drawing, print, etching, paper, engraving

#

drawing

#

aged paper

#

baroque

#

pen drawing

# print

#

etching

#

old engraving style

#

sketch book

#

landscape

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen and pencil

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

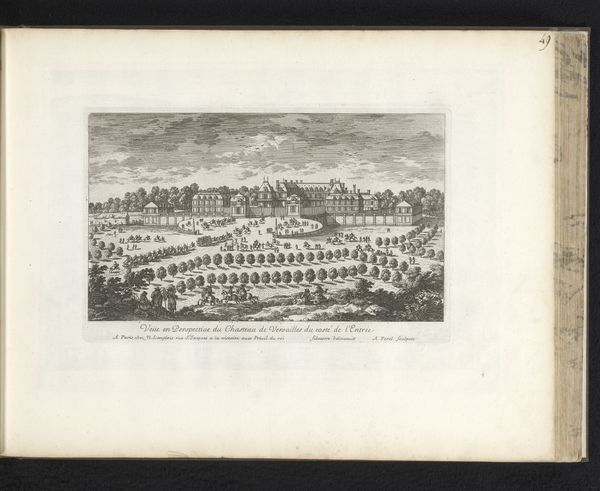

Dimensions: height 220 mm, width 301 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

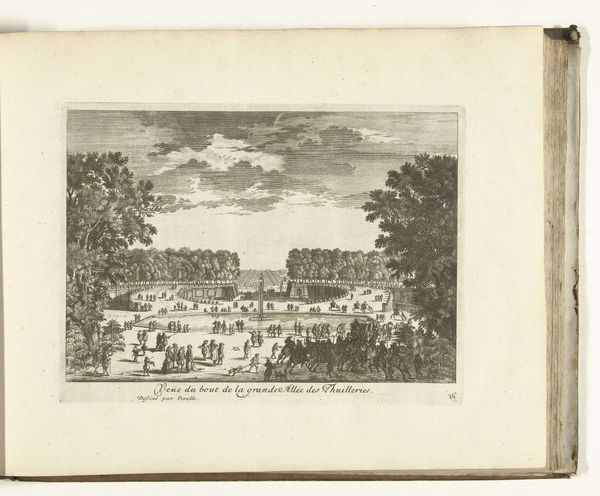

Curator: This artwork, held here at the Rijksmuseum, is titled "View of the Garden of Saint-Cloud." Created sometime between 1650 and 1707, the piece is attributed to Adam Perelle, and renders the gardens through the combined techniques of etching and engraving. Editor: My immediate impression is one of rigid control meeting bucolic pleasure. Look at the strict geometric layout, like a stage set, imposed onto nature’s supposed wildness, and how tiny the human figures appear within it all. Curator: Absolutely. The visual vocabulary of this image speaks volumes. Gardens like Saint-Cloud were deliberately fashioned to reflect the power and control of the monarchy. Each carefully placed tree, fountain, and pathway reinforces a symbolic order, reflecting an era steeped in the pursuit of earthly paradise but defined by stringent social hierarchy. Editor: It’s the hierarchy I can't shake off. Consider who this "paradise" was built for, and who maintained it. Those formal gardens demanded intensive labor, literally shaping the earth and pruning every bush according to aristocratic whims. Even the act of strolling through becomes a performance of class and status. Curator: Yet, in the engraving medium, we find a fascinating tension. Etching and engraving allowed for a democratized distribution of these images. Though the garden was exclusive, its image could travel, shaping ideas of beauty and power. It's a memory made available, if selectively, to wider audiences, influencing garden design and cultural aspiration far beyond the court. Editor: But isn’t there a flattening effect, too? By translating lived experience into reproducible imagery, the sheer physical labor of the garden becomes abstracted away. It presents an ideal that ignores the underlying economic structures. How can we reconcile the visual delight with the suppressed narratives? Curator: The image, for me, also evokes the tradition of idealized landscapes, often mirroring spiritual yearnings. Think of the Garden of Eden as a symbol for humanity's desired state of harmony; these manicured gardens borrow from that desire, presenting a carefully constructed allegory of power, perfection and ordered understanding of life itself. Editor: Perhaps we are both seeing a vision – me the reality, you the dream! Curator: Maybe, yes. It has given me much food for thought on the convergence of aspiration and control. Editor: And I'll leave considering who controls these images, then and now, and how they shape our perceptions of privilege.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.