daguerreotype, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

historical fashion

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

#

genre-painting

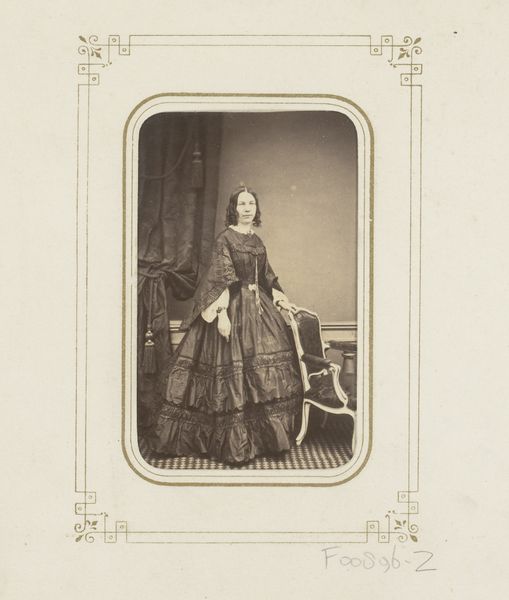

Dimensions: height 99 mm, width 62 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this gelatin-silver print, "Portret van een vrouw bij een spiegel," made between 1865 and 1871 by Maull & Polyblank... there's a certain solemnity to it, a quiet elegance. How do you interpret this work in the context of its time? Curator: The seriousness you observe likely stems from the conventions of 19th-century portraiture. Photography was becoming increasingly accessible, but it still carried a weight, a sense of capturing posterity. The subject's dress, that elaborate full skirt and restrained bodice, signals her social standing. It speaks volumes about the role of women in Victorian society – their lives often defined by strict codes of conduct and presentation. Editor: That's a good point about the conventions. Did the rise of photography influence painting or other art forms at the time? Curator: Absolutely. The democratization of image-making pushed painters to explore new artistic territories. Think about the Impressionists who emerged in the late 19th century. They focused on capturing fleeting moments and subjective experiences, things photography couldn't easily replicate then. The photograph created new avenues of art as it eliminated others. The mirror and how it related to the status of women as the 'decoration' to be mirrored becomes prevalent, and the photograph captured a truth more intimate. Editor: I hadn’t considered how photographic advancements spurred artistic movements. It’s fascinating how socio-political and technological forces shape art. Curator: Exactly! And remember, photographs aren’t neutral records. Consider the studio setting, the photographer’s choices about lighting and pose – these are all carefully constructed to project a certain image, both literally and figuratively, of the subject and the era. Editor: Thank you, that sheds new light on historical portraiture for me. I'll definitely think about the socio-political context of images more deeply from now on.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.