drawing, pencil

#

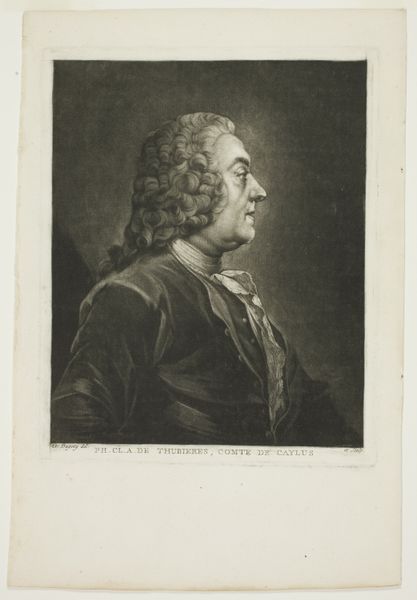

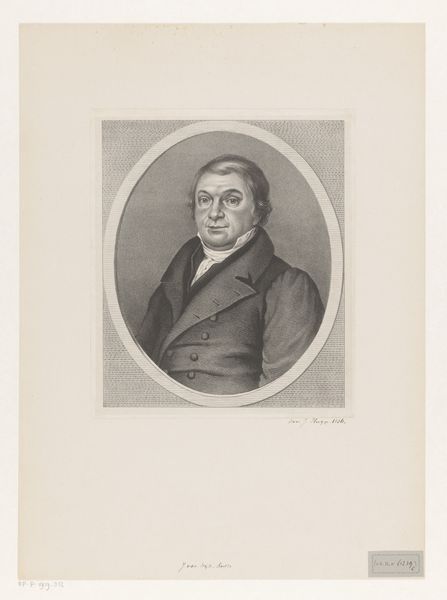

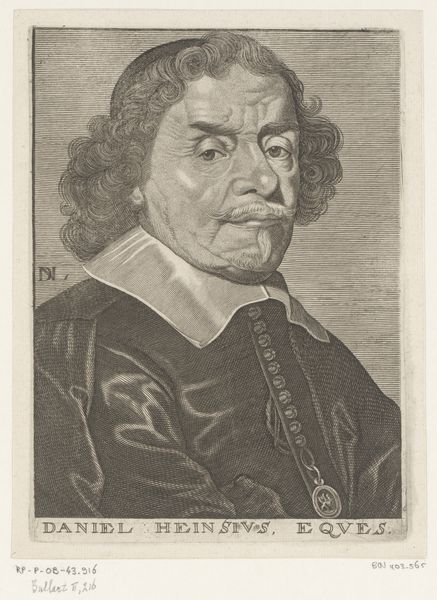

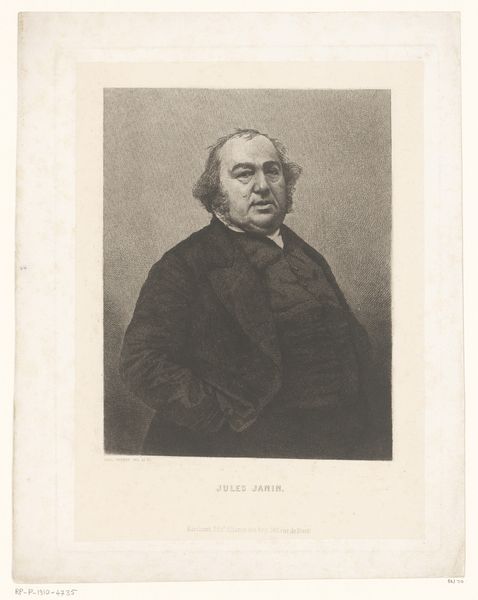

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

facial expression drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

caricature

#

portrait reference

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

animal drawing portrait

#

portrait drawing

#

portrait art

#

fine art portrait

#

realism

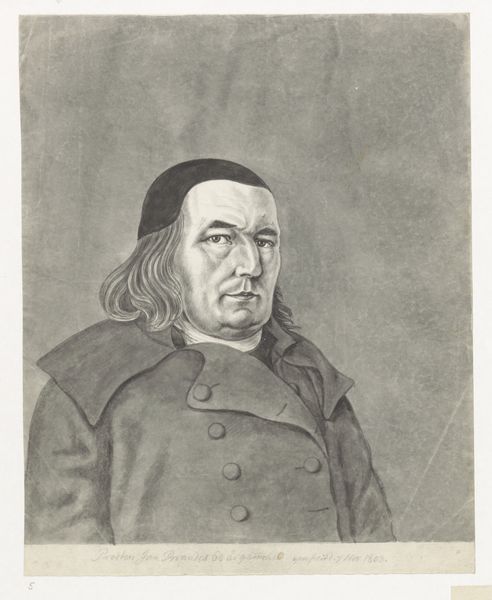

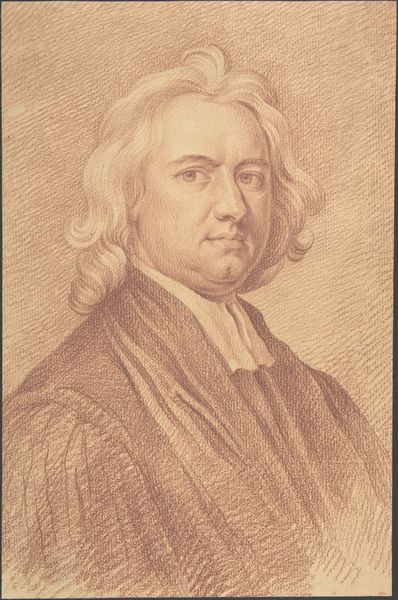

Dimensions: height 203 mm, width 161 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

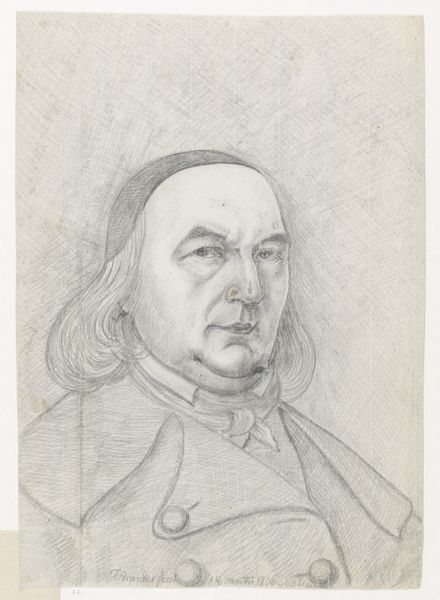

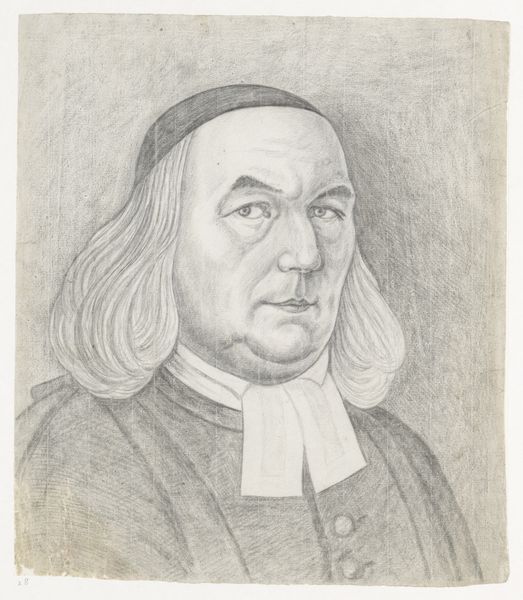

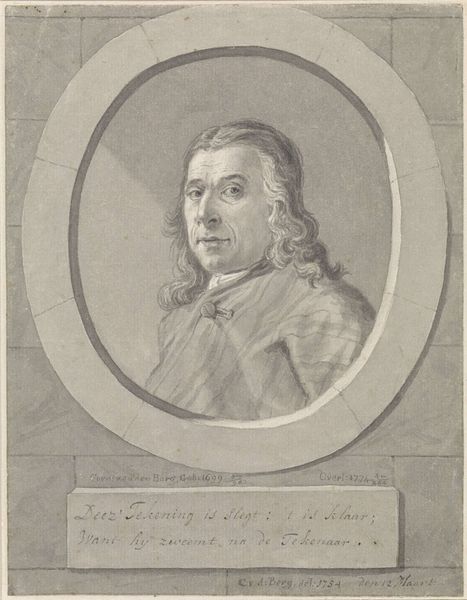

Curator: Here we have a self-portrait by Jan Brandes, created sometime between 1803 and 1811. It's a pencil drawing, possessing an air of directness, wouldn't you agree? Editor: Yes, immediately striking. There's a subtle tension. His gaze is rather unnerving, almost accusatory. It begs the question, what historical conditions informed the mood we see rendered in the face? Curator: Brandes lived through the Batavian Republic, a period of revolutionary and Napoleonic influence. The Dutch East India Company was collapsing; an old order was crumbling. This self-portrait, in its somewhat stark realism, becomes a symbol of self-reflection amidst societal upheaval. The lines, while soft, possess a precision that evokes this era of both reflection and social agitation. Editor: Precisely! And look at the clothing. The seriousness in his clothing signals social anxieties around representation and status during a period of significant cultural transition. His simple cap and rather modest coat are a clear signal for his class or social role during the time. It resists any romanticism or attempts at the lavish depiction favored previously by those in power. Curator: Furthermore, the artistic simplicity—the pencil as opposed to more luxurious paints—speaks volumes. Think about what it means to choose a simple medium for self-representation when options may be restricted. This creates more powerful intimacy. There is also an intense humanity revealed, despite whatever limitations existed for him during that time period. Editor: Indeed. The very act of creating a self-portrait suggests an assertion of agency, but a subdued one that signals a resistance within constrained boundaries. How, then, did such visual choices impact contemporary audiences, and how are they relevant today regarding similar situations when power is being struggled for. Curator: I think that by stripping away pretense, Brandes connects to us across centuries, encouraging a powerful mirroring—his reflection, ours. The work becomes a lens. Editor: Right, and we, as viewers, are implicated in the reflection, asked to consider our role in constructing—and contesting—dominant narratives. A pencil drawing from 1803 can have as much subversive power now as it did then.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.