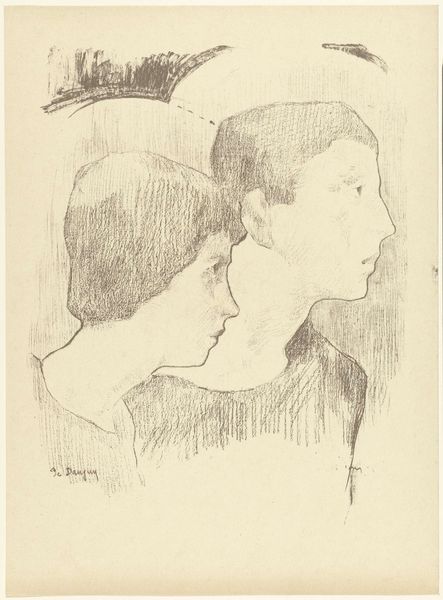

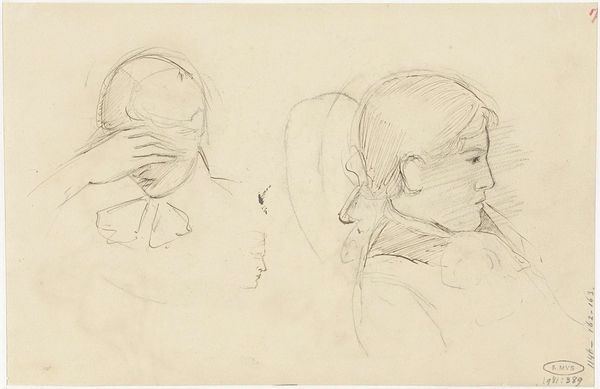

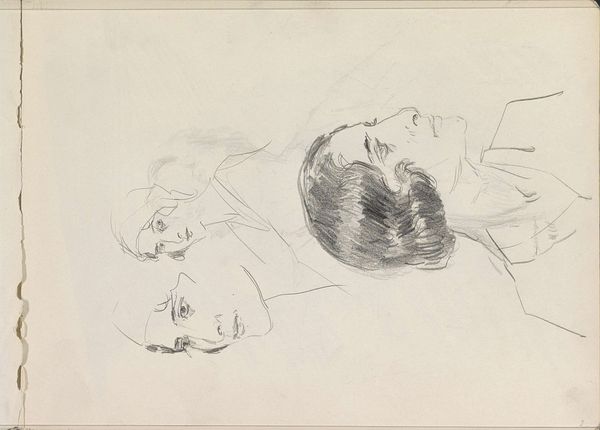

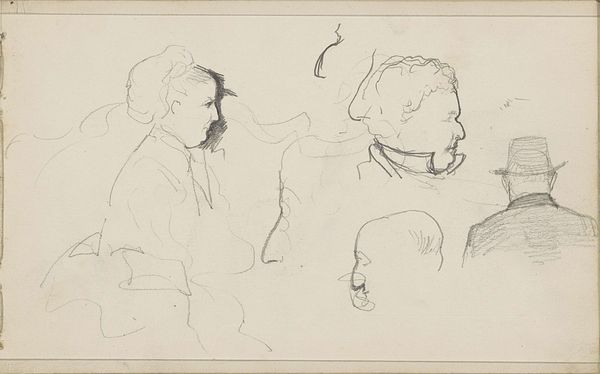

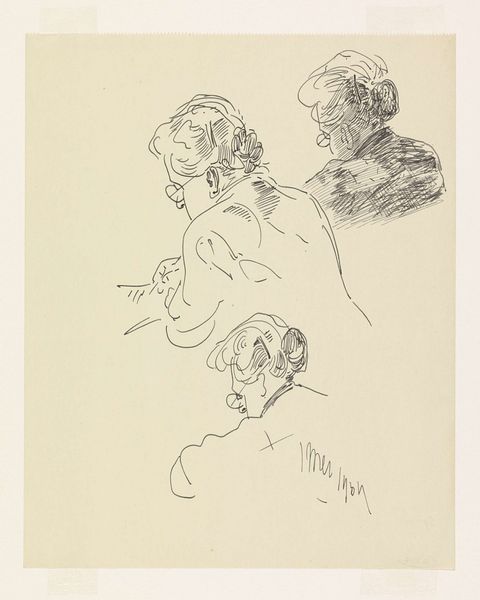

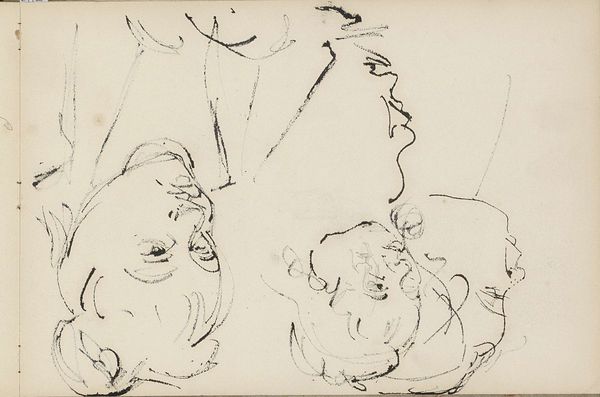

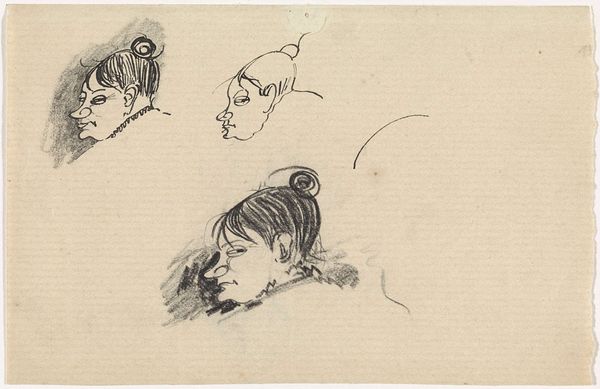

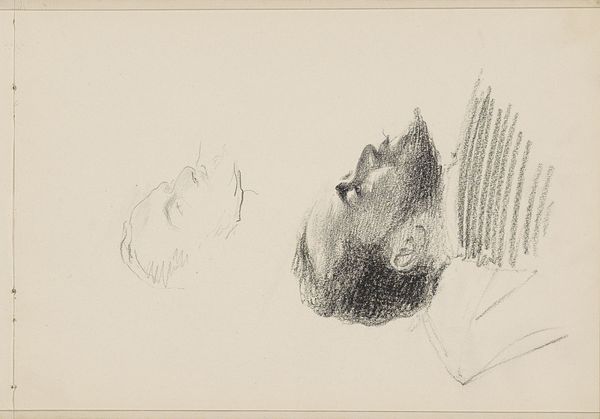

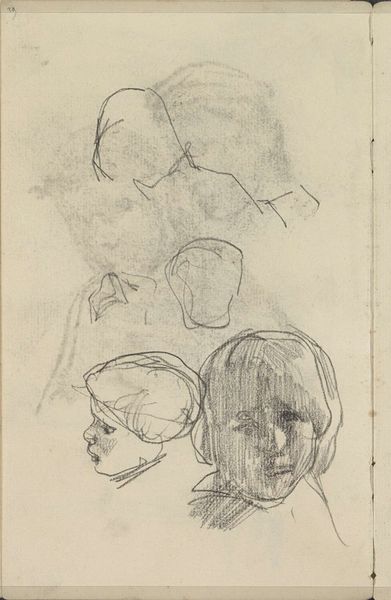

drawing, pencil

#

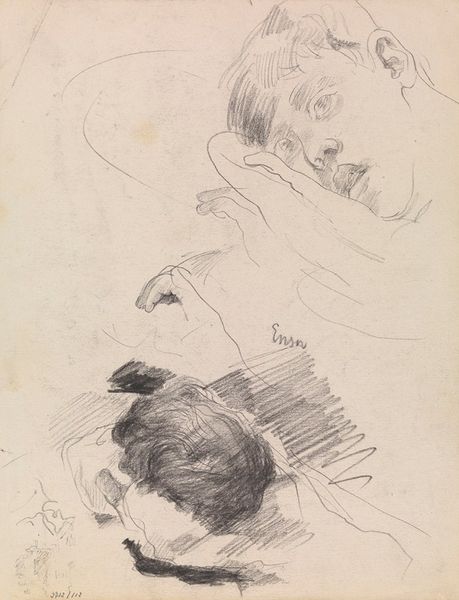

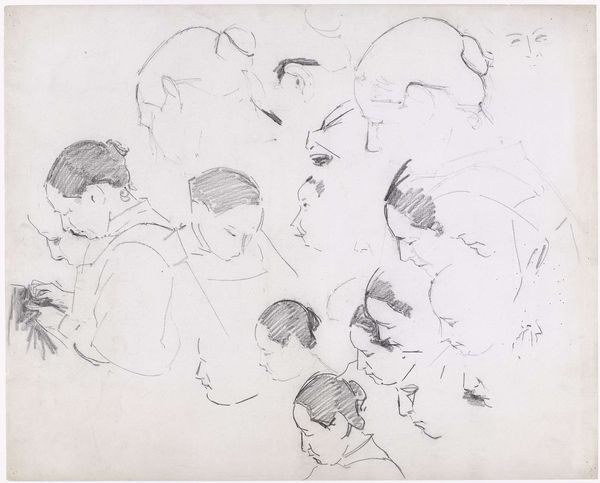

portrait

#

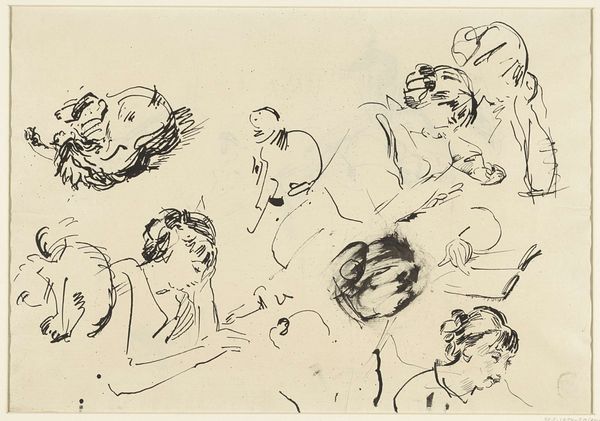

drawing

#

imaginative character sketch

#

art-nouveau

#

self-portrait

#

quirky sketch

#

impressionism

#

cartoon sketch

#

personal sketchbook

#

idea generation sketch

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 175 mm, width 275 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: There's a quiet intimacy about these sketches, isn't there? They almost feel like stolen moments. Editor: Indeed. What we’re observing is "Twee schetsen van het hoofd van een vrouw" by Gerrit Willem Dijsselhof, likely created between 1876 and 1901. It's a work currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. What strikes you formally? Curator: The economy of line, absolutely. Dijsselhof conveys so much with so little. Note the confident strokes defining the profiles, and how the shading creates volume. It's a study in contrasts, really, with those softer, smudged areas alongside crisp edges. Editor: Agreed. But thinking historically, portraiture often served specific social functions—status, commemoration. How do these seemingly informal sketches fit into that context? Were these commissioned? Curator: Unlikely. My impression is that they weren't intended for public display at all. They possess a casual nature; their charm is the artist's quick record of everyday existence, unburdened by social requirements. Editor: Perhaps it was a sketchbook exercise? Idea generation for the bigger commission that the artist took on after? Curator: Exactly. And it's precisely that rawness and authenticity that allow us, more than a century later, to glimpse not just a woman's likeness, but, maybe, her inner life and also a quick sketch of the artist's mindset. We also see how art-nouveau and impressionism influences are evident through the medium. The strokes of impressionism that were made to present realistic elements, yet it follows an abstract presentation that is very characteristic of art-nouveau. Editor: An intimate conversation between artist and subject, filtered through time. It’s intriguing to think how these sketches resonate within a larger art-historical narrative. It presents an evolution of thought that art is always trying to pursue in an honest manner. Curator: Yes, in some ways, by capturing her silent gaze, Dijsselhof unintentionally made the subject complicit with history as well.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.