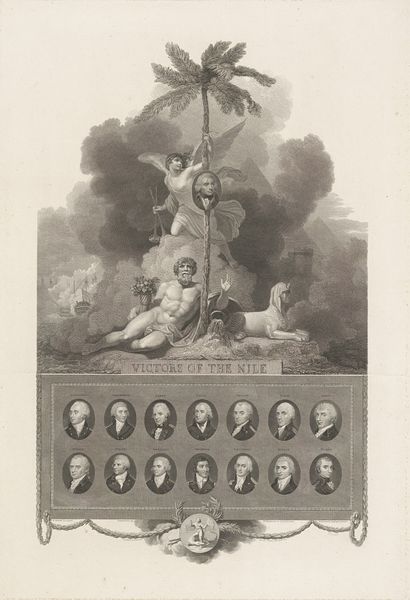

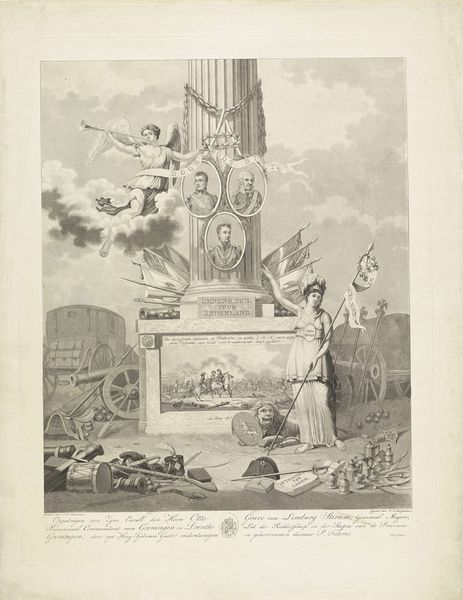

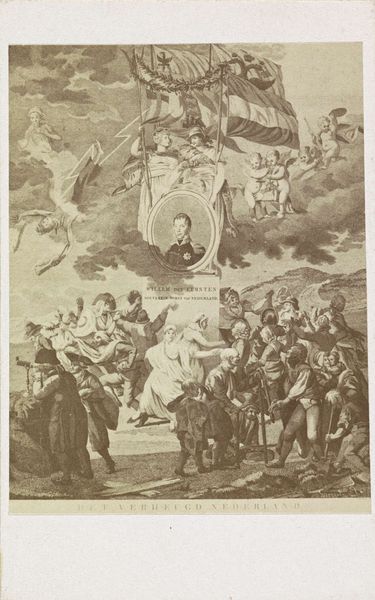

Gedenkplaat bij 300 jaar slag van Heiligerlee, 1568-1868 1868

0:00

0:00

rombertusjulianusvanarum

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 478 mm, width 400 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Well, that's busy! A real flurry of lines and historical portent. Editor: Indeed. We are looking at an engraving created in 1868 to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the Battle of Heiligerlee. The piece, titled "Gedenkplaat bij 300 jaar slag van Heiligerlee, 1568-1868," is currently held in the Rijksmuseum. Its creator, Rombertus Julianus van Arum, really packed in the symbolism. Curator: You're right. It's positively teeming! But I like how theatrical it feels, almost like a stage set for a historical drama. Those figures looming on either side, like statues come to life. Are those meant to be leaders of the conflict, perhaps? Editor: Precisely. They flank a central scene that appears to depict the battle itself. What strikes me is how the romanticized imagery serves to construct a very specific narrative around Dutch identity and nationhood. The woman seated on top with the lion evokes ideals of strength and liberty, yet what perspectives are notably missing in this celebratory tableau? Curator: Hmm, it's very Eurocentric, isn’t it? This idealized Dutch lion seems oblivious to the wider colonial context of that era. I suppose that rosy glow of 1868 celebrates one thing, while obscuring a great deal more. What did the artist intend by including those smaller portraits in the lower register? Are those more participants or heroes, maybe? Editor: The portraits below likely serve to further cement a particular version of history— emphasizing individual actors within the grand sweep of events. It also follows conventions in history painting and romanticism. We are asked to understand that events and collective identities are formed by individual (and of course masculine) actors. This reinforces power structures and privileges certain stories above others. Curator: It's an intriguing object, no doubt, though perhaps too convinced of its own virtue. There's little space for nuance in this celebratory style. Do you feel such historical commemoration still holds value in a contemporary context? Or is it inevitably tainted by a kind of blind patriotism? Editor: These objects are incredibly useful for thinking through the narratives we construct and then pass on through generations. Monuments and prints alike reveal just as much by what they exclude. Reflecting critically about why and how these symbols emerge and become popularized is how we equip ourselves for the task of building a future for collective liberation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.