Dimensions: height 87 mm, width 60 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

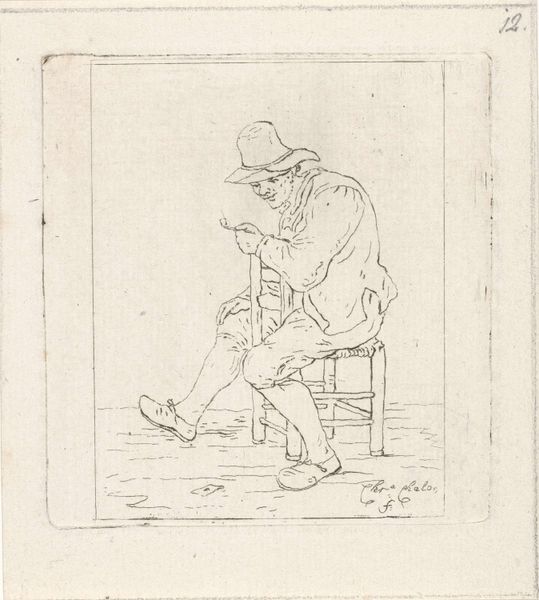

Curator: This is Johannes Adrianus Schultz’s etching, "Drinker," likely created sometime between 1830 and 1863. The artwork presents a jovial figure, casually seated with a glass in hand. What strikes you first about this image? Editor: The first thing that grabs me is the air of unapologetic leisure. He's comfortable, almost performatively so, and I can’t help but wonder about the societal norms that permit such public displays of enjoyment, and for whom. Curator: Indeed, Schultz seems to be capturing a specific character, a genre-painting trope almost, one that reverberates through Dutch Golden Age paintings and beyond. The drinking man, as a symbol, tells tales of merriment, excess, sometimes even moral decline. The etching technique itself lends a sense of historical echo, doesn’t it? Editor: Absolutely. Etching brings to mind ideas around authorship and circulation of imagery, speaking to class and access to culture. How does the symbolism connect to issues of identity or societal structures present at the time the print was created? I’m thinking particularly about the intersection of leisure, labor, and social status. Curator: He's certainly no peasant, judging by the flamboyant hat and cavalier boots. He's perhaps a burgher, a figure positioned comfortably within the burgeoning merchant class of the era. The glass, held aloft, could symbolize prosperity, an enjoyment of newfound economic freedoms. It’s like a self-assured character that claims to have the right to these freedoms. Editor: Yes, I see the subtle swagger there, but I’m also considering what that performance obscures. Whose labor affords him that drink? Whose exclusion underpins his status? There’s an argument to be made here about historical power structures made subtle. Curator: A vital question, really, about seeing what the visual text both shows and perhaps hides. But what endures, for me, is that core image, that almost archetypal depiction of someone claiming—visually at least—their place within society's pleasures. Editor: And questioning that claim and its impact remains deeply relevant today. That's the power of historical dialogue, isn’t it? Curator: It is indeed. A continual process of reading and rereading visual culture in the hopes of progress and equity.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.