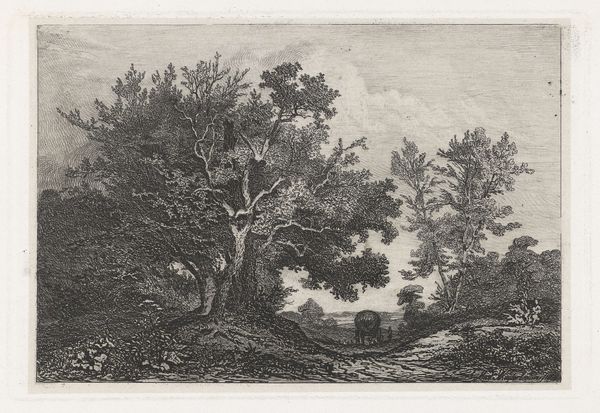

drawing, paper, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

river

#

paper

#

ink

#

romanticism

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 119 mm, width 178 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is "Riviergezicht bij Düsseldorf," a landscape drawing from 1848 by Jean Théodore Joseph Linnig, created with ink on paper, through an engraving technique. It strikes me as a very tranquil scene. How do you interpret this work, particularly considering the context of its creation? Curator: The tranquility you observe is characteristic of the Romanticism movement, yet, it also serves as a screen, masking the brewing social unrest across Europe in 1848, a year of revolutions. How might this idealized vision of nature function as a form of escapism or perhaps even a commentary on the socio-political landscape? Editor: So, instead of just being a pretty picture, it's interacting with the tense political climate? The focus on the "natural" might be a way of subtly critiquing or, as you said, escaping the issues of the time. Curator: Precisely. Consider the emerging industrial revolution and its impact on the environment and society. By glorifying untouched nature, Linnig may be subtly protesting against the encroachment of modernity and its consequences on class, gender, and identity. Notice also that the people on the river appear to be anonymous and ungendered. Why do you think this is? Editor: Maybe to highlight a sense of universal connection to nature, transcending societal roles, but maybe also a sort of erasure. The "common man", if you will, is at once centered, and invisible. What strikes me, then, is how the medium contrasts with its message. An engraving is so *constructed*, in comparison to the fluidity of the water. Curator: Exactly, that tension between the constructed image and the natural subject is crucial. The meticulous engraving reflects the desire for order and control, yet the subject matter, a flowing river within a landscape, hints at the untamable forces of nature and perhaps, by extension, the untamable desire for societal change. Editor: I see how situating the artwork within its historical and social context opens up so much meaning. I initially thought of it as just a landscape, but it's clearly engaged in a deeper dialogue. Curator: That’s the power of art history – to unveil these dialogues and connect the past with our present understandings of identity, power, and environment.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.