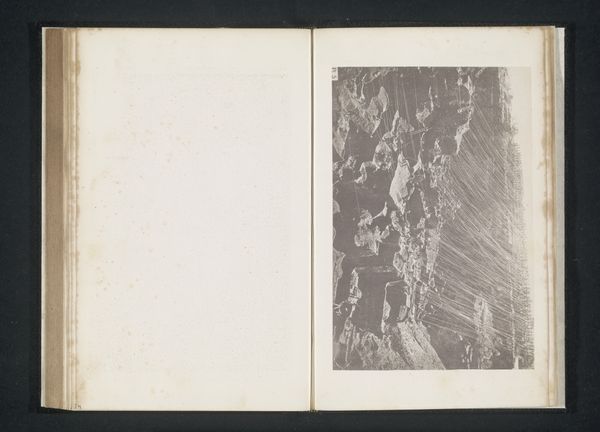

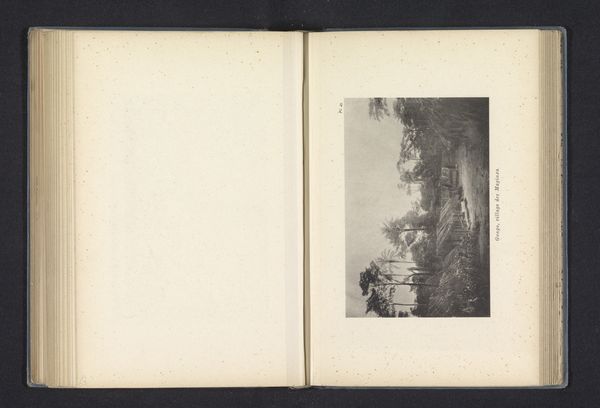

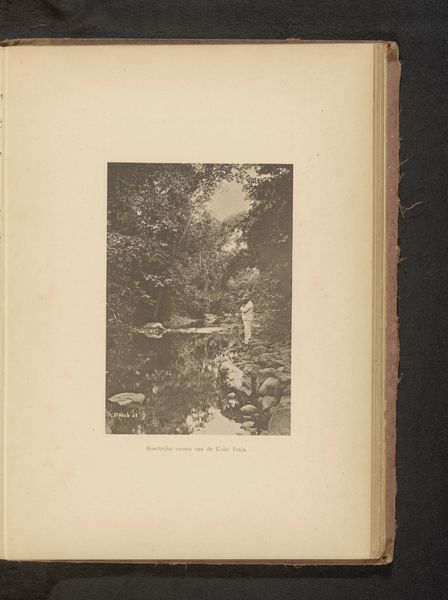

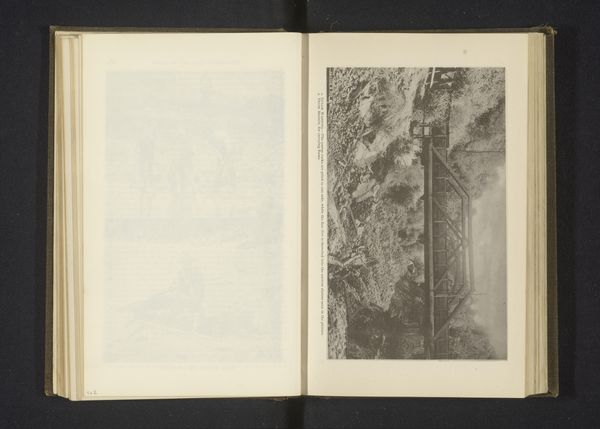

Gezicht op een diamantmijn in Zuid-Afrika, vermoedelijk bij Kimberley before 1880

0:00

0:00

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 125 mm, width 192 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What a stark image. There's something incredibly daunting about the sheer scale of this man-made gorge. Editor: Indeed. What we’re seeing here is a gelatin-silver print, thought to be captured before 1880 by the Gray Brothers. Its title rather plainly describes "Gezicht op een diamantmijn in Zuid-Afrika, vermoedelijk bij Kimberley" or, in English, "View of a diamond mine in South Africa, presumably near Kimberley." Curator: The word 'mine' immediately activates an association for me: ideas of wealth and also images of grueling labor, but I think its black-and-white tonality only amplifies the feelings of extraction, both material and human. Editor: Absolutely. The print appears to show the beginnings of extreme wealth derived from extreme methods. It is presented in the visual style of Realism, which in its early photographic application showed all the blemishes that industrial expansion was making on society. Consider what these spaces represent, and who would or would not be able to possess them. Curator: What do you think it might signify? Looking at it, I see more than an environmental cost. It almost appears like an ancient ziggurat or a crumbling, forgotten temple. Could the diamond itself have held a different kind of symbolic weight before the diamond rush changed everything? A weight now eroded like the rock. Editor: That's a provocative reading. You're making me reconsider this in terms of psychological as well as historical displacement. How the physical environment changes so abruptly mirrors equally brutal disruptions to traditional societal power structures. Diamonds as the totems of progress. Curator: Exactly. These are places where power and capital get completely redistributed - it almost serves as an idol, one where you can see both immense wealth as well as extreme violence in labor that leads to it. The mine itself starts functioning like this physical representation of all this history, emotion and belief! Editor: It speaks to the seductive nature of wealth. This single image encapsulates a significant moment in South Africa's socio-economic transformation under Imperial influence. Before the rise of museums or public interest groups, photography helped build knowledge about lands outside Europe that the public consumed with enthusiasm, sometimes at the expense of their own. Curator: Yes, this is no mere landscape. Thank you, I see new layers of implications here now that perhaps weren’t so apparent at first. Editor: Thank you, too. Thinking about art as objects of cultural memory enriches their ability to reveal their significance to visitors.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.