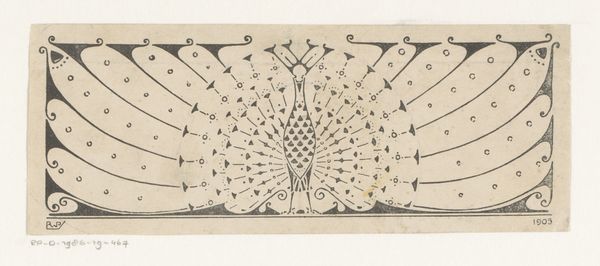

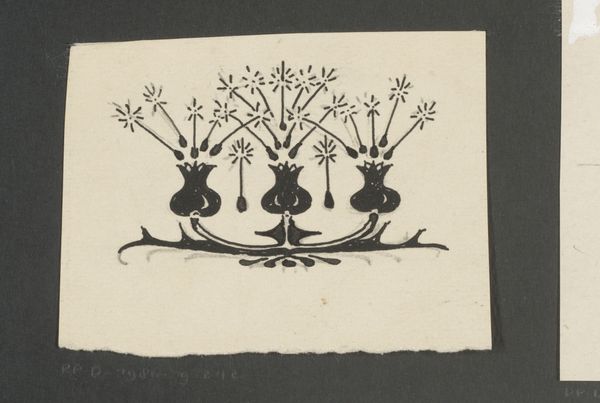

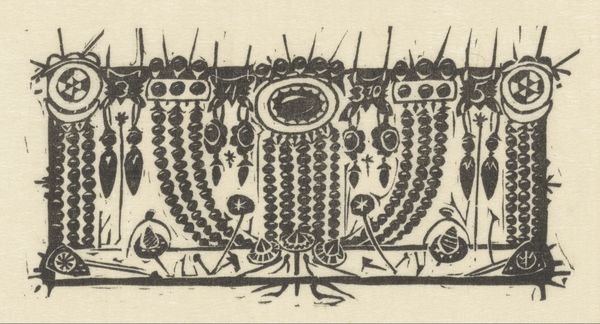

print, woodblock-print

#

art-nouveau

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

woodblock-print

#

line

#

symbolism

#

decorative-art

Dimensions: height 65 mm, width 120 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us is Gerrit Willem Dijsselhof’s “Titelhoofd met pauwen,” which translates to "Title Page with Peacocks," a woodblock print housed right here at the Rijksmuseum, and made sometime between 1893 and 1927. Editor: Striking! There’s such a weight to the dark ink on that paper. It’s not just the imagery, it feels like the material itself conveys something very intentional about value and labor. Curator: Indeed. The image is deeply rooted in Art Nouveau and Symbolism. Dijsselhof was very interested in incorporating these ideas, including the aesthetics of Indonesian art, into all aspects of the domestic sphere. Editor: So it’s not just the choice of peacocks but the entire ethos. How widely would prints like this have circulated? Was it aimed at a bourgeois market interested in craft and the handmade? Curator: Prints offered accessibility to art and design to broader audiences. There’s something inherently political in distributing aesthetics beyond elite circles. Dijsselhof helped found the Arts & Crafts movement in the Netherlands which reflects a kind of utopian reimagining of the role of design. Editor: It almost feels subversive, doesn’t it? Rejecting mass-produced ornamentation in favor of something rooted in skilled labor, even if the aesthetic is inherently luxurious through the representation of peacocks! It creates an interesting dialogue around social status, value, and taste, no? Curator: I see what you mean. Peacocks, traditionally symbols of opulence, in a format striving to democratize access to design! It highlights how Art Nouveau negotiated ideas of luxury and social reform. And Dijsselhof embraced it completely, including furniture design. Editor: Looking at the print itself, you can feel the hand of the artist so palpably. The carving marks aren’t hidden; they become part of the visual language. This print invites us to consider production in ways that paintings often don’t. Curator: Absolutely. By integrating those considerations into domestic space, it helped change perceptions of fine art as well. Editor: It makes you wonder about the artisan behind it, and about all the decisions—socioeconomic and otherwise—involved in its making. Curator: It seems like Dijsselhof aimed at social transformation with his production of such pieces. A reminder that design, like history, is never truly neutral.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.