photography

portrait

black and white photography

street-photography

photography

black and white

monochrome photography

monochrome

realism

monochrome

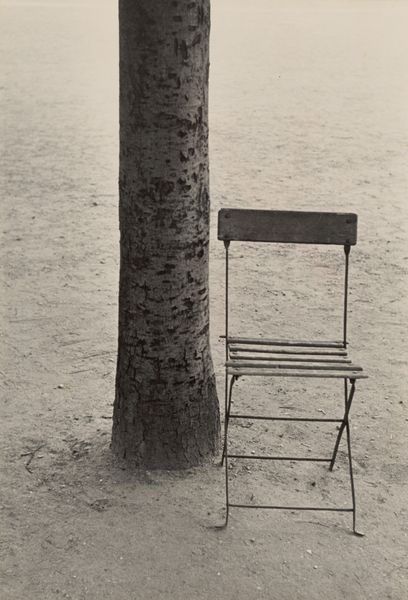

Dimensions: image: 38.5 × 38 cm (15 3/16 × 14 15/16 in.) sheet: 50.17 × 40.32 cm (19 3/4 × 15 7/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

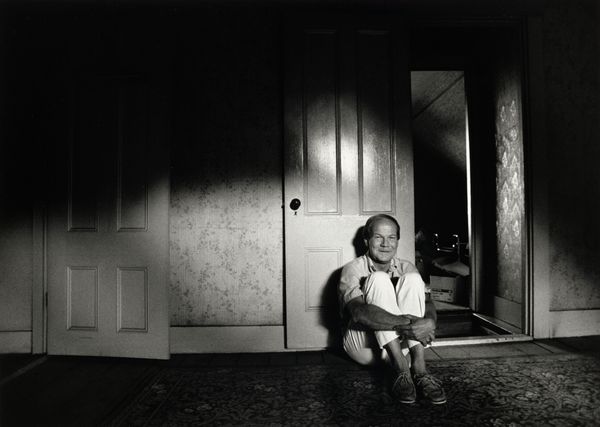

Curator: Arthur Tress captured this stark, affecting photograph, "Last Portrait of My Father, New York City," in 1978. The work uses black and white photography and provides an introspective portrayal. Editor: There's a profound sense of melancholy in this image. The monochrome palette amplifies the feeling of isolation. A man sits alone in the snow, seemingly vulnerable yet regal atop that elaborate chair. Curator: Let’s contextualize Tress's work. His images often explore themes of identity and mortality. Here, we see a focus on the patriarchal figure at the close of his life, potentially reflecting anxieties about aging and societal roles in the late 20th century. How does that reading impact you? Editor: It deepens the layers. That wrought iron chair resembles a throne, evoking both authority and confinement. It could symbolize inherited power, the weight of expectations… But placed outdoors, in winter, all those symbols of dominance seem diminished, fragile, human. Curator: Absolutely, it highlights how such figures often uphold capitalist power structures. A close reading will indicate that late capitalism strips everyone of meaning, irrespective of position. How else do you see Tress employing symbols? Editor: The snow itself feels significant. In many cultures, snow symbolizes purification, or even oblivion. Covering everything, it nearly obliterates the background, turning the landscape into an empty, blank space surrounding the father figure, symbolizing his exit from life. I wonder about Tress’s emotions in memorializing this scene. Curator: It resonates, I think, with many families facing generational shifts and the struggle for meaningful connection within evolving social dynamics. The work is an introspective case study in hegemonic power struggles and societal changes reflected on the individual, but also representative for society. Editor: It all brings me back to the image's quiet sorrow, resonating beyond personal history into something universally human. Curator: Yes, situating his image in its historical and theoretical setting really deepens our understanding of the family, the father, and his work in social history. Editor: It transforms the personal into something archetypal.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.