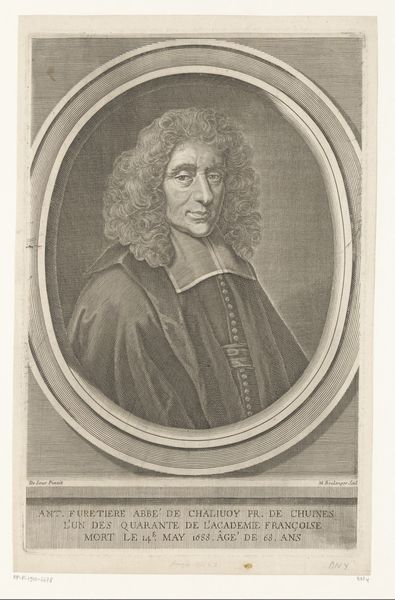

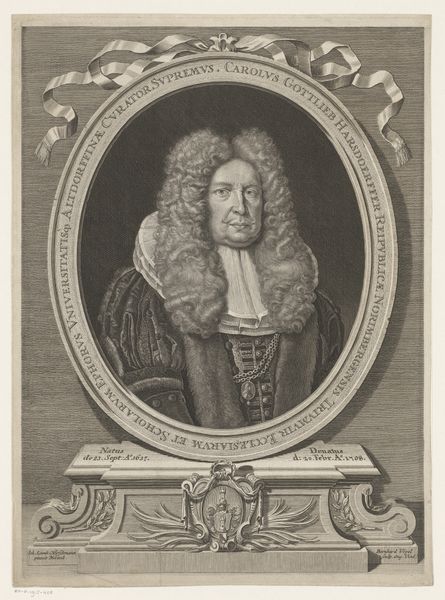

engraving

#

baroque

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 405 mm, width 337 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have "Portret van Pierre Daniel Huet," an engraving made sometime between 1730 and 1750 by Louis Moreau. It’s a pretty formal portrait. I am interested in what a Materialist might focus on. What elements stand out to you in this work? Curator: This engraving provides a wealth of information when considering it from a Materialist perspective. I am particularly interested in the social and economic context that made such a portrait possible. Engravings like this were not mere decorations, they served a function within the economy of image production. Editor: Function, as in, were they mass-produced? Curator: Precisely. Engravings allowed for relatively widespread dissemination of an image. We must consider the engraver, Moreau, as a craftsman within a system of patronage and demand. The portrait celebrates Bishop Huet, embedding his image into circulation. But who commissioned this? Who bought it? What was the labor involved, the paper, the ink? The choice of engraving as a medium, indicates that distribution and availability were primary concerns. It makes me wonder about the intention of production and how it ties into larger issues of class and religion. Editor: I see what you mean. So the "how" and "why" it was made reveals a lot about the society. Curator: Exactly. Considering the materials, labor, and intended consumption provides us with a tangible connection to the social conditions of its creation. It urges us to move beyond seeing it as simply an aesthetic object, but instead as a historical artifact embedded within networks of power and exchange. Editor: Thanks. Thinking about the labour and access has made me reconsider the power this portrait conveyed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.