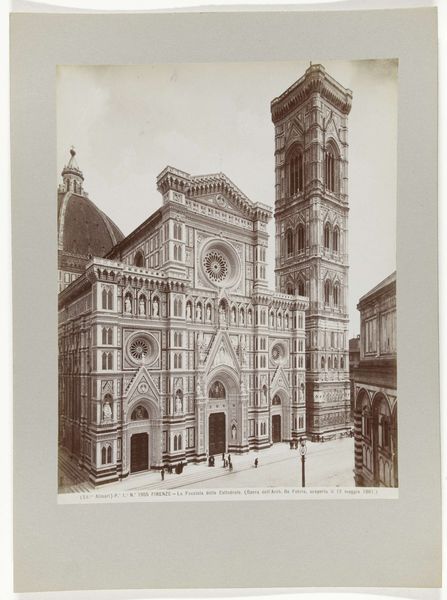

print, photography, architecture

#

16_19th-century

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

cityscape

#

architecture

#

realism

Dimensions: height 385 mm, width 274 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

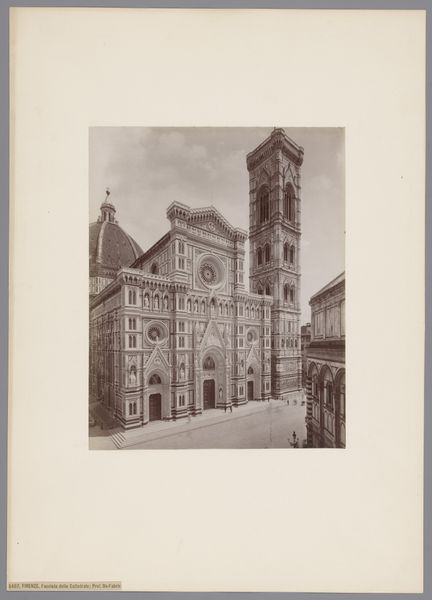

Editor: So this is a photograph called "Stadsgezicht met kerk, mogelijk in Italië," which translates to "Cityscape with church, possibly in Italy," dating from around 1850 to 1870, by Paul-Marcellin Berthier. The level of detail is stunning, especially considering the age of the photograph. What stands out to you in terms of the means of production and how it reflects the social context of the time? Curator: Given my perspective, I'm immediately drawn to the materials and processes involved in creating this image. Consider the collodion process likely used; a fragile glass plate meticulously coated, exposed, and developed. What kind of labour do you think was involved in preparing and executing such an image, versus, say, a daguerreotype, or later photographic processes? Editor: I imagine the preparation would have been quite laborious. The photographer needed a portable darkroom and had to act quickly before the collodion dried. Compared to modern photography, where anyone can snap a picture with their phone, it really underscores the artistry and craftsmanship involved. Curator: Exactly. And this craft has a socio-economic dimension. Who had the resources to engage in such a complex process? Consider the rising middle class and their desire for representation, or the colonial project and its demand for documentation. Do you see any relationship between the photographic technique, its limitations, and the way the church is represented? Editor: I hadn't considered that, but it makes sense. The photograph highlights the imposing scale and architectural details of the church, almost emphasizing its grandeur. It served a purpose to create and celebrate imposing, dominant structures that shaped our landscapes. How interesting! Curator: Precisely. The photograph becomes not just a document, but an artifact revealing production and consumption networks, from materials to skill, reflecting the prevailing social structures. This early form of image reproduction, now accessible via prints, was a commodity circulating through 19th-century society. What does that imply? Editor: It drives home the point that even something seemingly straightforward like a cityscape photograph is deeply entwined with its material and social context. It's more than just a picture, it's a product of a very specific time and place, impacting popular memory in so many ways. Curator: Indeed, by investigating the nuts and bolts of creation, the art's materiality, we unravel much wider historical narratives around technological advancement and the evolving networks of human activity that supported them. Thanks to the process of photography itself, this imposing architectural construct will remain ever more preserved.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.