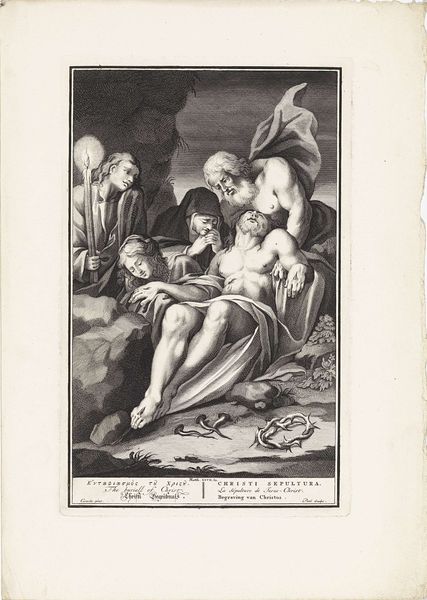

Dimensions: 237 × 175 mm (image); 271 × 194 mm (primary support); 432 × 297 mm (secondary support)

Copyright: Public Domain

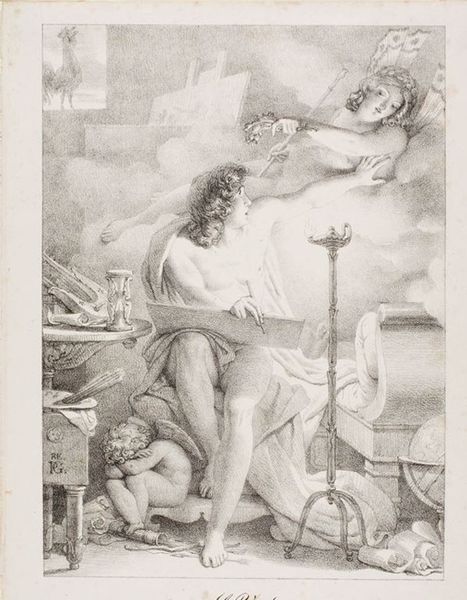

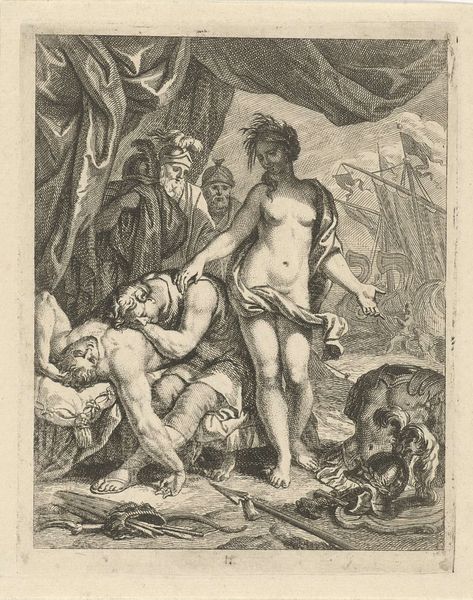

Editor: Here we have "Plate Four from Misery," a lithograph created by Charles Rambert in 1851. It's currently held at the Art Institute of Chicago. There’s a strong feeling of darkness and despair that emanates from the print… almost nightmarish. What do you see when you look at this work? Curator: Nightmarish is a wonderful descriptor, it reminds me of a fractured fairytale, perhaps something the Brothers Grimm left on the cutting room floor! I'm drawn to the contrast between the ethereal scene above and the earthly suffering below. Notice the gaunt figure whispering, perhaps planting seeds of envy. It’s as if Rambert is showing us a battle for the soul. What do you make of the sleeping family in the lower left corner? Editor: They look peaceful, oblivious almost, to the drama unfolding above. They're wrapped in this soft, dreamlike state, contrasting sharply with the tense figure being tempted. Curator: Precisely! The sleeping family embodies innocence, while the standing man embodies a crossroads, a moral dilemma if you will. Consider the historical context. 1851 France, a time of immense social upheaval. Rambert, through Romanticism, offers a raw commentary on poverty and its corrosive effects, where envy and desperation gnaw away at the soul. Editor: So it's like, misery preys on those who already have nothing to lose? Curator: Exactly! Misery, personified, whispers the promise of escape through questionable means. But is it truly escape, or just a deeper circle of hell? I love how the bright, almost heavenly scene with figures who 'arusent de tout' seems like a cruel taunt. The inscription states how “misery shows man, who has hunger, those who profit from everything”. This highlights the dark irony that the promise of such gain creates hatred and envy. The composition, too, pushes the viewers gaze, it urges one to delve into it, feel it… which, admittedly, is profoundly unsettling. Editor: That’s powerful, I see it now! It’s more than just a depiction of poverty; it's an exploration of its psychological toll. Curator: And isn't it fascinating how a print from almost two centuries ago can still resonate with us today, provoking thoughts about social justice, inequality, and the human condition? A successful piece does just that!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.