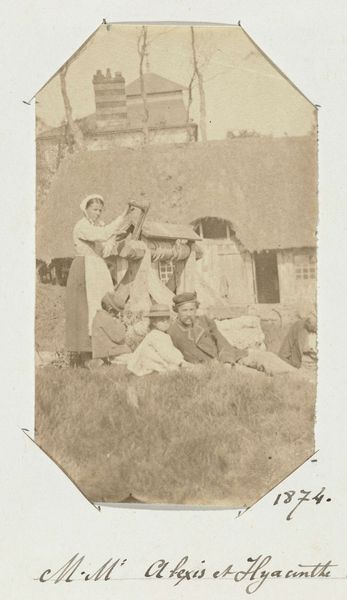

Jardin zoologique de Bruxelles; Les trois jumeaux fils de Mr. Lebens et toute la famille 1854 - 1856

0:00

0:00

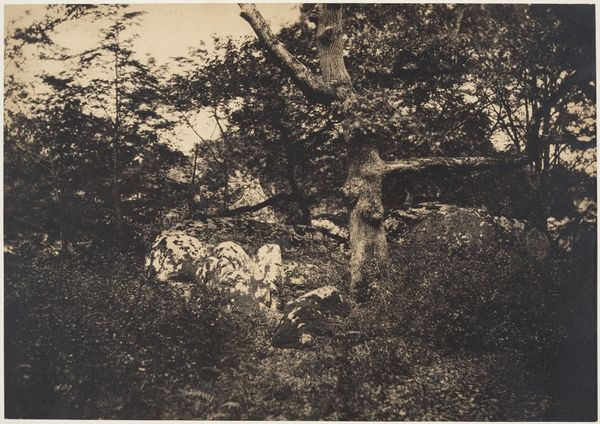

Dimensions: Image: 5 13/16 × 7 11/16 in. (14.7 × 19.5 cm) Sheet: 13 3/8 × 18 1/8 in. (34 × 46 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

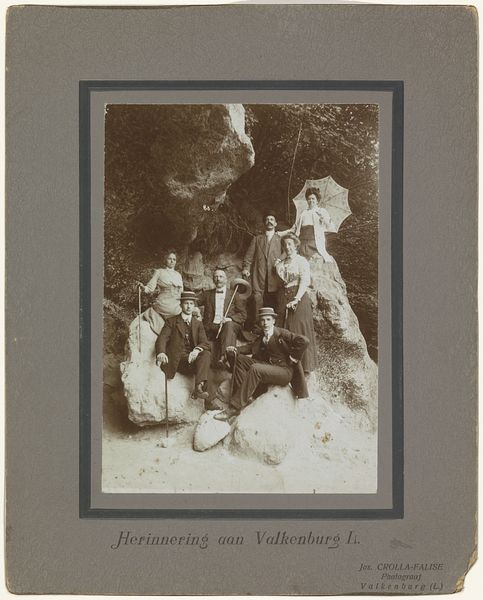

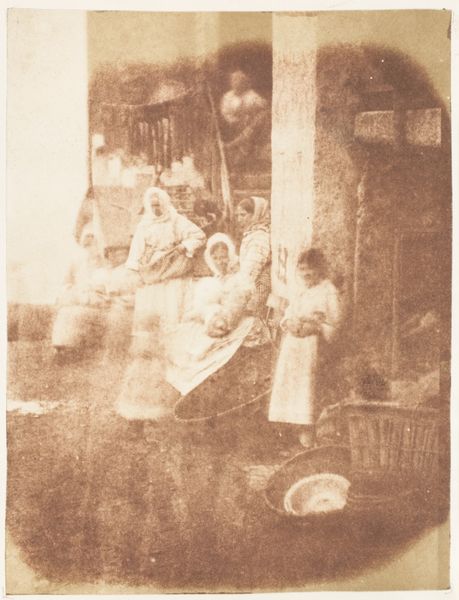

Curator: What a compelling gelatin-silver print. This photograph by Louis-Pierre-Théophile Dubois de Nehaut, dating from around 1854-1856, is titled "Jardin zoologique de Bruxelles; Les trois jumeaux fils de Mr. Lebens et toute la famille." It resides here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: There's an incredible stillness to it. A staged tableau. The faces are blurred, ghostly almost, and it feels like peeking into a forgotten moment in time. The processing looks uneven. Curator: The setting in the Jardin Zoologique is critical, wouldn't you agree? Zoos were becoming incredibly popular during this period. Photography was still novel; combining the two offers a powerful insight into 19th-century social rituals. Families publicly showcasing their wealth and status amid controlled wilderness. Editor: Absolutely. And note the presence of what looks like a large dog or maybe even a small pony in the shadows; its role in the tableau as an interesting display of animal domestication. It is, itself, like another prop brought in, along with this impressive wheeled chair in which a couple of the family members seem seated. Curator: Consider the material conditions required for such an image. The specialized labor to make such large-scale, well-equipped urban recreational centers accessible and popular, the industrial processes to provide adequate technology in photography. Here the artist captures a slice of that history in one frame, literally and figuratively. Editor: I'm struck by the tension between the Romantic backdrop of a "natural" setting, a city zoo landscape that almost mimics a stage, and the deliberate posing of the family. They aren’t interacting with their environment. This wasn't about spontaneous documentation. This speaks to rigid societal roles and performances within the upper middle class. The photographic equipment also helped shape artistic vision and perception and created certain aesthetic boundaries of that time. Curator: Exactly. Think about how these early photographic processes also informed painting. Consider also, from an art market standpoint, the creation of value through portraits during this period. This type of documentation legitimized the status of upper-class subjects and perpetuated certain historical perspectives. Editor: Seeing it through a lens that focuses on production and class helps one decode many aesthetic, historic and social elements simultaneously. The history is materialized in this gelatin silver print, making this an excellent contribution to a wide conversation that needs to happen when we look at 19th-century art and photography. Curator: Agreed, a fascinating snapshot into a layered past, accessible through a combination of visual assessment and historical digging.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.