into those dynamics and the systems involved in reproducing artwork. Curator: Precisely. This portrait serves as a reminder that representation is never neutral; it is always loaded with social and political implications. Editor: A good reminder indeed; these images ask us to contemplate our past—the structures that came to create such social divides and labor discrepancies—which inevitably informs the present and propels us to seek means for structural changes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.