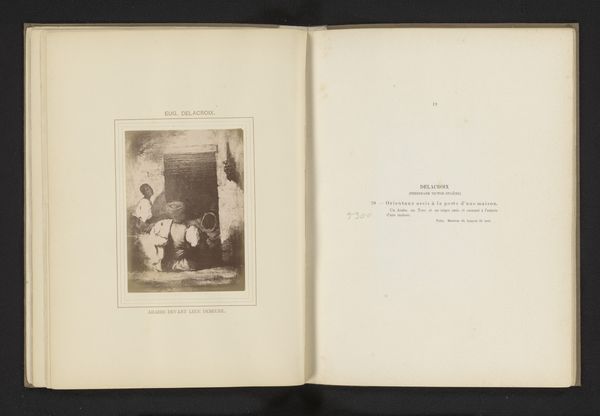

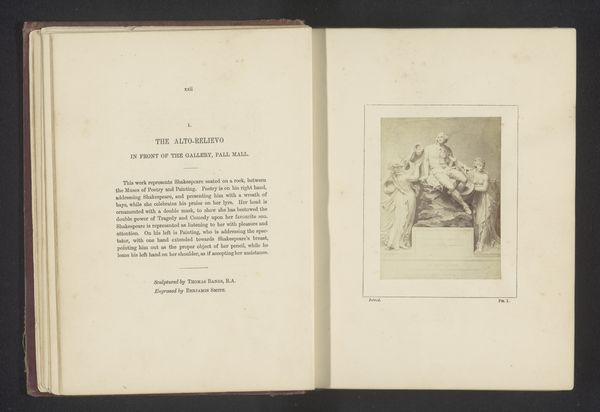

print, paper, photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

aged paper

#

homemade paper

#

paper non-digital material

#

paperlike

# print

#

sketch book

#

paper texture

#

paper

#

photography

#

personal sketchbook

#

journal

#

fading type

#

thick font

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 215 mm, width 163 mm, thickness 15 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have an albumen print from 1871 entitled "The Birth and Childhood of Our Lord Jesus Christ," attributed to diverse producers. I’m struck by how intimate it feels, like stumbling upon a personal sketchbook. How do you interpret this work? Curator: I see this piece as a fascinating intersection of faith, reproduction technology, and social aspiration in the Victorian era. The use of albumen print, a relatively new photographic process at the time, to disseminate religious iconography speaks volumes about the democratization of art and religion. This wasn't a fresco in a cathedral only accessible to the wealthy; this image, reproduced through photography, could be owned and contemplated in the domestic sphere, ostensibly available to a broader spectrum of society, albeit within a clear class structure. Editor: So, the medium itself carries a message of accessibility? Curator: Precisely. And we must also consider who *gets* access and how the printing technology, while progressive, does not overcome deeply ingrained barriers. Think about the colonial project running parallel at this moment in history; how are such images distributed, and to whom, outside of the West? Is this birth narrative presented as universal, and what cultural norms are being erased or undermined as a result? It also leads me to wonder about the power dynamics inherent in the act of ‘meditating’ upon these images, carefully chosen to reflect and perhaps reinforce very specific notions of Victorian piety and family values. Editor: That really changes how I see the piece. It’s not just a devotional image; it's a carrier of cultural and maybe even colonial ideologies. Curator: Exactly. It reminds us that even the seemingly benign and universally appealing images are always embedded within networks of power, representation, and social control. Thinking about art from this perspective allows us to excavate these submerged narratives. Editor: I’ll never look at religious art the same way again! There is definitely much more beneath the surface.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.