photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

landscape

#

photography

#

romanticism

#

gelatin-silver-print

Copyright: Public Domain

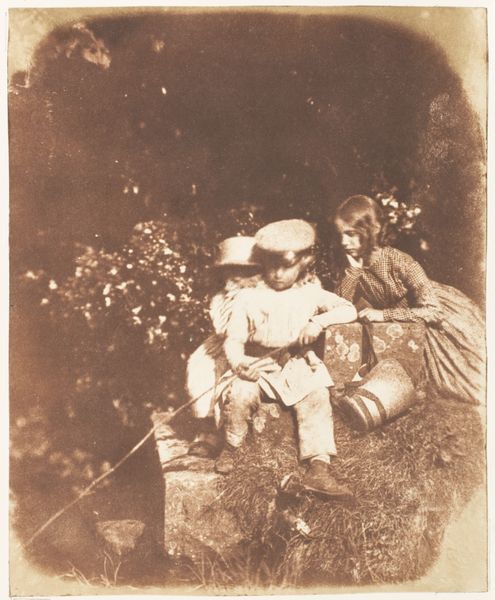

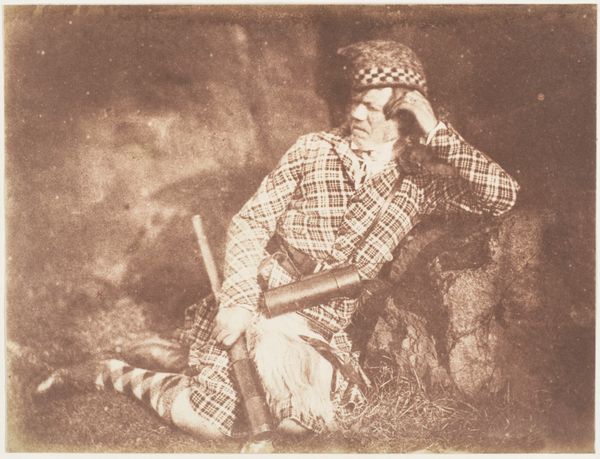

Curator: This is "Master Finlay," a gelatin-silver print, by Hill and Adamson, dating from around 1843 to 1847. Editor: It’s strikingly peaceful. The boy asleep in the grass; a worn hat nearby. There's a tangible stillness to the composition. Curator: Absolutely. This image embodies elements of Romanticism, seen through the lens – quite literally – of early photography. We might read Finlay's repose as an expression of freedom from social constraints, typical for the period's idealized vision of childhood. Consider also the emergent tensions surrounding class and labor in Scotland at this time. Editor: That relationship with the land seems significant. Given the work involved in producing a gelatin-silver print, the very materiality contrasts starkly with Finlay’s seemingly carefree slumber. The process itself was labor-intensive; chemicals had to be mixed and plates carefully coated. It represents quite a dedication to capturing this fleeting moment. Curator: And there's a deliberate construction at play here. Though seemingly spontaneous, "Master Finlay" likely was staged. Think about how deeply gender and class informed these carefully-crafted portraits in the 19th century. What did it mean to portray a young boy in this manner, seemingly connected so profoundly to the land? Editor: It's fascinating to consider how this image circulated then, and what value it held to the various viewers and owners over the decades. I keep thinking of the actual grass itself; each strand captured as evidence, or even a memento of lived life. Curator: This piece invites us to reflect on what constitutes ‘labor’ in art – not only Finlay's unseen labor as a child, but also the complex socio-economic relationships woven into the photographic process itself. And more broadly, the political meaning of leisure itself. Editor: For me, this brings forward a compelling look at the means of representation – how a moment is painstakingly recorded, almost preserved – through careful construction. Curator: Considering this photograph reminds us to look deeper. Early photography was not a neutral act but was shaped by culture, class, and rapidly changing technology. Editor: Yes, exactly, and that even a "simple" portrait has its origins in a convergence of social forces, materiality, and craft.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.