drawing, watercolor

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

watercolour illustration

#

watercolor

Copyright: Public Domain

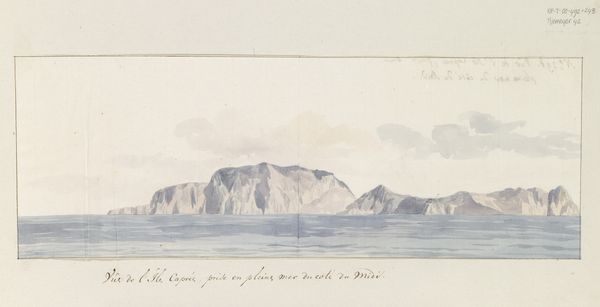

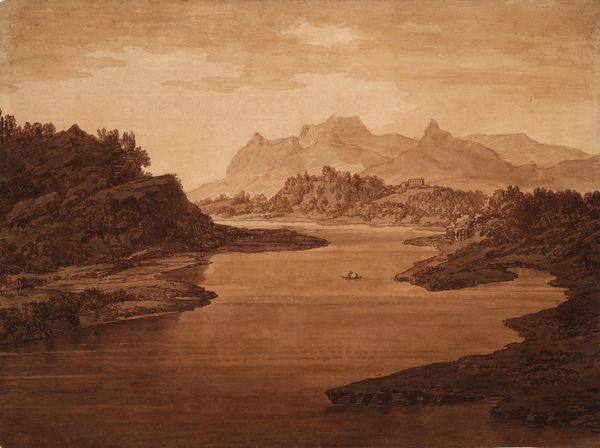

Curator: Here we have Christoph Heinrich Kniep’s “Bocca di Capri,” rendered in watercolor around 1789. What leaps out at you initially? Editor: The hazy vastness. The sea and sky sort of bleed into each other. I'm drawn to how softly the mountains on the horizon are rendered, like faint memories. Curator: Kniep was quite meticulous with his watercolors, often using them as preparatory studies for larger works. If you zoom in, you can see the geological accuracy of the rock formations, which seems quite a shift for landscape paintings. The location itself, "Bocca di Capri," translates to the 'mouth of Capri.' So he may want to deliver the "truth" of this iconic view as opposed to other artists during the Romantic period. Editor: The “truth," huh? Interesting way of framing it, as I also note those two tiny figures perched on the rocks, which almost look like they’re included simply for scale or to signify possession, something akin to mapping rather than pure aesthetics. But who is making a claim here? It may suggest that raw nature is "manageable". Curator: I see what you're saying. It’s not the untamed sublime we might expect. Though look closer—notice the contrast. The rocks in the foreground are textured and detailed, versus the sky with its even wash. This technique guides our eye, anchoring us in the material world. It may suggest the shift in interest from divine representation to earthly delight, an urge for control and even domination of land that began in the Romantic era. Editor: I am more drawn to the actual material aspect of watercolors. The labour involved would have demanded not just skill but access— pigments ground from specific minerals, quality paper made from processed fibres, a whole industry propping up the landscape tradition. Curator: And let's not forget the cultural context: Kniep was travelling around this period, collecting materials and artistic languages to render the beauty that he found and show them to the others who had no access to travelling those exotic places. It suggests that consumption, possession, and class division has shaped not just what we see, but *how* we see. Editor: Well, looking at “Bocca di Capri”, it reveals, perhaps inadvertently, the industrial backbone supporting these idyllic visions. A poetic landscape is also deeply embedded in material networks of labor and resources. Curator: And I think that it also lies between the visible, like brushstrokes in a painting, and the invisible like capital flow during his time. Interesting ways of contemplating. Editor: Precisely. It makes you rethink what exactly the work is trying to show in a larger picture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.