painting, oil-paint

#

neoclacissism

#

sky

#

abandoned

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

landscape

#

oil painting

#

romanticism

#

water

Copyright: Public domain

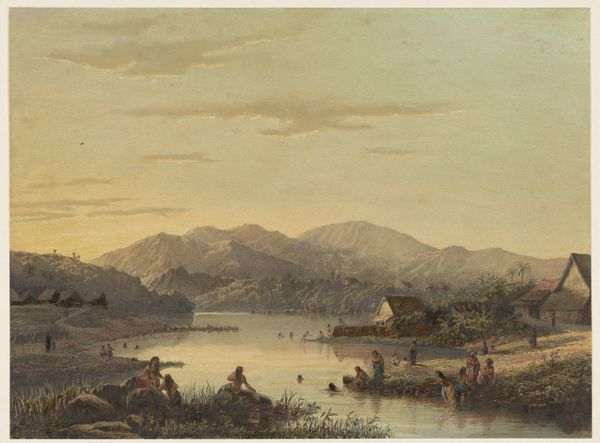

Editor: So this is Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld’s "Villa Carlotta À Tremezzo, Sur Le Lac De Côme", an oil painting showing a grand villa on the shores of Lake Como. There's a sense of serene privilege here, but almost to an unsettling degree. How do you read this image? Curator: The placid surface reflects more than just the architecture; it mirrors the socio-political undercurrents of the time. Doesn’t the imposing villa, with its seemingly endless terraces and meticulously ordered gardens, speak to the consolidation of power and the aestheticization of wealth? Editor: Absolutely, it's hard to ignore. The architecture really dominates. But isn't this a fairly common theme in landscape painting? What specifically makes you connect it to power? Curator: Because Bidauld wasn't simply painting a beautiful view. Consider the French Revolution's echoes during this period. Landscape painting, often commissioned by the elite, inadvertently became a stage for projecting dominance and claiming space amidst societal upheaval. Notice how the human figures are diminutive, almost incidental. Who exactly benefits from the abundance of this estate, and who is excluded? Editor: I see what you mean. The landscape itself becomes a symbol of control, with those tiny figures reinforcing the power dynamic. Curator: Precisely. This image isn't merely picturesque; it's a visual articulation of social stratification. Reflect on what it means to curate an ideal view. What's included? What's omitted? Who gets to decide? Editor: This has totally shifted my perspective! I came in thinking about picturesque beauty, and now I am leaving with the image as a visual power statement. Curator: Good, and consider further that the aesthetic pleasures we derive from art can often be intertwined with complex issues of access, representation, and ultimately, justice.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.