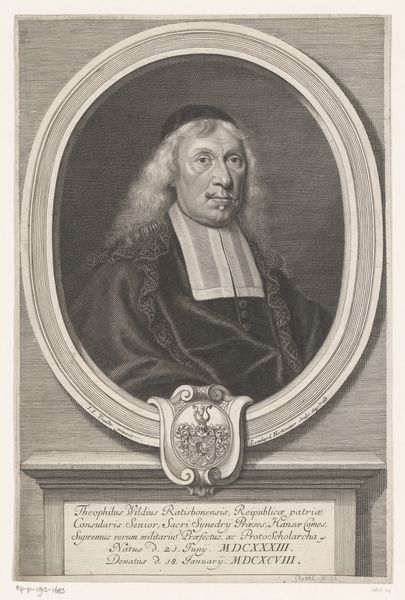

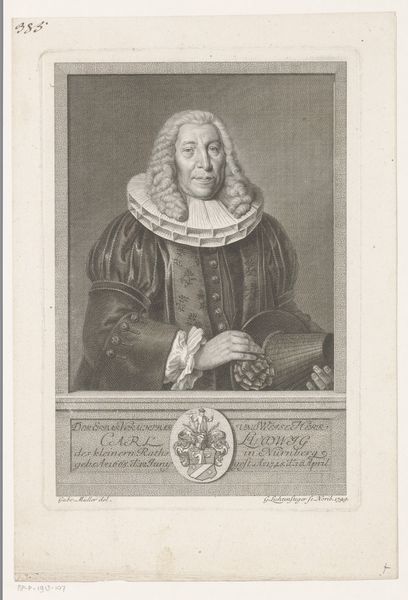

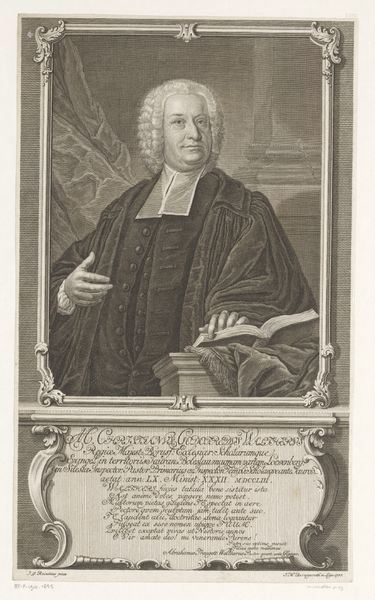

Portret van Georg Christian Woytt op 44-jarige leeftijd 1727 - 1783

0:00

0:00

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

old engraving style

#

charcoal drawing

#

portrait reference

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 360 mm, width 252 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We’re looking at a compelling engraving from sometime between 1727 and 1783. It's a portrait of Georg Christian Woytt at 44 years old. Editor: It’s immediately striking – the careful rendering gives it a sense of solemnity, even…gravity. The subject’s gaze, coupled with the formality of the attire, projects an aura of authority, I would say. Curator: Indeed. The artist, August Hermann Jakob Degmair, clearly prioritized detail. Look at the elaborate swirls of Woytt’s wig, how each curl is meticulously etched. Then see how that intricacy is mirrored in the ornate frame itself, and the detailed coat of arms displayed below. Editor: The use of engraving allows for very high contrast, further emphasizing this. I find myself wondering about Woytt’s place within the societal structure of his time. The inscription describes him as Court Preacher and City Pastor - these would have been significant roles that gave Woytt a powerful public voice, a social influencer, if you will, whose religious pronouncements no doubt affected his congregants daily lives. Curator: Precisely. And you see how Degmair captures the textures of his garments? There’s a tactile quality evoked through the precise linework, suggesting silk or fine wool. These details speak volumes about Woytt’s status. There is an element of refinement to this portrait. Editor: And that hand placement? Held formally to his chest, it signals piety and a sort of stoic determination. We can read the gaze, the clothing and the text on the print to reconstruct his life and social standing in the German town of Ottweiler, back in the 18th century. It also makes me consider how the development and proliferation of early print-making techniques like engraving facilitated these types of social role definers and promoters. Curator: A superb point! The formal composition creates a self-contained world, reinforcing the subject’s importance and separation from the viewer’s everyday life. Notice the visual weight that Degmair gives Woytt's right hand that's prominently placed and subtly lit. Editor: Seeing this through an intersectional lens reveals how power was visualized, reinforced, and disseminated in the 18th century. The engraving is not merely a picture; it’s an assertion. Curator: I'm struck by how the structural elements create a clear statement on the man. It allows for multiple ways to understand Woytt’s world. Editor: Agreed. Reflecting on it, it makes you wonder about the countless other stories silently embedded within portraits, quietly waiting to be reactivated by our present-day gaze.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.