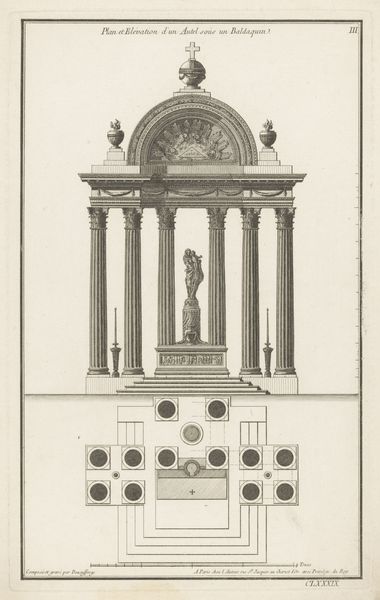

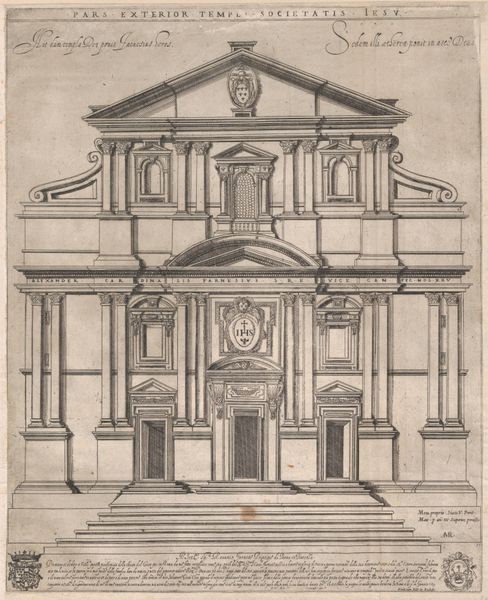

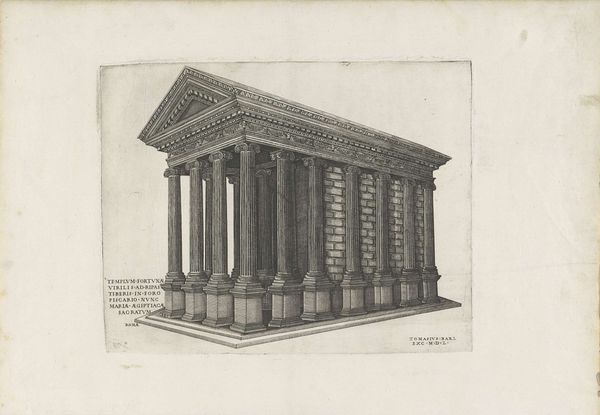

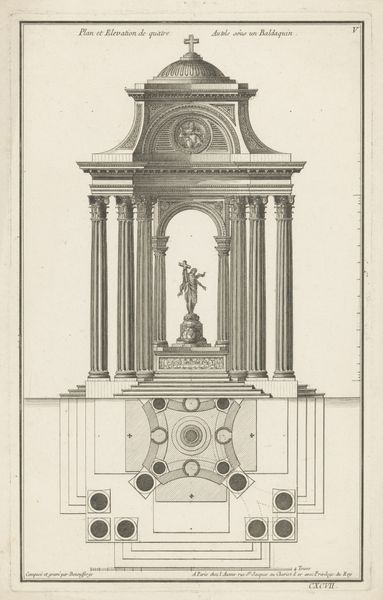

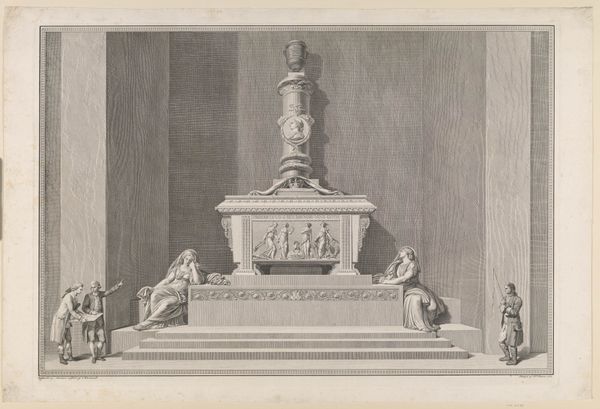

drawing, pencil, engraving, architecture

#

drawing

#

neoclassicism

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

geometric

#

pencil

#

line

#

cityscape

#

pencil work

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 195 mm, width 200 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This drawing by Antoni Zürcher, dating from 1816-1817, depicts an "Ereboog voor het stadhuis," or Triumphal Arch for the Town Hall. It's currently held in the Rijksmuseum's collection. Editor: My first impression is of stark monumentality, almost oppressively so. The repetitive columns and that heavy dome—it feels very much about power, but coldly so. And look at how precisely rendered, like an architect’s blueprint rather than a celebratory image. Curator: That’s a perceptive reading. This wasn't meant as mere decoration; triumphal arches served as powerful tools of statecraft. Erected for royal entries or significant national events, they communicated legitimacy and reinforced social order, and in this particular case, most likely it was commissioned to mark the return of William I to the Netherlands as sovereign after the Napoleonic Era. The placement in front of the town hall specifically links royal authority to civic governance. Editor: And what about the materiality here? This meticulously crafted drawing mimics the look of an engraving; so, the materials of a disposable and relatively cheap media simulate high-art traditions. Also, all those engraved details suggest mass production. Was this design meant to be disseminated widely? What does that suggest about the purpose of the actual, physical arch that never materialized? Curator: Exactly. The choice of inexpensive materials points to wider dissemination, possibly through prints, aimed at solidifying public support. By controlling the narrative through reproducible imagery, authorities sought to influence popular opinion, associating William I with a return to order and prosperity after years of upheaval. Editor: The neoclassical style is itself significant here. The column motif suggests a revival of the architectural tradition that originated in ancient Greece and Rome to reflect the grandeur of those empires, so associating it with William and Netherlands implies a sense of imperial stability for his monarchy at home and in its colonies. I would be curious to know the names of the artisans hired to build and later dismantle that construction after the parades celebrating the regime were over, the amount of wages paid, where did they came from. Curator: That's a great question about labour relations that art history has often overlooked. Zürcher’s "Ereboog" shows how art became intrinsically entwined with statecraft, using classical motifs and meticulous reproduction to build political consensus in a rapidly changing world. Editor: I am leaving with an appreciation for how an ephemeral and never realized artifact continues speaking volumes about power, the social fabric, and, fundamentally, what gets built, who builds it, and what remains behind.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.