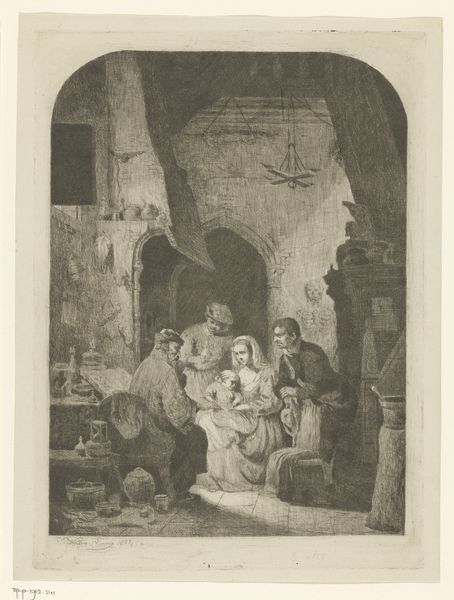

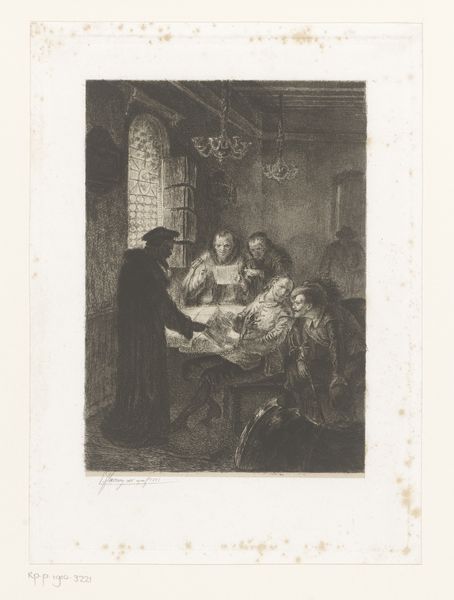

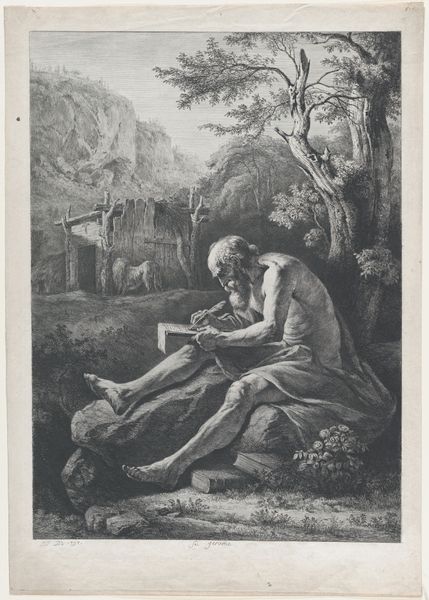

drawing, print, pencil

#

pencil drawn

#

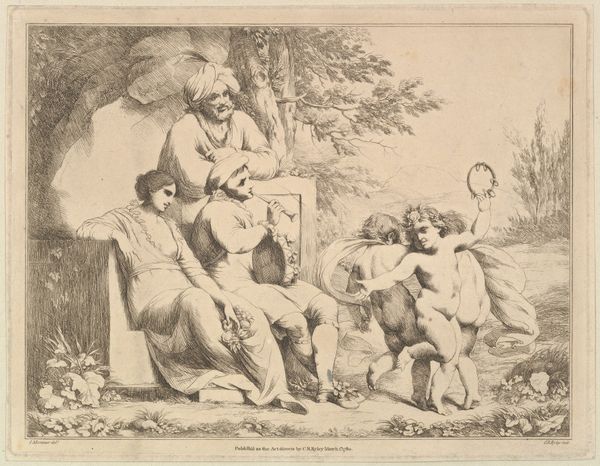

drawing

#

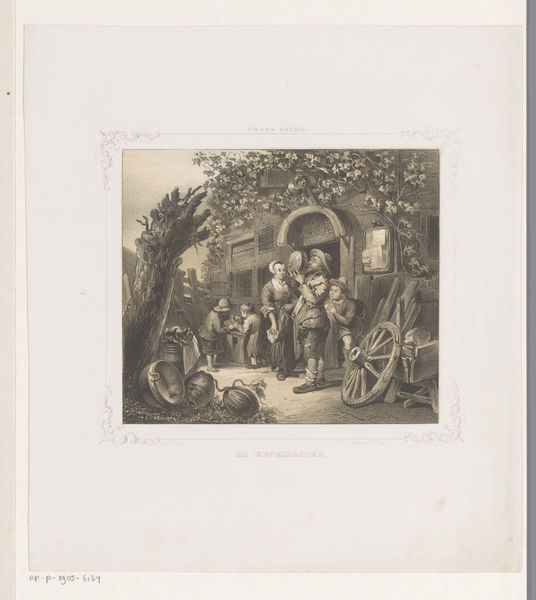

narrative-art

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

charcoal drawing

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

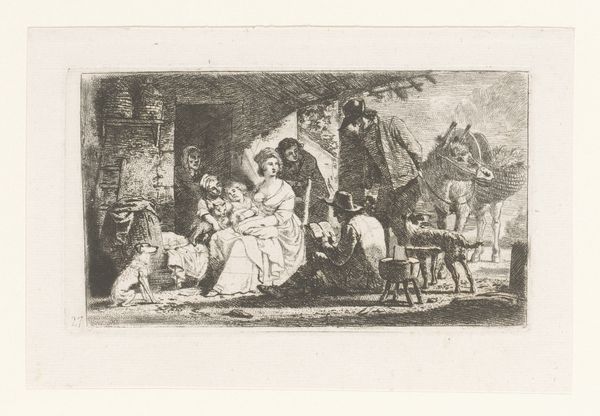

genre-painting

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 575 mm, width 428 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This drawing, "Kinderen dansen in een kring rond een oude man" by Adolf Wagenmann, dating from 1849 to 1889, presents a circle of children dancing around an older man. It feels nostalgic, like a snapshot of idealized domestic life. How do you interpret the societal values being reflected here? Curator: That’s a great observation about the nostalgic quality. Consider how 19th-century art often idealized domestic life, reinforcing specific social structures. Academic art frequently served a didactic function, presenting moral narratives. How does Wagenmann use the imagery of childhood innocence to promote a particular vision of German society? Editor: I see what you mean. The children's innocent play, the protective grandfather figure – it's a scene of harmony. Is there any tension within that seemingly perfect image? Curator: Precisely. The image carefully constructs an image of social cohesion, yet think about what might be absent. Are all members of society included in this idyllic view? Who might be excluded or marginalized by such a portrayal? This can tell us as much, or more, about its role as public imagery. Editor: That’s fascinating. I hadn’t considered it from that angle. I was so focused on the charming scene itself, but now I realize how it reinforces specific social expectations and potentially overlooks existing inequalities. Curator: Exactly. It’s a powerful example of how art operates within a socio-political context, promoting certain ideals while simultaneously obscuring others. By acknowledging this, we get closer to its complete public function. Editor: I’m leaving with a much better understanding. It's amazing to see how social context is just as important as subject and style when analyzing art! Curator: Absolutely. Art never exists in a vacuum; its power lies in its relationship to the world around it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.