drawing, watercolor

#

drawing

#

watercolor

#

watercolour illustration

#

decorative-art

#

watercolor

Dimensions: overall: 26.8 x 35.6 cm (10 9/16 x 14 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

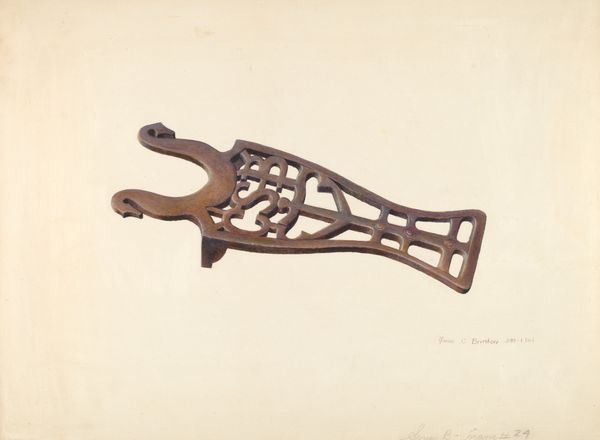

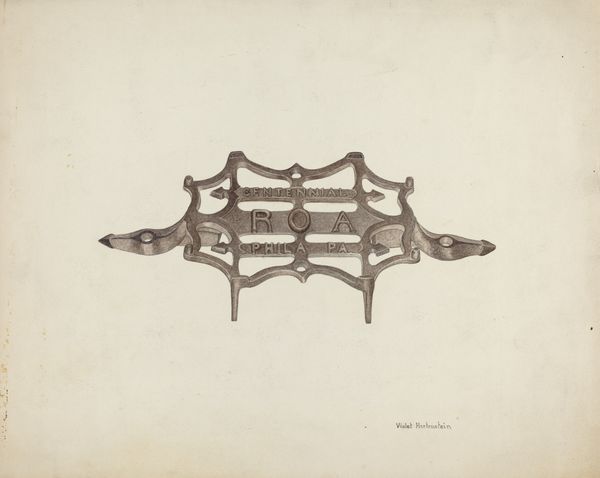

Curator: Here we have a watercolor drawing titled "Flat Iron Stand," created between 1935 and 1942 by Amos C. Brinton. Editor: It looks surprisingly elegant for what it is. There's a real stillness to the object, presented almost as an artful still life. Curator: Exactly. Let’s consider the labor involved in creating, and then in depicting such a utilitarian object. Brinton has elevated something mundane. Watercolor, of course, lends a lightness, contrasting with the heavy cast iron, typical material for the original object. Editor: That contrast makes me think about the hidden labor within domestic spaces during the early to mid-20th century. Something as basic as ironing involved physical toil, predominantly by women. The artistry here is complex because Brinton, possibly a man, draws a stand *for* an object related to very gendered labour. How might that context shape our interpretation? Curator: Well, focusing on the decorative arts aspect and considering social history helps reframe its role, or even expose uncomfortable realities. It calls attention to material culture's impact, as such objects were eventually displaced by more efficient, possibly more alienating technologies. Brinton's close rendering brings out the detail, design, and probably, manufacture quality involved in making these goods. Editor: It's about more than the individual object; it speaks to larger themes like industrial shifts and social change. Decorative art often gets sidelined as trivial. When art documents such things, as in Brinton's piece, this speaks to the devaluation of that kind of physical exertion and lived experience. I guess you could ask: Whose labour is worth representation? And how does that relate to status, class and gender? Curator: Definitely. Seeing value in these material records can, for example, show how consumption habits shifted. It brings into view production processes and what types of craftsmanship and industry communities could form, even what kinds of exploitation the objects could have supported. Editor: Looking closely, what initially reads as simply a flat illustration, begins to convey the many intersectional ways the everyday contains so much historical significance. It can really change how you look at functional objects now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.