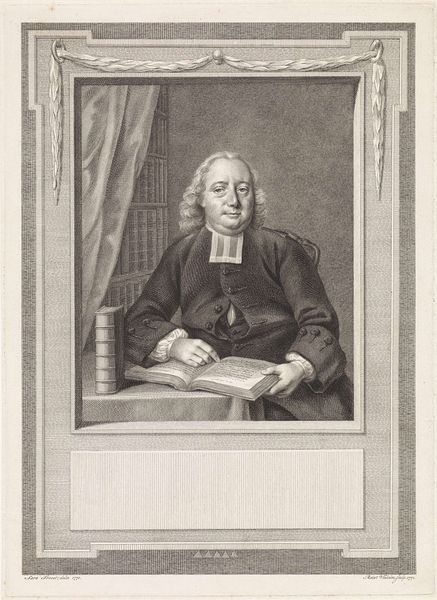

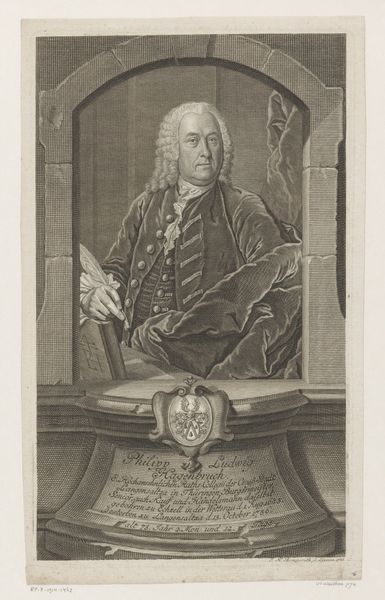

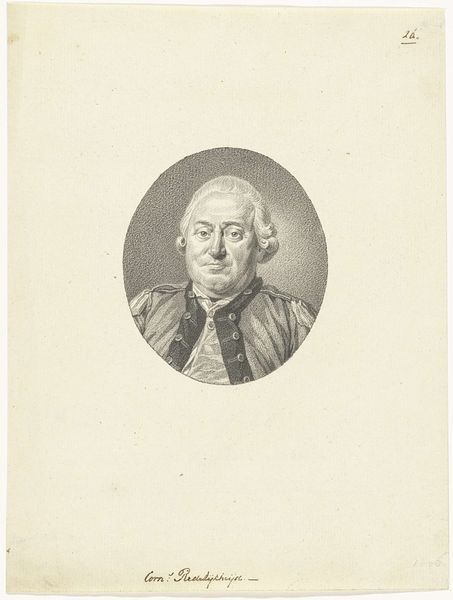

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 378 mm, width 217 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Pieter Tanjé's "Portret van Jacobus Boon," an engraving dating from 1716 to 1761, housed at the Rijksmuseum. It strikes me as a formal depiction, yet the unfinished ornamental details around the portrait add a layer of intriguing incompleteness. What’s your take on this work, considering its context? Curator: The unfinished state of the ornamental details is fascinating, isn’t it? Tanjé was working during a period when printmaking was a powerful tool for disseminating images and ideas across social strata. While baroque aesthetics favored ornate detailing, consider what leaving these flourishes incomplete might signify. Is it a cost-saving measure in print production? A deliberate comment on the subject's character – perhaps Boon was seen as a man of substance, less concerned with outward show? Editor: That’s a thought-provoking point. It makes me wonder about the intended audience for such a print. Would it have been widely accessible, or mainly for the elite? Curator: That’s crucial to unpack! Engravings, compared to painting, allowed for wider circulation, contributing to a broader, if still limited, access to portraiture beyond the sitter's immediate circle. Prints like this shaped public perception of individuals and projected a certain social standing through dress and pose, effectively visualizing a particular identity for public consumption. Does this image tell us something about how Jacobus Boon, perhaps a figure of authority, wanted to be perceived, and how that intersected with larger social expectations of leaders during this period? Editor: I hadn’t thought about how the print medium itself plays into shaping public perception! So, it’s not just about the individual portrayed, but also about how that portrayal functions within society at that time. Curator: Precisely. By examining how this image circulates and what visual messages it conveys, we can gain insight into the public role of art during the 18th century and how identities were constructed and negotiated in the public sphere. Editor: That’s given me a completely different lens through which to view portraiture. I see now it’s much more than just an individual likeness. Thanks for that deeper insight! Curator: My pleasure! It's exciting to consider how an unfinished print can unlock rich narratives about its subject, the artist, and the society they both inhabited.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.