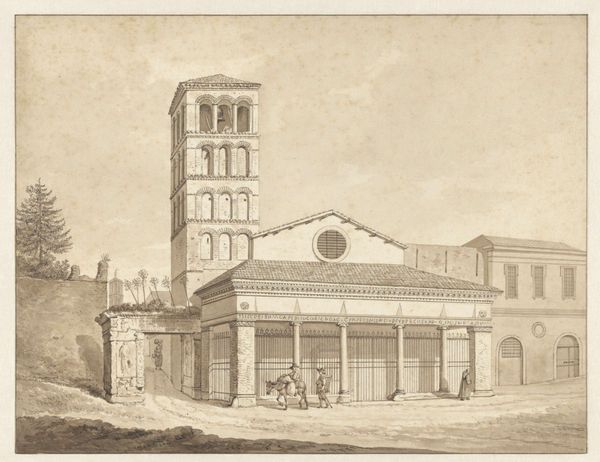

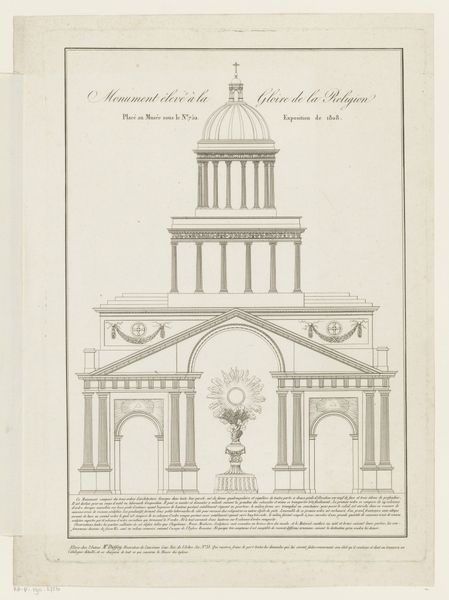

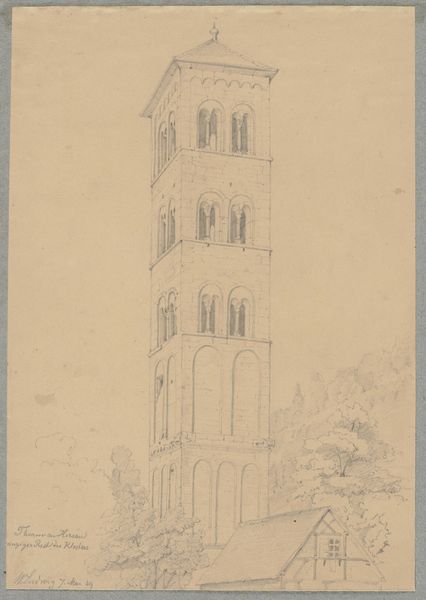

drawing, paper, pencil, architecture

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

paper

#

pencil

#

19th century

#

cityscape

#

academic-art

#

architecture

Dimensions: sheet: 29.4 x 18.8 cm (11 9/16 x 7 3/8 in.) image: 26.1 x 15.5 cm (10 1/4 x 6 1/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: The towering form we're observing is Karl Friedrich Schinkel's "Campanile of a Cathedral for Berlin," a pencil drawing on paper dating back to 1831. What strikes you most about it? Editor: Well, immediately, its austerity and sense of controlled grandeur come to mind. The sharp lines, the almost clinical rendering... it feels both imposing and, strangely, very calm. Curator: Precisely. And consider the meticulous detail rendered by the artist using pencil. Schinkel, primarily an architect, wasn’t just creating an image, he was proposing a material vision for urban space and civil engineering, all rendered using such common materials. This suggests accessibility and replicability. Editor: Absolutely, it reads as a kind of visual manifesto! Think of the message it conveyed. An aspirational urban vision became intertwined with Prussia's socio-political aspirations, particularly its ambition to reassert itself after the Napoleonic Wars. Schinkel was heavily involved in urban planning, so how did his commissions allow for his architecture? Curator: As a state architect, his commissions shaped Prussian identity by literally laying the bricks. The architecture helped in consolidating and communicating the ideals of the state. He thought deeply about how these urban landmarks could be incorporated in a civic ritual space; the sheer number of figures congregating around it illustrates that emphasis on a public experience. The choice of the drawing, a portable object in comparison to built environment is itself telling. Editor: Yes, the presence of people lends the monument an intended purpose, almost theatrical in nature! A constructed space designed for specific performances of nationhood. And is this rendering of Berlin also tinged with idealized Neoclassicism? Curator: Undeniably, but filtered through the Prussian lens. Schinkel masterfully synthesizes historical references with a distinct regional aesthetic. He also elevates drawing. Not as mere blueprints, but rather elevating art that directly facilitates shaping a landscape for the population to materialize in a particular sociopolitical light. Editor: So we’re presented with more than a city. Curator: Much more, wouldn't you agree? And much to think about, now as then. Editor: Indeed. This provides plenty of insightful perspectives on Schinkel's intention and the wider historical setting.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.