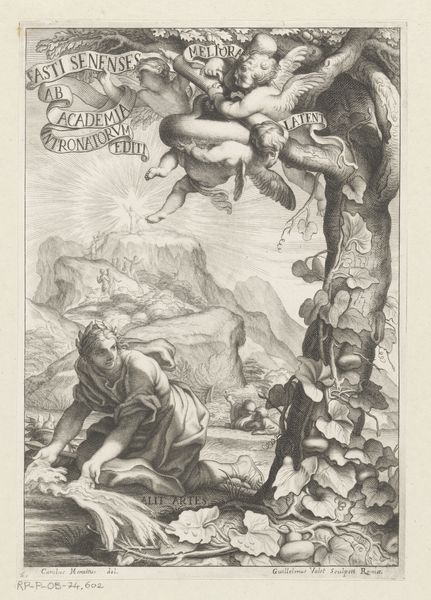

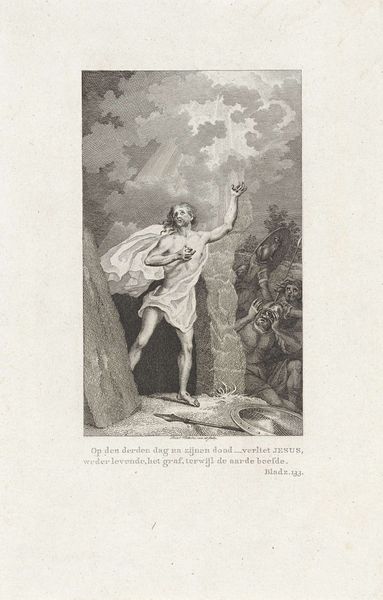

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

pen-ink sketch

#

line

#

pen work

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 154 mm, width 100 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let’s talk about Jan Gerritsz van Bronckhorst's 1637 engraving, "Jongen met stok bij grot," or "Boy with Stick by Cave," housed here at the Rijksmuseum. The work immediately strikes you, doesn’t it, with its precise lines? Editor: It does. Stark. The boy looks rather theatrical; his pose is... intense, as if trying to decipher secrets from the very rock itself. Very melodramatic! I find myself focusing more on the materiality. It's interesting to consider the process of engraving back then, each line etched laboriously into the copperplate, the print itself a kind of multiple original. Who was consuming these images, and why? Were they pedagogical? Decorative? Curator: Perhaps both? Bronckhorst, as I understand him, saw printmaking as a conduit for both accessible art and as a showcase of skill. He would often reproduce the paintings of others to allow more people access, or engravings of his own works as autonomous drawings of mythological narratives and landscapes. In the case of this print, he used the pen work in a similar style to create this pen-ink sketch that gives it a baroque line feeling, as the main character takes part in what can be understood as historical paintings. He may have drawn inspiration from artists like Cornelis van Poelenburgh or Abraham Bloemaert who painted Italianizing landscapes in and around Utrecht during this time, and with whom it seems Bronckhorst maintained close relations. But this almost performative air is what grips me here! Is the boy an oracle? A prophet? Why a cave? Why that specific staff? I can’t help but imagine what stories he carries—is he acting it out in front of the mouth of the cavern? Editor: Well, the cave as symbol has resonated for millennia - the cavern of the unknown, the maternal darkness. The staff would likely be an indication of guidance, the rocky exterior of the mouth seems to imply a perilous entry and what, precisely, awaits inside. What did this accessibility mean? Who had the time and the means to collect prints? Considering the material conditions under which it was made, can we truly call it “accessible?" These aren’t mass-produced posters. Curator: Touché. We’re dancing around a fascinating paradox, I suppose. Yet, when gazing at it now, centuries removed, it makes you appreciate the craft, every cut, every stroke considered and calculated to give this feeling of a boy uncovering history or even inventing a new history to become. Editor: Absolutely. By foregrounding the material processes and reception context, we gain a deeper understanding of not just what the image represents, but what it meant, and how it functioned within its own time. And it helps remind us of our responsibility in engaging in images such as these, since in our current context they represent even more than the sum of its physical making. Curator: Agreed. Every view is another entry point, I guess, not unlike stepping into that very cave!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.