drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

ink drawing

#

pen drawing

# print

#

pen illustration

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

pen-ink sketch

#

line

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: width 29 mm, height 33 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

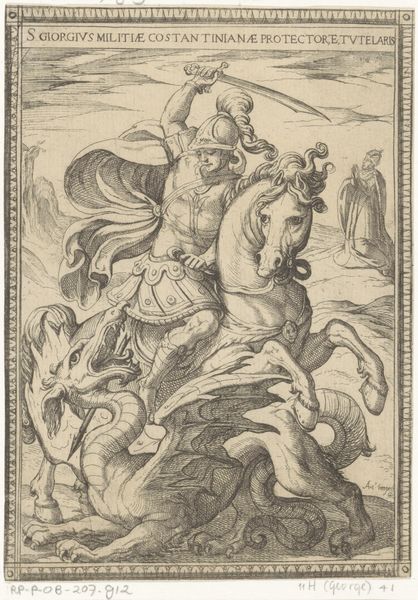

Curator: This engraving from 1567, attributed to Abraham de Bruyn, is titled "Romeinse ruiter te paard," depicting a Roman rider on horseback. The piece is part of the Rijksmuseum's collection. Editor: It has a dynamic feel; the stark lines and use of chiaroscuro lend it an urgency, like a snapshot from a crucial moment. There’s an almost performative theatricality here, don't you think? Curator: The drama is certainly part of the Mannerist style, known for its exaggerated forms. I'm interested in the way the artist uses line to define shape and create texture. Consider the meticulous hatching that models the horse's musculature and the rider's posture. Editor: But we must consider the historical implications: Roman equestrian statues were frequently vehicles for projecting power, so how does the artist reflect or challenge these ideas within the socio-political sphere of the 16th century, as printmaking expanded and knowledge of the classical world shifted? I notice the somewhat peculiar choice of the rider, who looks less authoritative ruler, more warrior brandishing a weapon. Curator: Perhaps the intent wasn’t straightforward glorification, but an exercise in representing dynamism. The tension in the horse's pose is wonderfully captured. Observe the delicate, curving lines of the mane contrasting with the coarse treatment of the background. Editor: Absolutely, and how can we neglect the historical context in an age of constant conflict in Europe, when religious and political ideologies clashed, how this symbolism affects its reception. A lone warrior carries significant connotations. Curator: From a purely art historical viewpoint, I would focus on the lineage this work belongs to: Renaissance prints and drawings, where artists sought to showcase skill. The play of light and shadow is rendered almost like an exercise in how much information one can convey in a small work. Editor: But what is the point if it isn't reflective of a larger discourse or a tool of subversion? De Bruyn invites interpretation based on these societal struggles. It becomes something more than mere illustration. Curator: True, though appreciating his command over engraving shouldn't be understated, it still adds layers of complexity. Editor: Considering these historical tensions and artistic interpretations enriches how we perceive it now. Curator: Indeed. Understanding the art solely through lines can sometimes obscure, the artist engages within his cultural landscape.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.