drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

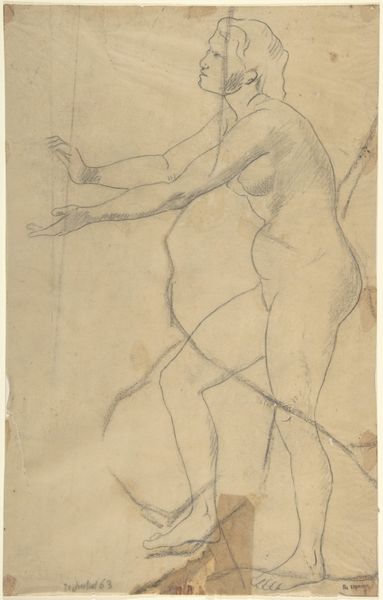

Dimensions: overall: 36.6 x 24.7 cm (14 7/16 x 9 3/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

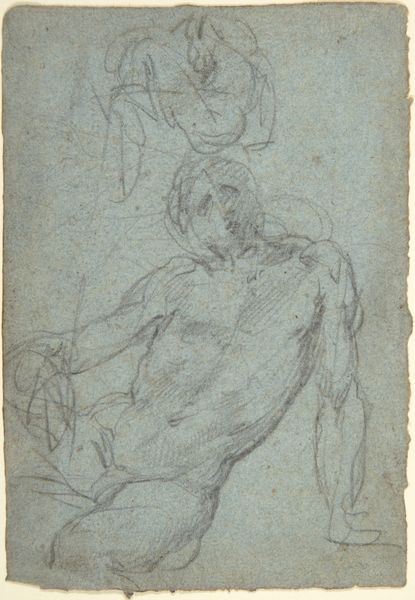

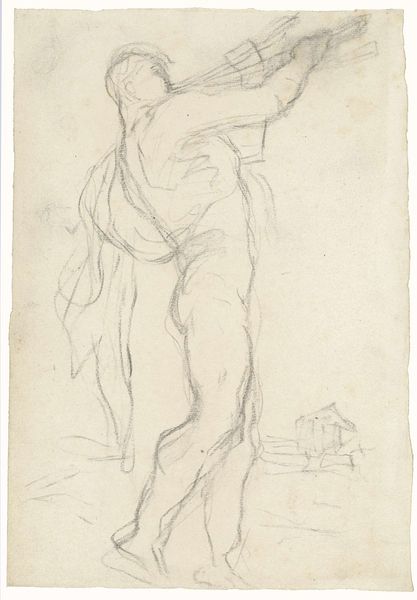

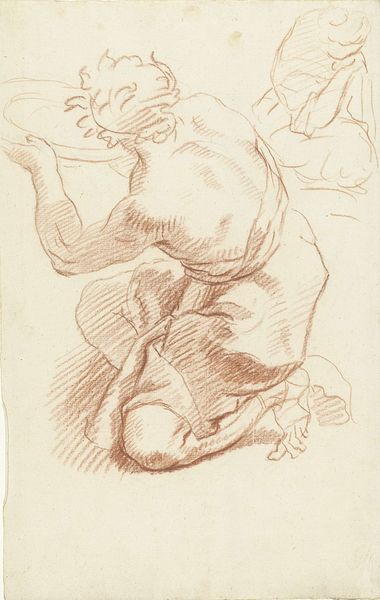

Curator: Before us is a compelling work entitled "Study for a Prophet," created between 1567 and 1573 by Lattanzio Gambara. It's a pencil drawing, a medium allowing for detailed exploration of form. Editor: It feels immediately dramatic, even unfinished. The figure is powerfully rendered but contorted, like he's wrestling with an idea or a vision. Is that a tablet he's holding? It reminds me of someone clutching at sanity itself. Curator: Precisely! The preparatory grid we can see beneath the shading speaks volumes about artistic labor and planning. Gambara wasn't just divinely inspired, but diligently constructing. The grid gives it such structure! Editor: I like seeing that under-drawing. You see his process. All these visible strata – grid, sketch, form – build up and give depth. Like layers of human consciousness all revealed together on paper. Curator: Absolutely. And it prompts consideration of workshops. Was this for his own work, or under contract for a larger project? Who supplied his materials? This nude, presumably based on a live model, was it commissioned? Who benefitted from this figure and artwork? All considerations within Renaissance art at this time. Editor: See, to me, his body feels like a landscape… like an actual site where meaning erupts. His tense musculature hints at profound exertion – not of body, but of spirit! His inward turned eyes… and his vulnerability feels like that of a city after its surrender… a city that still dreams in rebellion and creation… It resonates… but I guess it is meant to! It's called 'prophet' after all... ha. Curator: But note too, the absence of a 'finished' work can illuminate more of his labor than had this design progressed, for instance, into fresco form in a ducal palazzo, and hidden under layers of status, display, and its inevitable and problematic ties to wealth, war and display. Editor: Perhaps it's best then that he remains perpetually "in process," a becoming. I rather enjoy thinking the 'prophet' as constantly re-imagining the world into new potential. Always thinking and drawing for the potential. Curator: Well, whatever its ultimate destiny or purpose in 16th century Europe may have been, the raw physical creation is a real and concrete accomplishment. It is here. Editor: And perhaps *becoming*, that striving, is its message. Thank you! I definitely came closer to something more meaningful through understanding Lattanzio’s original intentions and creation processes with this magnificent "Study."

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.