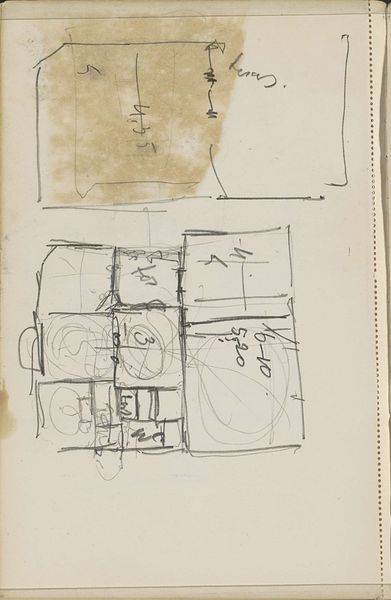

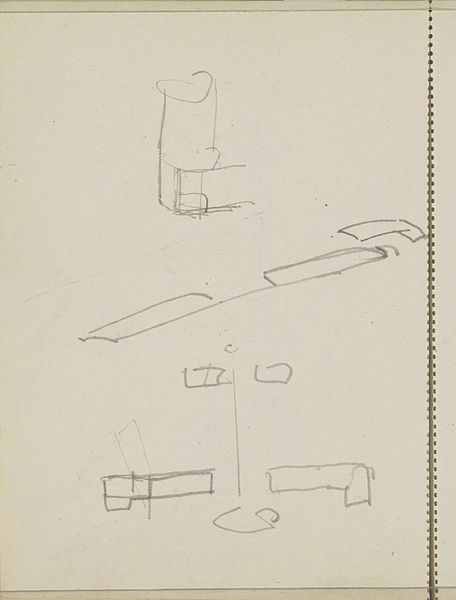

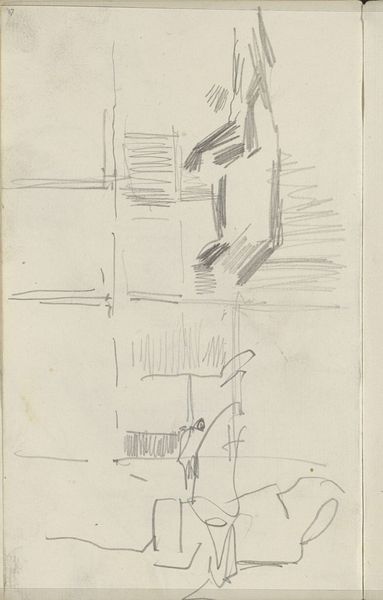

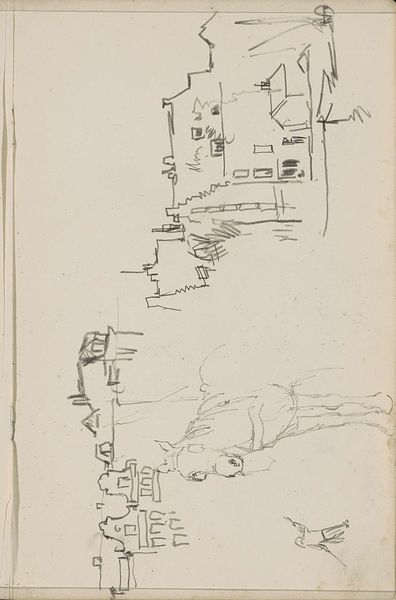

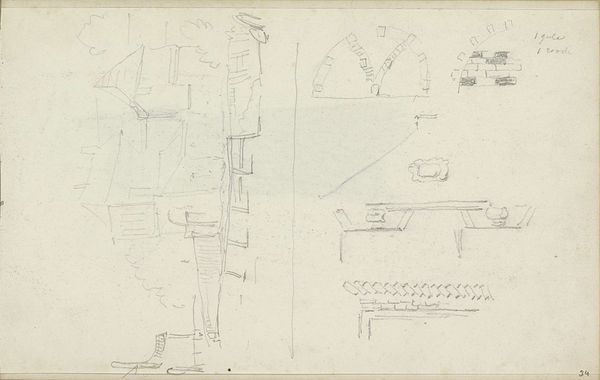

Vooraanzicht en plattegrond van een vrijstaand huis 1890 - 1946

0:00

0:00

cornelisvreedenburgh

Rijksmuseum

drawing, paper, pencil, architecture

#

drawing

#

paper

#

form

#

geometric

#

pencil

#

line

#

cityscape

#

architecture

#

building

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What strikes me immediately about this pencil drawing on paper is its deliberate incompleteness. The sketch of a freestanding house presents not a finished architectural rendering but a kind of diagram. Editor: Indeed. The Rijksmuseum holds this intriguing work by Cornelis Vreedenburgh, titled "Vooraanzicht en plattegrond van een vrijstaand huis" or "Front view and floor plan of a detached house," dated sometime between 1890 and 1946. It feels utilitarian, stripped down. Curator: Utilitarian, yes, but also conceptually rich. The composition itself draws attention to the line. The lines aren’t striving for realism; they’re exploring the essential form. There’s a tension between representation and pure abstraction. Look at how the ground floor plan is seemingly disassembled. Editor: As a historian, I can’t help but consider the context in which Vreedenburgh was working. This period saw immense changes in urban planning and social housing. Could this drawing be interpreted as a response to those shifts, a kind of democratization of design where even a modest dwelling receives careful consideration? What are we, as a society, conveying through architecture and how is it reaching people? Curator: It certainly provokes questions. It may allude to an awareness of geometric forms and spatial arrangements that go beyond simple functionality. Take the facade, a sequence of square-ish forms in seemingly rhythmic articulation. There is perhaps the intent here of transforming architectural language into a visual or textual poetics. Editor: And perhaps that points to a tension—between the personal space represented and the wider public space which it serves. Is he subtly questioning who gets to define 'home,' who designs these spaces and who is designing to inhabit them? What social ideas are coded into the buildings? Curator: Perhaps it is not in offering solutions but revealing complex, spatial negotiations to be had. A kind of structural invitation. Editor: Exactly. It highlights the political importance of everyday forms of dwellings. And reminds us that, like architecture itself, artistic and historical interpretation requires layering, planning, and multiple perspectives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.