photography

#

pictorialism

#

landscape

#

photography

#

monochrome

Dimensions: height 78 mm, width 110 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

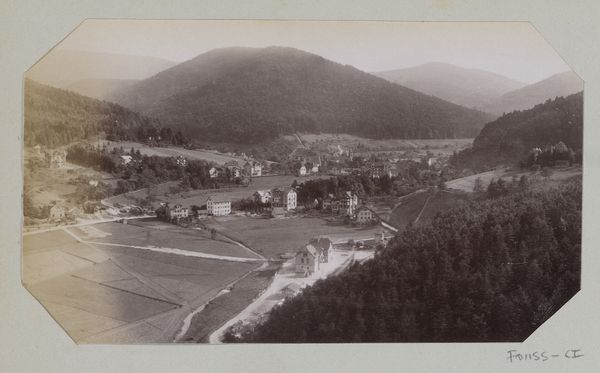

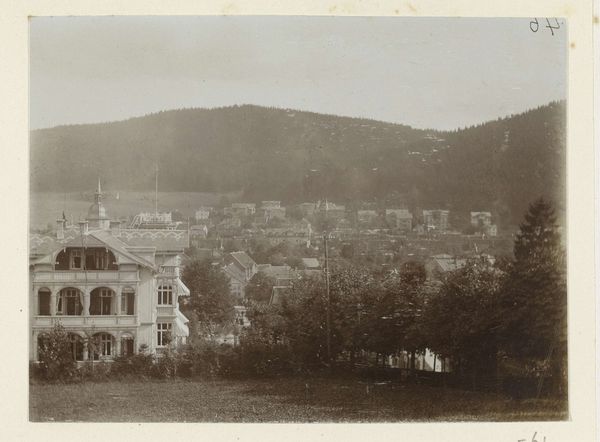

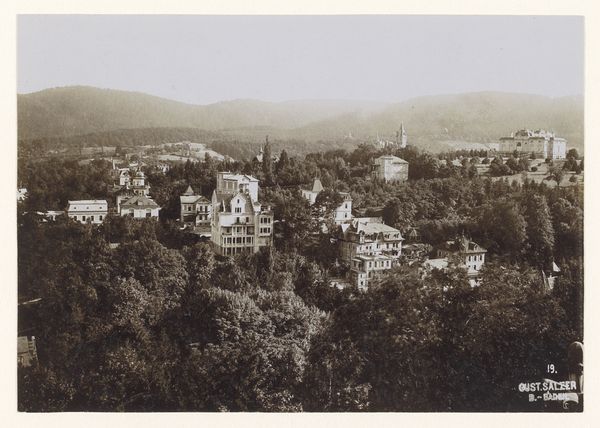

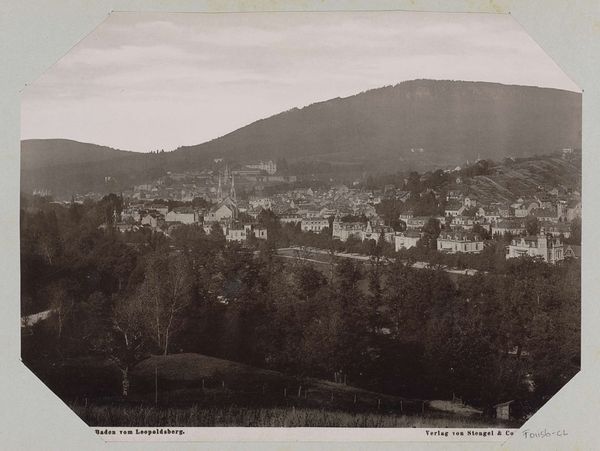

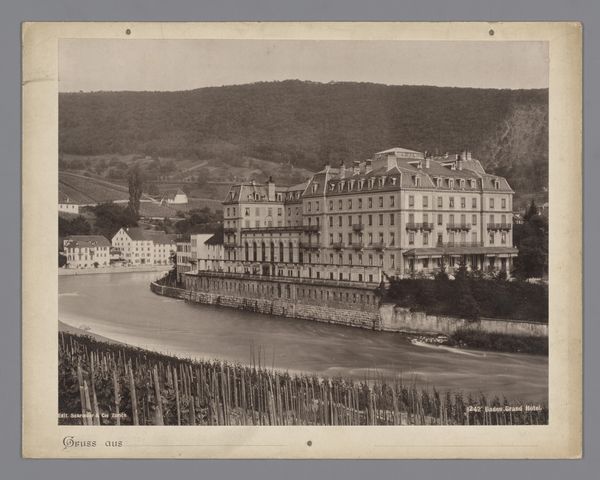

Curator: Looking at this work, "View of the Church Village of Valbert and Surrounding Hills," a photograph dating roughly from 1890 to 1910, one is struck by the clear attempt to capture a specific place and time. Editor: Yes, my immediate reaction is one of quietude, almost melancholy. The monochrome tones lend a certain somber quality, and the composition, the way the village is nestled in the valley, conveys isolation. Curator: This aligns with the period, and it is worth considering the broader social context. Landscape photography during this era often reflected the growing romanticism of rural life, but also a changing relationship with industrialization. The flight to the countryside that accompanied industrialisation changed villages irrevocably, with modern builds being incongruously grafted to established architecture. Editor: From a formal perspective, the photographer uses strong horizontal lines – the ridge of the hills, the line of the buildings – to create a sense of stability, of groundedness. There’s also a subtle interplay of textures: the soft blur of the distant hills against the sharper focus of the village. Curator: Precisely. Consider how photography began influencing ideas around urban versus rural ideals in Germany. Before the 20th century the distinction was less well defined: here the separation and hierarchy are clearly presented as self-evident fact. Editor: It's interesting how the pictorialist style contributes to this. The slightly soft focus, the manipulation of tones, all serve to enhance the sense of a nostalgic past. The landscape almost reads as idyllic—a contrast with the rapidly industrializing world. Curator: The camera wasn’t a neutral recorder of information; the photographer clearly curated a narrative to emphasise a view. Photography played a key role in reinforcing nationalist sentiment by shaping perceptions of land, community and history. It defined culture through representation. Editor: I appreciate how our readings can converge through different lenses. My feeling is one of peace, but it becomes evident there is also subtle control being enacted within what I would describe as the framing device— the photograph's border defining place and time, an early study on the politics of perspective. Curator: It allows us to explore the complex interplay between art and societal context, in turn helping to reveal ways of understanding power relations within early twentieth-century society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.