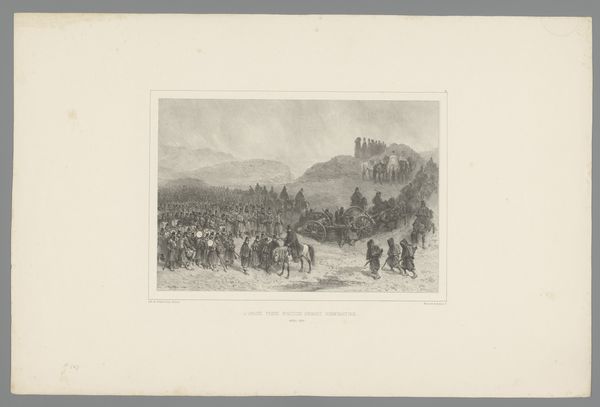

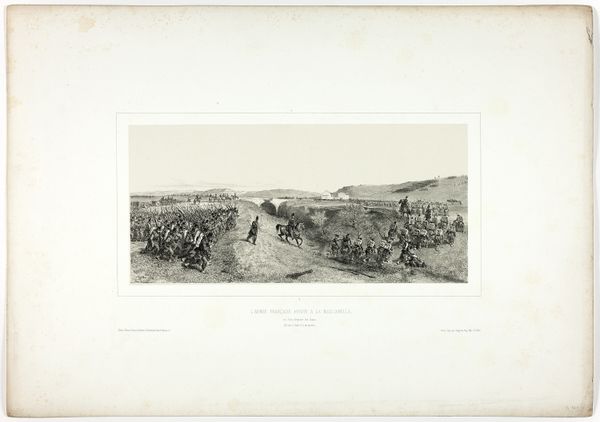

Soldaten te voet, te paard en per kar onderweg naar Constantine, oktober 1837 1838

0:00

0:00

augusteraffet

Rijksmuseum

drawing, lithograph, print

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

lithograph

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

watercolour illustration

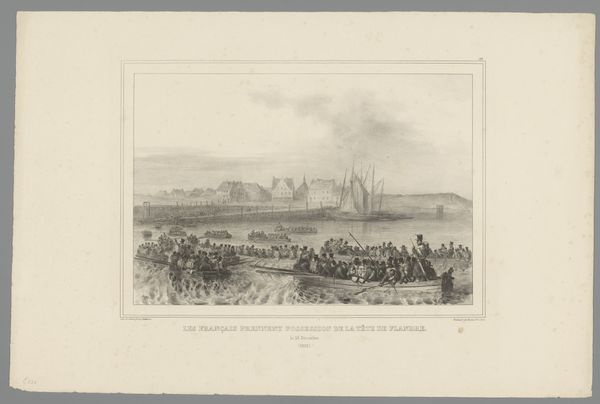

Dimensions: height 364 mm, width 550 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

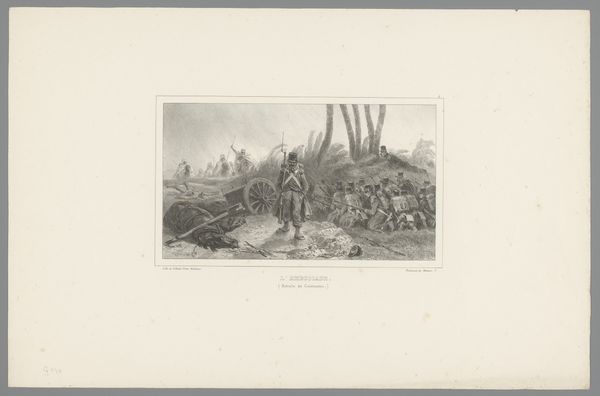

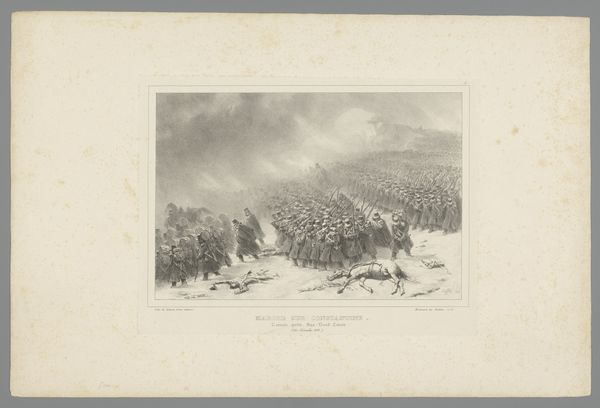

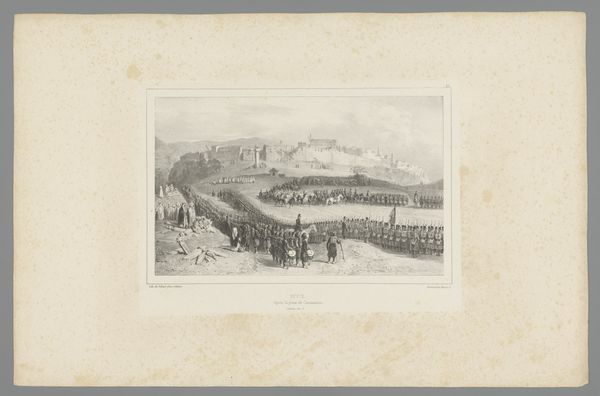

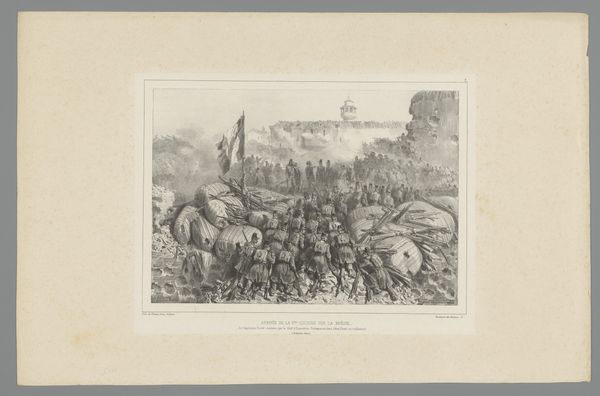

Curator: Looking at this detailed lithograph by Auguste Raffet, created in 1838, the eye is immediately drawn to the landscape filled with figures entitled "Soldaten te voet, te paard en per kar onderweg naar Constantine, oktober 1837". What's your first impression? Editor: Bleak, immediately. The monochrome palette contributes to this, along with the sheer number of individuals depicted on what appears to be a very barren landscape. There is a sense of forced movement and, dare I say, exhaustion communicated through the image’s materiality and process. Curator: Indeed. The title gives us a clue as to what's happening: soldiers are making their way to Constantine, now Algeria, in October of 1837. Raffet, deeply affected by the Napoleonic campaigns, imbued this work with socio-political meaning. The lithograph serves as a glimpse into France's colonial past. Editor: The colonial project is made up of labor, logistics, and above all the supply of resources. When I look at this print, I consider the logistics needed to support such an operation. What type of ink did Raffet use to capture the scene, and where was it produced? And more importantly, under what socio-economic conditions did its production happen? Curator: I am in alignment with the socio-economic circumstances that permitted France's expansion across North Africa. When studying such pieces it is paramount to understand who profited and who was damaged. Editor: I agree completely. And if we closely inspect the forms, notice how Raffet is able to render depth through varied marks. But also take into consideration how industrial processes democratized and proliferated such images across Europe. These mass produced prints had tremendous ideological value. Curator: Yes, the reproducibility is definitely central to the artwork. This imagery permeated 19th-century French culture, influencing views of the military. Ultimately, Raffet's choices force us to ask complex questions about war, colonialism, and representation. Editor: Exactly, and it compels us to analyze what materials were used and under what conditions to render this image of war for widespread consumption. The means of production deeply informed its meaning. Curator: In sum, seeing it today allows a window into how warfare was visually constructed and socially understood in that era, which is invaluable from both aesthetic and historical viewpoints. Editor: For me, it provokes me to reconsider how art production mirrors broader material conditions, which in this case serves as a visual bridge that links aesthetics to tangible history and economics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.