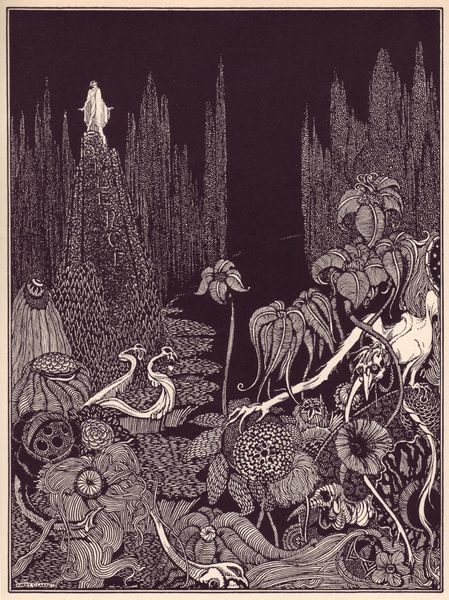

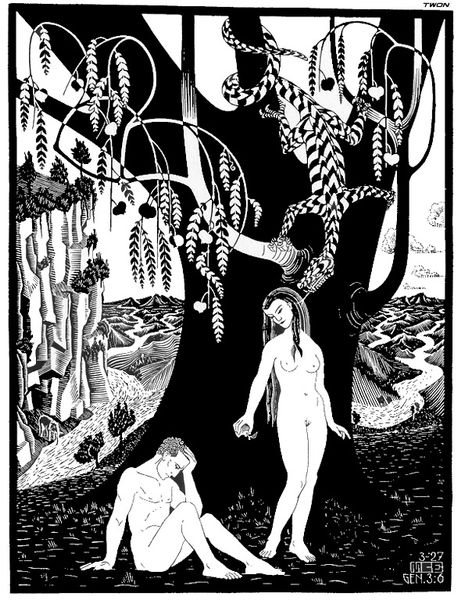

drawing, print, woodcut

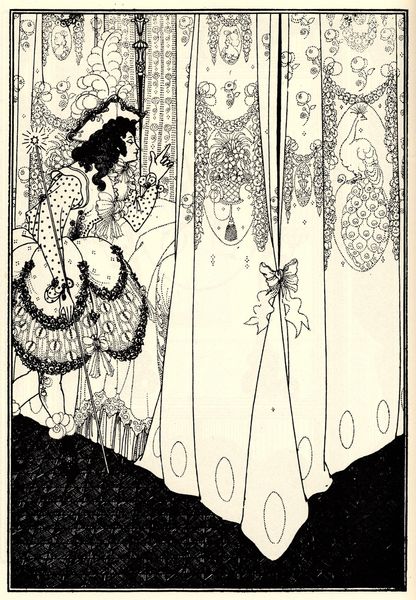

#

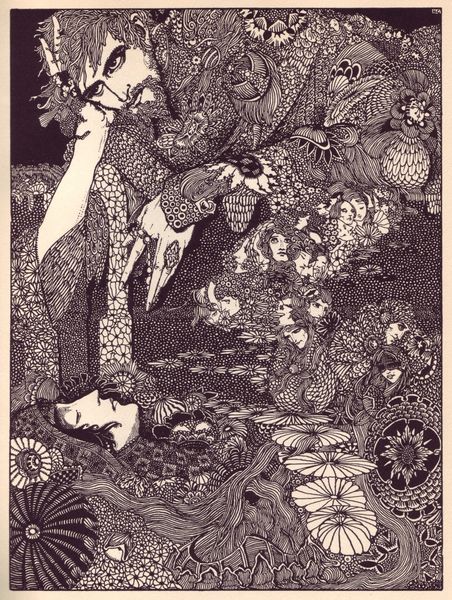

drawing

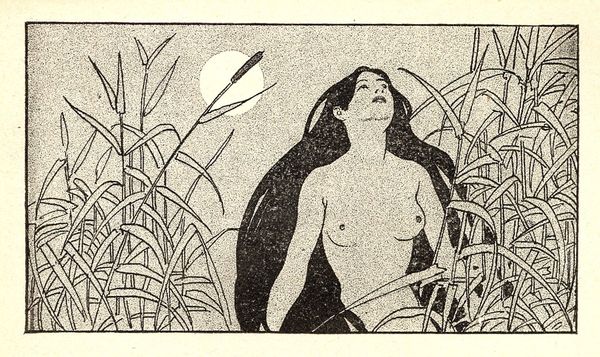

#

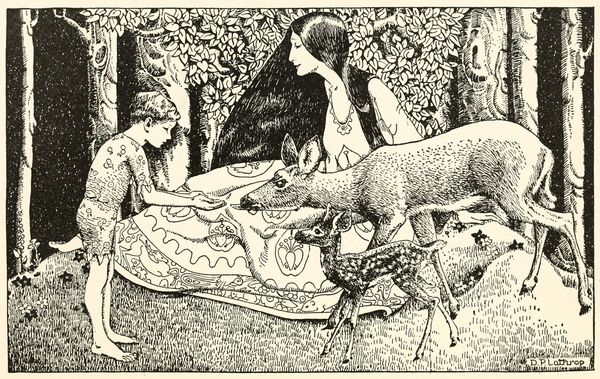

line-art

#

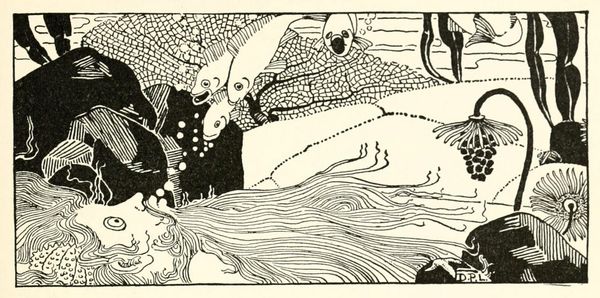

allegories

#

allegory

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

line art

#

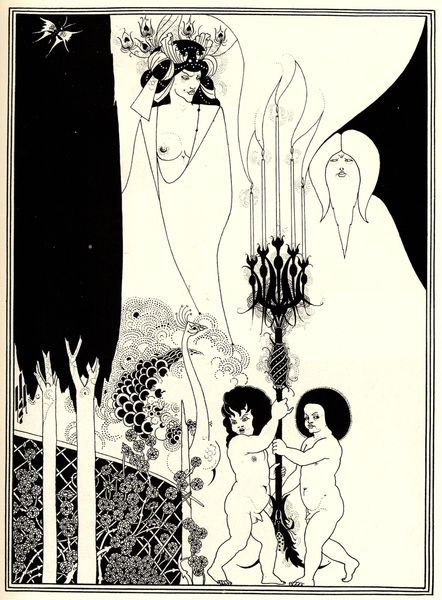

female-nude

#

woodcut

#

history-painting

#

nude

#

male-nude

Copyright: Public domain US

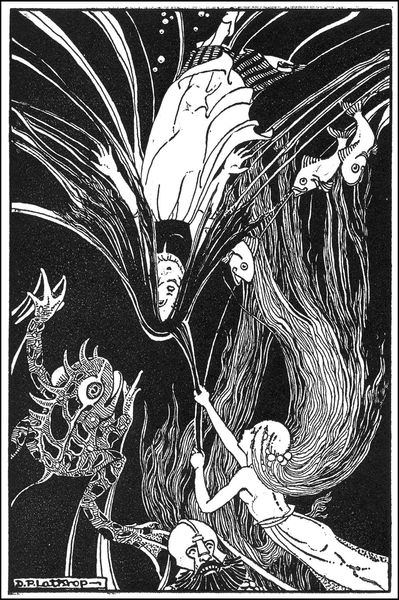

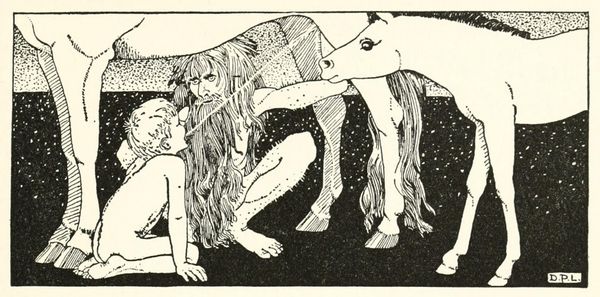

Curator: At first glance, M.C. Escher’s 1921 woodcut, "Paradise," has an unsettling, almost austere quality, despite its subject matter. It reminds me of a medieval tapestry somehow, even though Escher's style is distinctly his own. Editor: Unsettling is a good word. I get this sense of… theatrical staging? All the animals arrayed just so, like characters in a play, almost posed. It’s definitely not the riotous abundance I’d expect from paradise. Curator: The stark black and white contributes to that feeling, doesn’t it? Escher primarily used woodcut here, a medium demanding strong contrasts. I see so many symbols woven together in this very organized image—Eden’s key inhabitants presented, but void of that inherent innocence. It's as if this paradise is presented already fallen, not exactly teeming with life. Editor: You’re right about the lack of innocence. Adam and Eve, rather stiff and elongated, feel more like marble statues than flesh and blood. The symmetry is…clinical, bordering on chilling. What is it that the presence of an owl normally signifies here? Curator: The owl, often associated with wisdom but also with darkness and death, becomes particularly charged in this setting. Its positioning directly above the tree separating Adam and Eve hints at knowledge gained and innocence lost. Note also how the animals themselves, traditionally symbols of harmony within paradise, feel somehow…contained. Even the light seems structured. Escher challenges traditional views by suggesting the shadow that exists even in perfect light, doesn't he? Editor: Absolutely. I suppose it also taps into that very human habit of wanting to impose order, even onto something as inherently chaotic as ‘paradise.’ Is it just me, or does that ape in the center look like it's smirking? Curator: The ape is an unexpected touch, isn't it? Perhaps a commentary on our own primal nature lurking beneath the surface of civilization, even in the garden of Eden. The work speaks of humanity’s dual potential: sublime creativity but also the inclination to dominate the very essence of our origins. Editor: It’s a far cry from a joyful Eden, more a tightly controlled diorama reflecting perhaps more the limits of human vision than any divine truth. I feel Escher did well here; to challenge the archetype rather than present a direct derivative of what came before him. Curator: Indeed. Escher presents not just a scene, but a statement. A visually arresting prompt inviting us to reflect on the nature of perfection and its potential constraints.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.