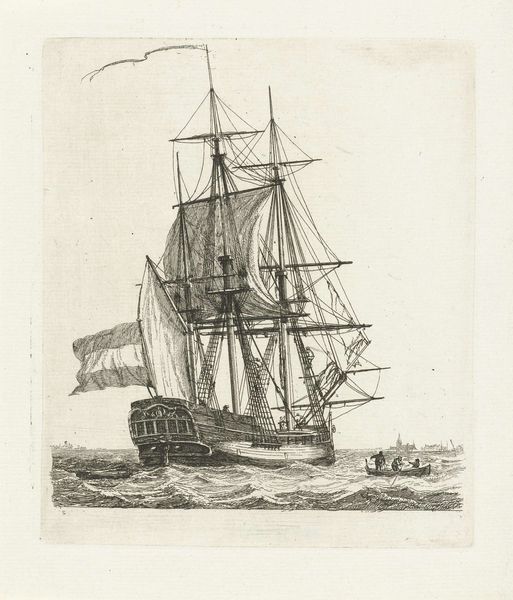

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

landscape

#

line

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 128 mm, width 154 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

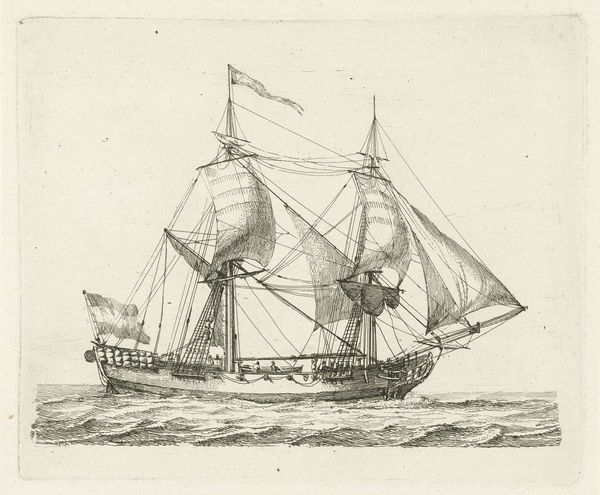

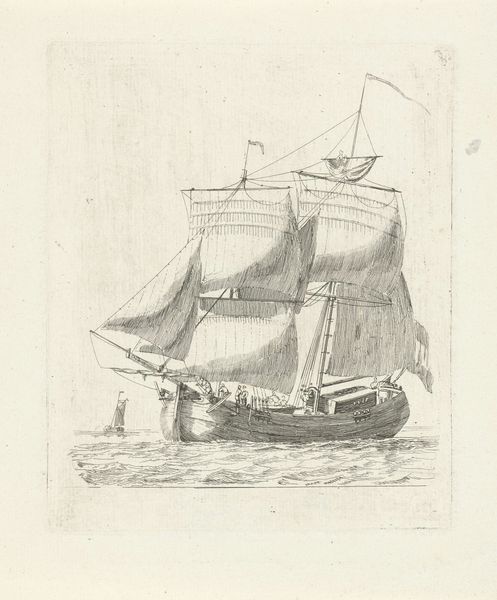

Curator: Here we have Gerrit Groenewegen's 1789 engraving, "Tweemaster met vlag en figuren," or "Two-Master with Flag and Figures," a study of a Dutch ship rendered with astonishing precision. Editor: It’s fascinating—a study in shades of gray. Immediately, I see a dynamic tension between the static ship and the suggestion of movement through the wind in the sails and waves below. The textures created with engraving lines make the boat stand out from the light backdrop, with so much work etched for depth in each part of the composition, from the rough seas to the complex ship rigging. Curator: Indeed. This engraving depicts more than just a ship; it is imbued with symbolic significance of Dutch maritime power and exploration during the Golden Age, wouldn’t you agree? It represents an entire narrative of trade routes, naval strength, and cultural exchange across oceans. Editor: I’d argue that this print reveals just how intensive printmaking was at that time. You can imagine Groenewegen meticulously etching those lines into the plate, spending hours carefully developing this single image. Printmaking's a powerful tool for disseminating information – a much more efficient way of spreading iconography in the eighteenth century than oil paint, for sure. And to consider who then consumes these prints is revealing. Curator: Exactly! And note how the details serve specific iconographic functions. For example, the flag isn't merely a national symbol, but an emblem of national pride and power and independence for a young, rising commercial society, even then. Look also to the barely visible figures on the deck, representative of countless stories from across continents that the ship touched. Editor: What do you make of the fact that this is an engraving, a repeatable image? I think we need to look into whose homes this print wound up in, who consumed the images of sea-faring vessels, and what social networks they engaged with. What was the labor involved and who consumed this vision of naval conquest, in 1789? This is pre-photography; in what ways were the Dutch consuming images and projecting social class and fantasies via these prints? Curator: These questions definitely lead us to deeper understanding. The ship then serves as an enduring symbol – in its detail and material form -- representing national ethos. Editor: Ultimately, though the Dutch Golden Age gets viewed now with the patina of classic high culture, works like this also remind us to reflect critically on the intense physical labor of maritime ventures and the circulation of associated imagery. The means of production can shed some critical insights onto social imaginaries!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.