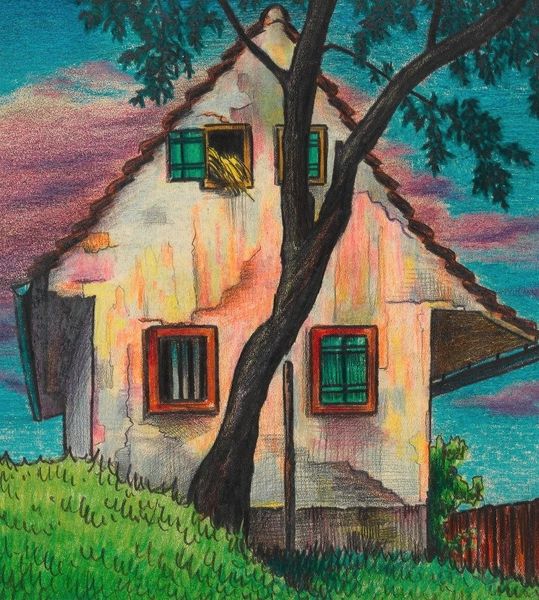

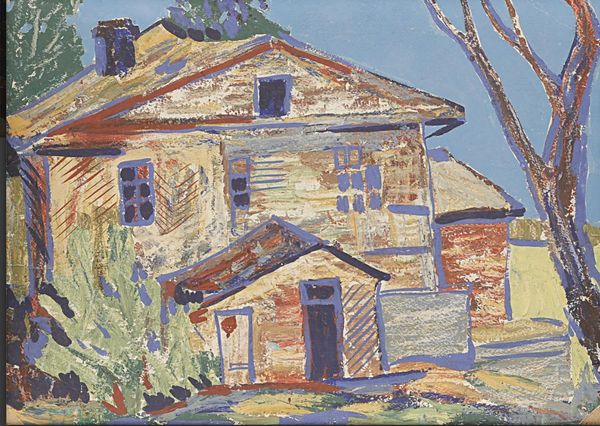

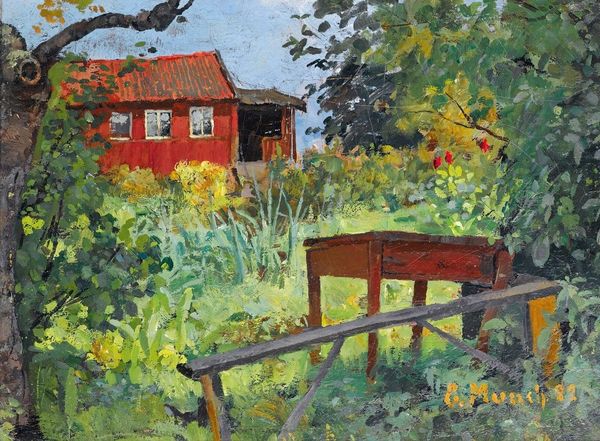

drawing, coloured-pencil

#

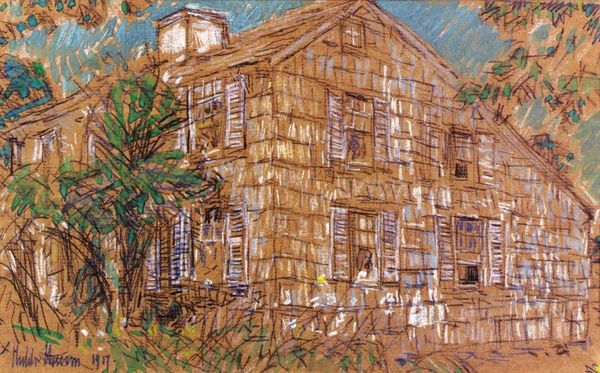

drawing

#

coloured-pencil

#

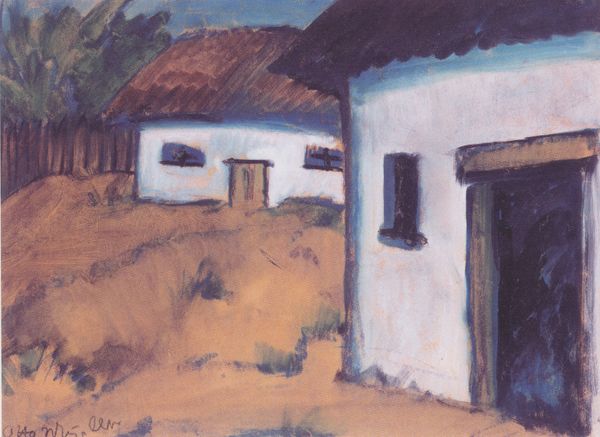

abstract painting

#

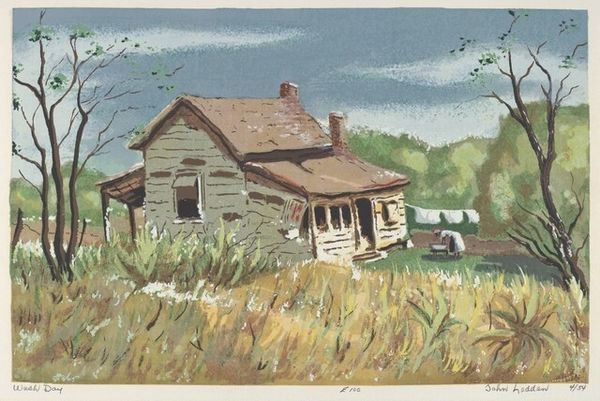

landscape

#

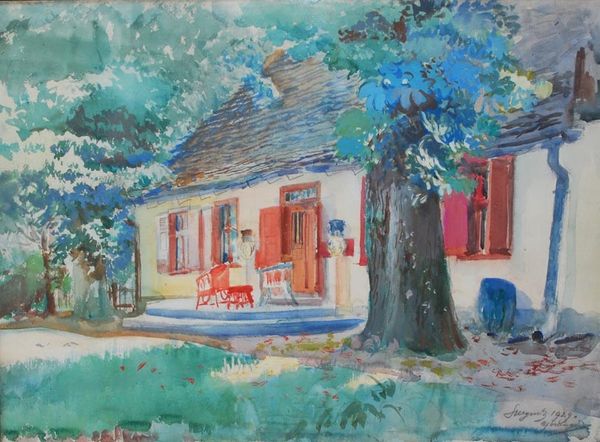

impressionist landscape

#

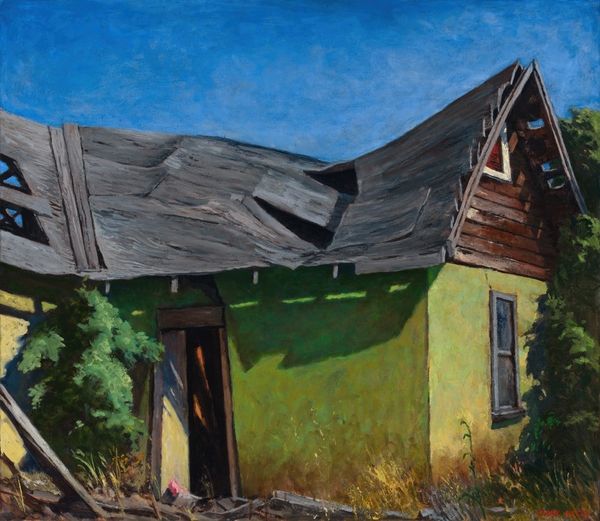

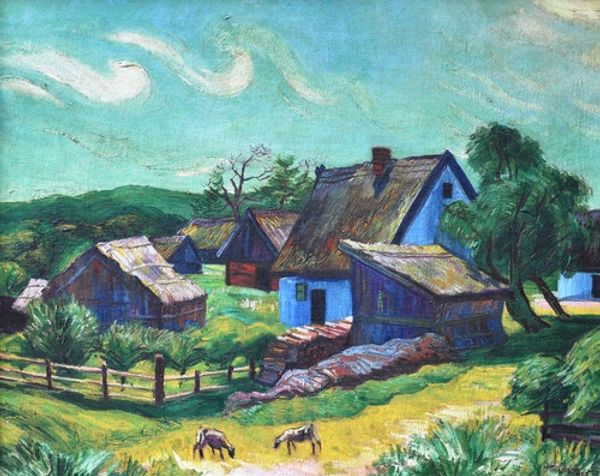

oil painting

#

expressionism

#

expressionist

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

Curator: Here we have Karl Wiener’s “Küchenhaus Hundsdorf,” dating to around 1925, rendered in colored pencil. What's your first take on it? Editor: The sun-drenched hues create an immediate impression of rustic tranquility. There's an intimacy to the scene—it feels like a personal refuge rendered in warm tones, yet tinged with an awareness of isolation. Curator: The choice of colored pencil, rather than paint, speaks volumes. There’s a tactile immediacy. I'm interested in how Wiener depicts everyday architecture—a vernacular structure rendered with such deliberate artistic choices. How does this subject position itself within the historical context? Editor: Considering Wiener's Jewish heritage and the rise of exclusionary politics in the interwar period, such idyllic imagery offers a lens to interpret this artwork as a potential form of resistance or escapism. It perhaps served as an act of claiming space, tradition, and beauty against an encroaching environment of persecution. What materials draw your attention? Curator: Absolutely the layers of colored pencil. Notice the roughness of the paper texture coming through, juxtaposed against the smooth gradations of light and shadow on the building's facade. There's a visible trace of the artist’s hand in the act of creation. The medium serves the dual role of both portraying and critiquing idealized rustic life as material and visual experience. Editor: I see it resonating with early twentieth-century anxieties. While seemingly idyllic on the surface, consider the implications of longing for an uncomplicated existence. How might that interact with, or react against, the sweeping political changes happening at the time? Are we invited to escape into nostalgia, or contemplate our role within rapidly shifting societal landscapes? Curator: It invites an awareness of artistic processes as a vehicle for experiencing cultural conditions. By foregrounding the deliberate construction of the image through layered pencils, Wiener lays bare a consciousness of place, belonging, and memory itself as a constructed commodity. Editor: Perhaps such detailed rendering allowed for maintaining the artist's identity during times of conflict. Curator: Exactly. Through his medium and attention to production and construction, Wiener made the invisible visible. Editor: In viewing "Küchenhaus Hundsdorf", we aren't just observing an image; we are engaging with a dialogue between the artist, his time, and our own interpretation. Curator: I agree; thinking about the artist's labor really changes how we interpret his emotional investment.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.