Copyright: Public Domain

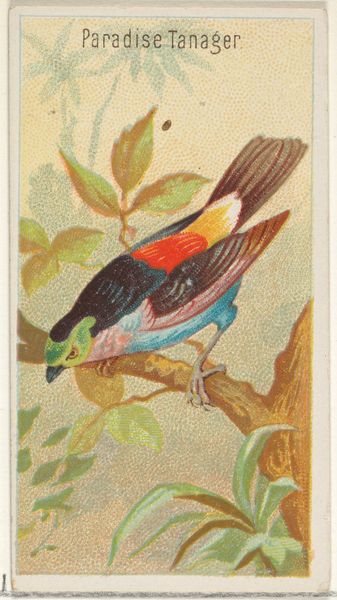

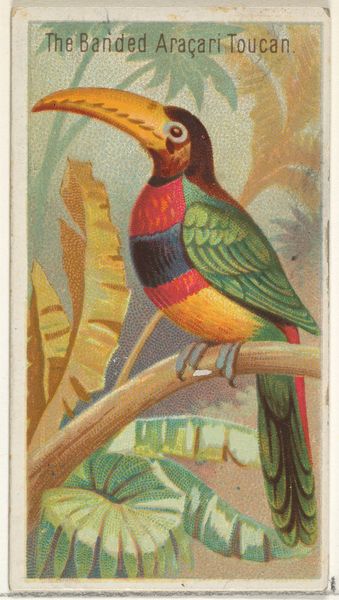

Curator: I'm struck by the dramatic contrast of colours. The vibrant plumage set against the pale leaves creates an almost theatrical feel. Editor: Precisely. This is “Plate 17,” a watercolor print by William Matthew Hart, made sometime between 1875 and 1888. Hart worked at a time when illustrated natural history books were vital to the expansion of European scientific knowledge. These artworks served to catalogue species while shaping Western perceptions of the non-European world. Curator: So, not simply an objective record, but actively constructing an idea of nature? I see it. There is something staged about the presentation. Look how the artist directs our gaze – the intense details in the bird's feathers that direct our eye, then to the contrasting simplicity of the branch and leaves. Editor: These images often reinforced a hierarchical view of the world, and in many cases served imperial interests. The exotic appeal of a species like this Bird of Paradise contributed to narratives of the 'untamed' or the 'primitive' lands from which they originate, justifying intervention and exploitation. Curator: So it's a piece that reveals how scientific illustration participated in complex political agendas. I do still appreciate the intense visual focus of Hart here. He so clearly loved to draw those feathers. The details—such care, line by line—suggest hours of direct observation. Editor: It does demonstrate his craftsmanship, and reflects a trend toward increased visual accuracy. Artists and publishers gained notoriety and influence in popular science circles with the expansion of printing and increased literacy. Curator: Knowing this background enriches my viewing experience immensely. Editor: Agreed. Examining this piece, from both the perspective of its visual language and its role in shaping colonial-era ideologies, encourages a more holistic understanding of art history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.