ceramic, porcelain, sculpture

#

ceramic

#

porcelain

#

figuration

#

sculpture

#

genre-painting

#

decorative-art

#

miniature

#

rococo

Dimensions: 5 7/8 × 4 3/4 in. (14.9 × 12.1 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

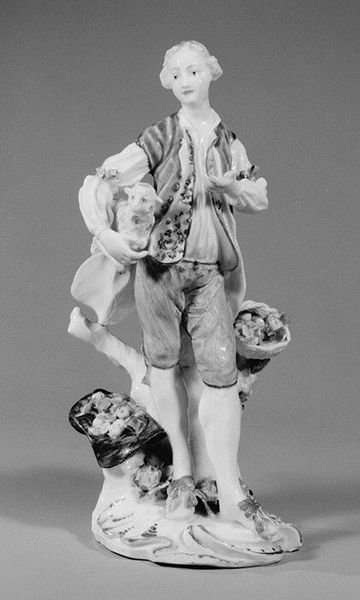

Curator: Immediately I see domestic tranquility and staged idealism. The detail is precious, almost cloying. Editor: This is Education of a Peasant, a porcelain sculpture made around 1755 to 1760 by the Höchst Manufactory. The piece gives us an insight into the ways the 18th-century decorative arts played with class and social dynamics. Look closely—how do the materials and production choices comment on societal values? Curator: Well, porcelain itself speaks volumes. Here you have a material associated with wealth and refinement, used to depict idealized rural life. The labor that goes into the extraction, preparation, and firing of the porcelain seems almost intentionally masked. Editor: Precisely. And consider the context: who owned pieces like this, and what narratives did they reinforce? Were these objects of aesthetic enjoyment, or tools for constructing a specific identity through idealized rural scenes and class fantasies? Curator: Let's look at the making. I see mold-making as well as painting here, each requiring different expertise, likely done by separate artisans within the manufactory system. It begs the question of attribution and the erasure of individual skill in favor of brand identity. Editor: The poses are so mannered, too. It is as if we are asked to passively consume an idea of simplicity, devoid of any actual engagement. How can we contextualize this imagery within larger discourses of power, labor, and representation? Is it celebrating, romanticizing, or, in a way, patronizing the lower classes? Curator: And what kind of aesthetic experience did this generate for its owner? Perhaps it served to soothe anxieties arising from the burgeoning economic shifts that threatened the landed gentry's status. This type of object serves both function and social purposes. Editor: Agreed. Examining who profits from and consumes representations is crucial, along with uncovering hidden power dynamics and raising questions of representation and appropriation. In other words, what does it mean to turn labor and identity into a miniature ornamental scene? Curator: Precisely. Seeing this today invites critical interrogation of materials and modes of production. Editor: Indeed. The art isn’t only the final object. It is the questions raised about our historical gaze.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.