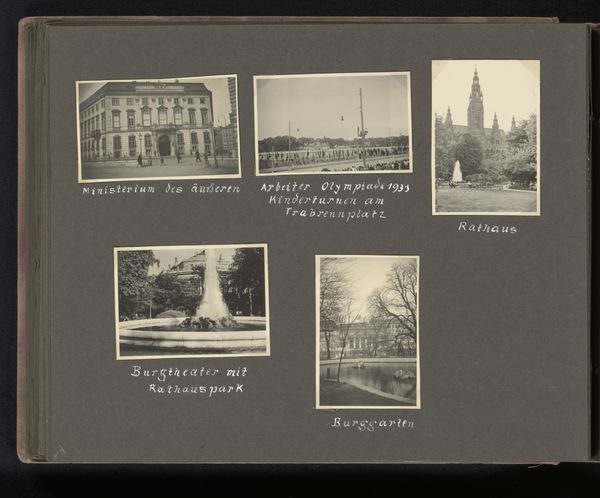

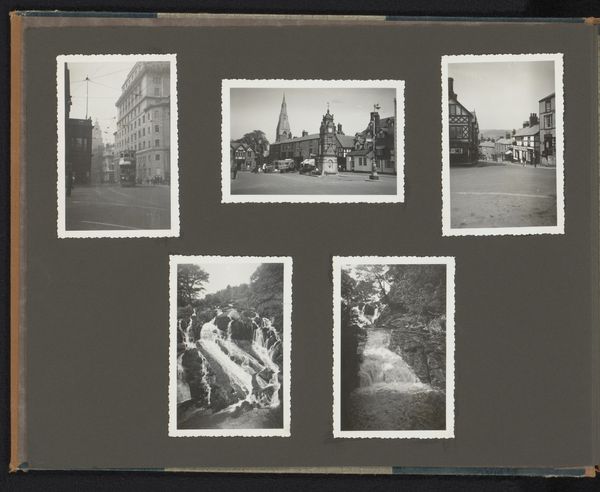

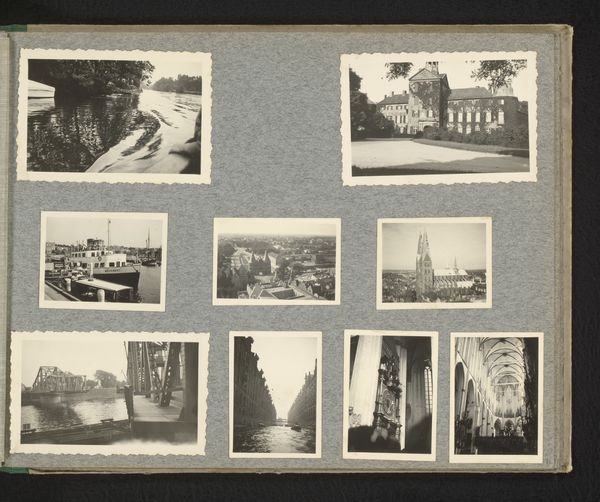

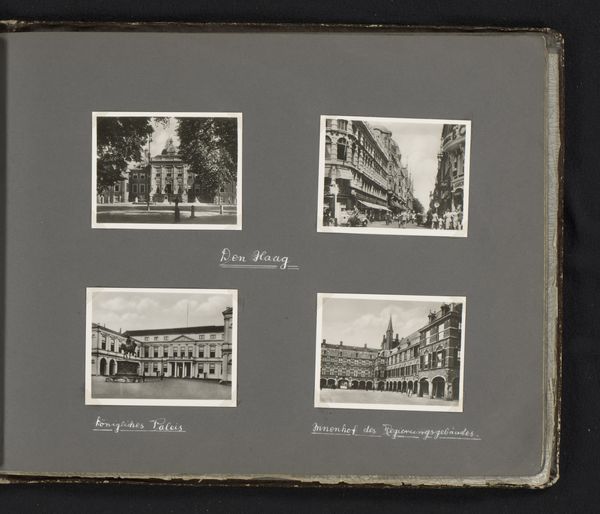

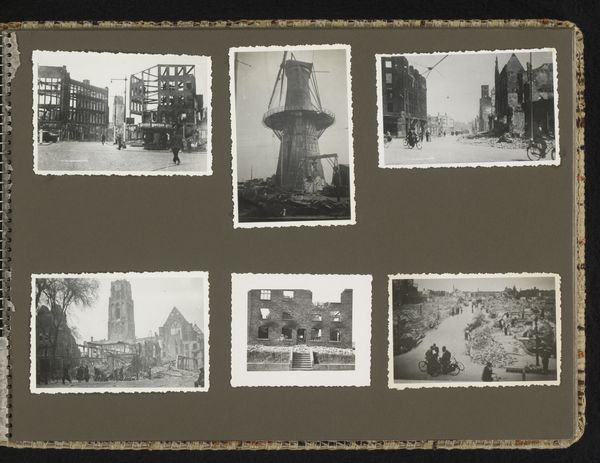

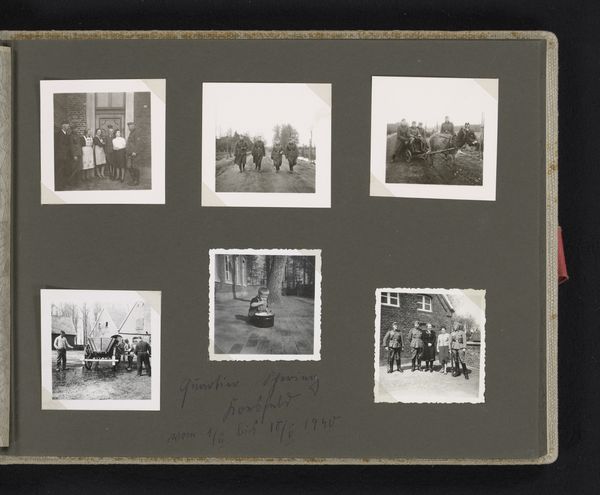

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

landscape

#

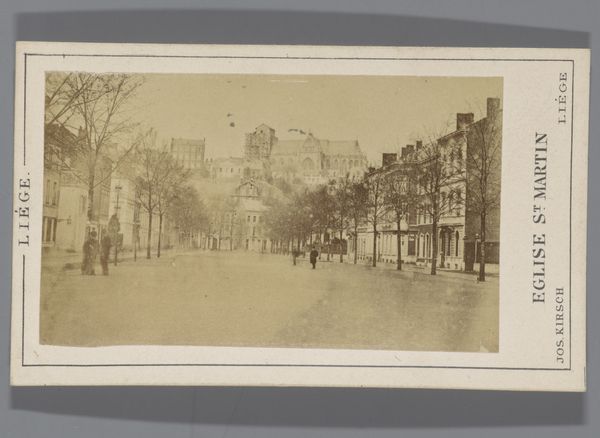

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

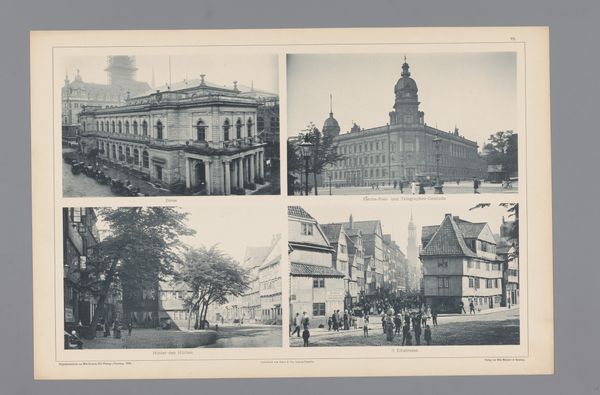

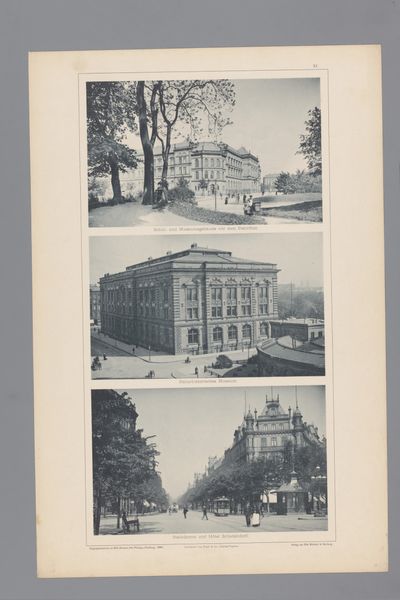

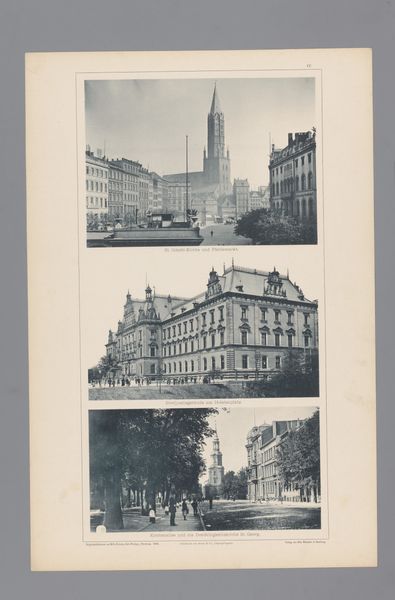

cityscape

Dimensions: height 60 mm, width 90 mm, height 210 mm, width 290 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is "Soldaten en Brussel," or "Soldiers in Brussels," a gelatin-silver print dating probably from 1940 to 1945, held at the Rijksmuseum. It’s a set of smaller photographs, almost like snapshots in a photo album, all showing architectural landmarks in Brussels with the unsettling presence of soldiers. What does this collection say to you? Curator: These aren’t just neutral depictions of Brussels; they're politically charged images created and circulated during a very specific moment in history. I notice the framing – placing the soldiers so prominently in the foreground, or alongside key national monuments, really emphasizes the occupation and the shift in power dynamics. What do you think was the intention behind such image making? Editor: Well, seeing soldiers positioned next to grand architecture definitely makes it seem like a claim of ownership, a visual statement of dominance. Maybe to project power back home or perhaps for propaganda? Curator: Exactly. Think about the role of photography during wartime. These images could be used to demonstrate control, to intimidate local populations, or as morale boosters back home. Consider how this album itself functions as a political artifact. Where was it meant to be seen? Who was the intended audience? These photographs, seemingly documenting a city, are truly documenting a conquest and the way power reshapes public space. Editor: So, looking beyond the surface aesthetics, these photos are a really potent commentary on how war and occupation alter not just physical space, but the social and political landscape too. I initially focused on the cityscapes, but the soldiers are impossible to ignore. Curator: Precisely. The contrast between the static grandeur of the buildings and the imposed presence of the soldiers reveals how the familiar can be manipulated to tell a very different story. A reminder of how easily imagery can become entangled with politics. Editor: I'll definitely think about the political subtext of photographs differently from now on. Thank you. Curator: And I am reminded how images meant to display power can now serve to document moments of historic subjugation, ripe for later deconstruction.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.