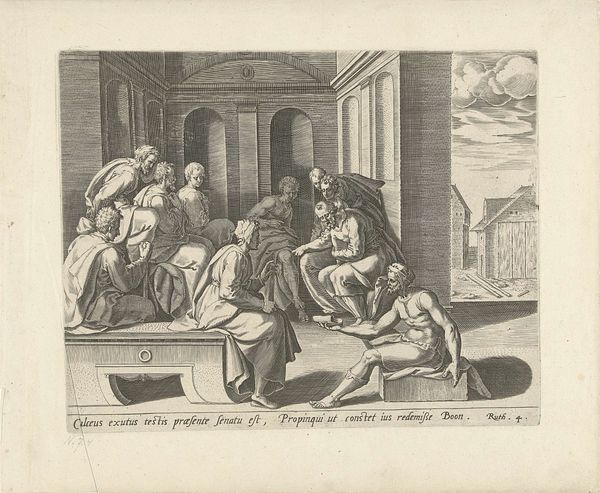

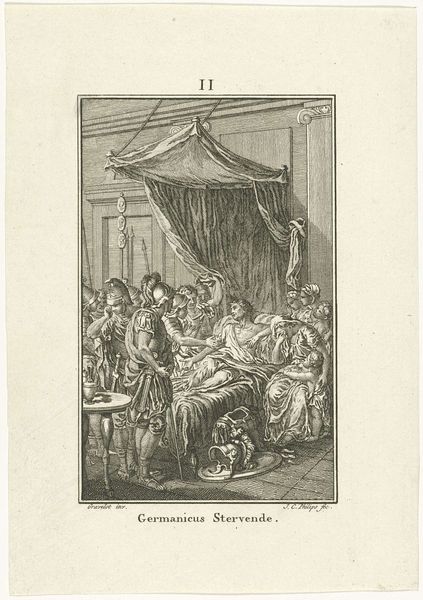

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 308 mm, width 203 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving, "De hongerigen spijzigen" – "Feeding the Hungry" – was created by Gerrit de Broen after 1695, placing it firmly in the Dutch Golden Age. It is part of a series illustrating the Works of Mercy. Editor: It's so evocative, even in this monochrome. The way the light falls across the scene gives it an almost theatrical quality. The figures are positioned beautifully, but there is a definite social dynamic in their staging that is visible, it almost gives you pause to inspect its meaning and how you interact with the work. Curator: Absolutely. De Broen was working within a society wrestling with ideas of poverty, charity, and the individual’s role within the community. It's fascinating to see how artists visually translated those social anxieties and emerging ethics, given how strongly they impact current views and society. Editor: I am reminded of many other visual art renderings, the act of giving – providing basic needs like food – carries enormous weight within religious narratives as it does in culture. But there's also a sense of precariousness here; is it performative charity, or does it indicate the values held within? Is this the norm of generosity and selflessness we could see in the common areas for others? Curator: That tension is very much present in 17th-century Dutch society. On the one hand, burgeoning wealth allowed for grand gestures of philanthropy. On the other hand, rigid social hierarchies were constantly being reinforced. An artistic lens examining this point, questions the act and the implications behind it. Editor: The very act of visually representing charity then becomes a complicated maneuver. The choice to portray it for viewing raises several ideas about performative acts. The engraving serves both as documentation but perhaps subtly reinforces prevailing societal attitudes about wealth and inequality. It’s interesting to see how the placement of this work affects us today. Curator: Indeed. By looking at these older prints through the prism of current socioeconomic debates and our society, we gain a clearer understanding of not only Dutch Golden Age aesthetics and the artistic landscape but how values are being built around social standing. Editor: I completely agree; it challenges us to unpack both historical contexts and to examine our own biases about issues of social inequity. These social acts we have a strong inclination to feel we understand, but as these images show us, a more robust lens that takes the values of the act into consideration is more in line with ethical understanding.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.