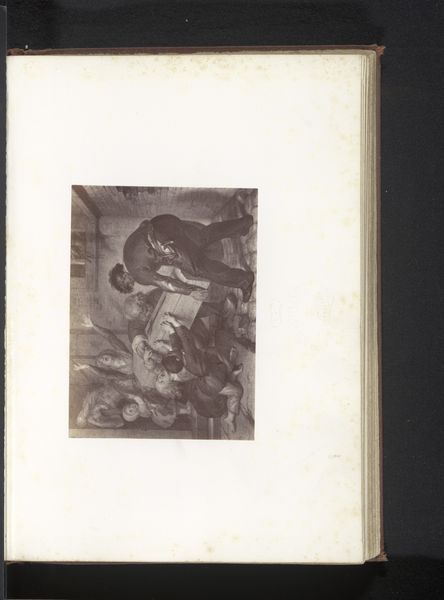

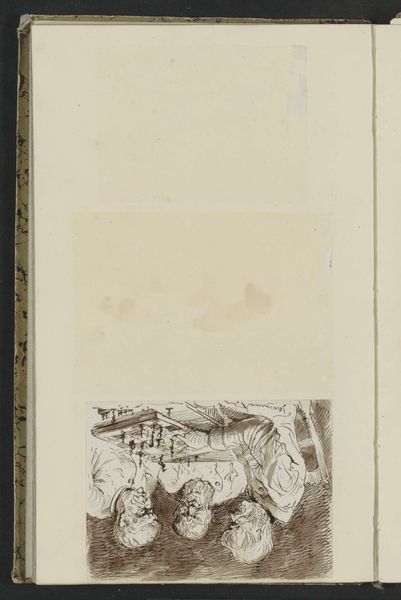

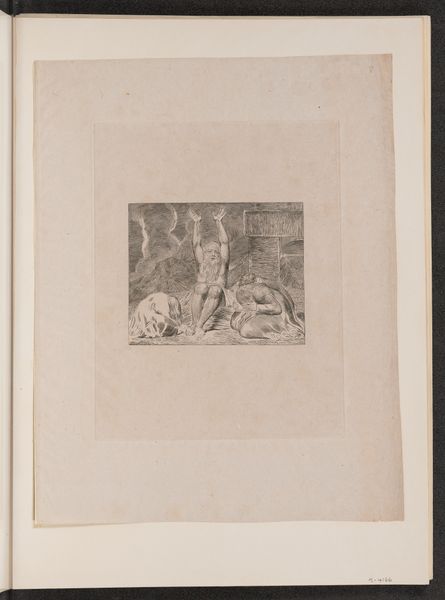

Fotoreproductie van een prent, voorstellende een soepmaaltijd in een klooster 1840

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

genre-painting

#

academic-art

Dimensions: height 95 mm, width 129 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Immediately I notice how the blurring creates an incredibly sombre tone; the contrast feels oppressive somehow. Editor: Well, that may be because this is a photoreproduction of an etching by Christian Joseph Berres dating back to 1840, entitled "Fotoreproductie van een prent, voorstellende een soepmaaltijd in een klooster," which roughly translates to "Photoreproduction of a print, depicting a soup meal in a monastery." Etching naturally lends itself to such striking tonality. Curator: "Soup meal in a monastery"... So, beyond the literal subject matter of monks eating, we should really consider the economic context of this meal. Who provides the materials and sustains such work? Is it a tithe from labor, a direct investment from some lord, or is it the products of the monks themselves? Editor: Those are good questions, though I am inclined to view it within its time period. It represents more than a simple snapshot of monastic life. It’s about visibility, and how we view poverty. Genre paintings had a rising audience by then; the artist must've known his subject matter was charged. Who eats soup in the nineteenth century, and who provides it, says a lot about social standing, don't you think? Curator: Of course. The use of printmaking to portray it suggests that it was produced for wider dissemination, beyond wealthy patrons or collectors. What was being consumed in nineteenth-century Austrian society when such works entered the economy? I am curious as to whether such items were meant for common consumption, or produced as symbolic gifts meant for high society patrons of the arts. Editor: Well, from a post-colonial lens, monasteries carry with them such fraught questions. The ways in which they function as both sanctuary for the less fortunate and extensions of social power should give us all some pause when looking at images of religious altruism. Curator: Agreed. The piece gives you much to contemplate—how production serves varied patrons, whether religious or public. The labor required to create this print parallels in many ways that of the monastic meal depicted. Editor: And together they invite viewers to ponder questions about charity, inequality, and the often complex entanglement of faith and power structures within nineteenth-century life.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.