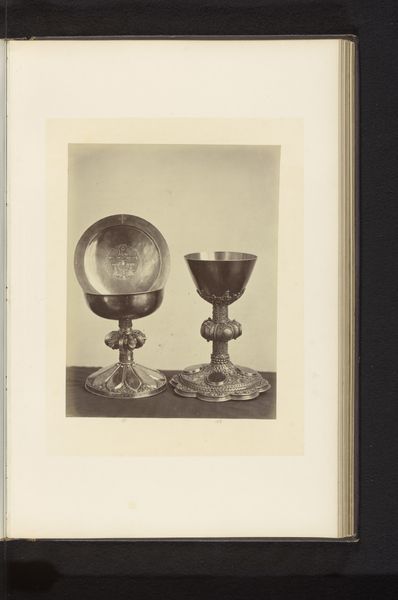

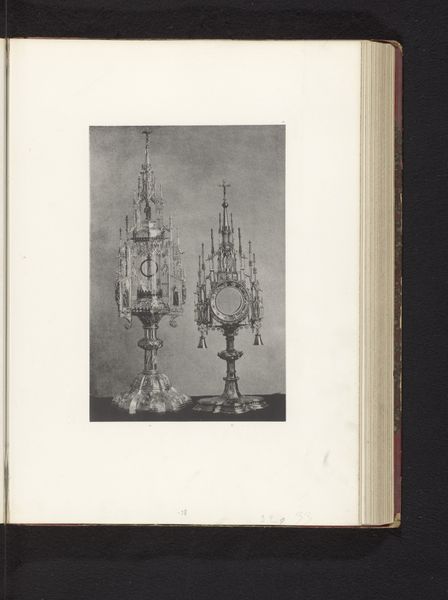

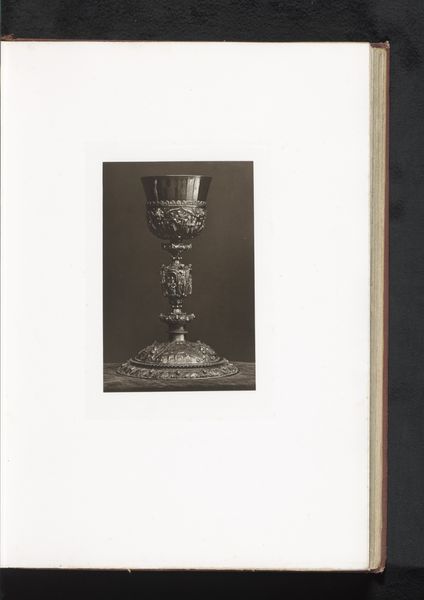

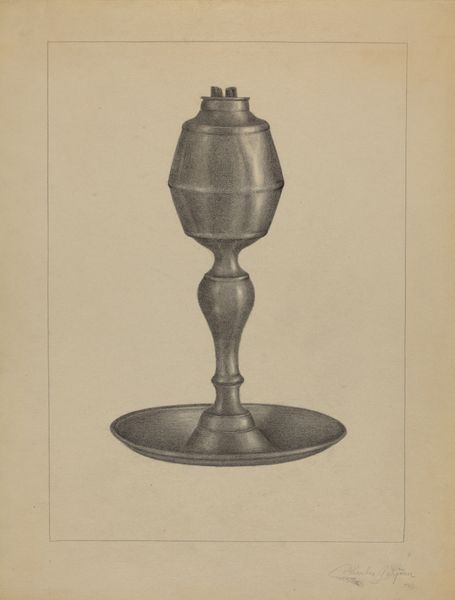

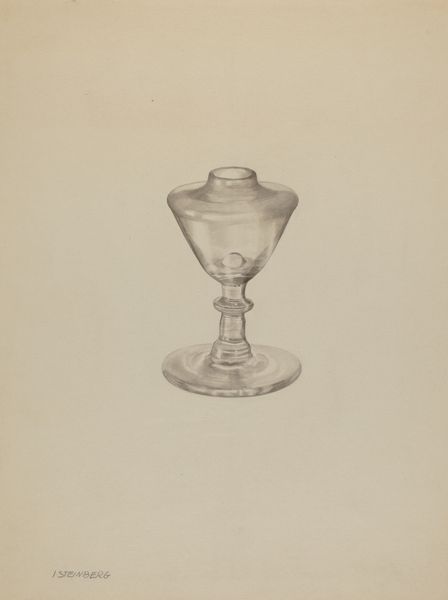

Twee kelken en een pateen, opgesteld op een tentoonstelling over religieuze objecten uit de middeleeuwen en renaissance in 1864 in Mechelen before 1866

0:00

0:00

print, photography

#

medieval

# print

#

11_renaissance

#

photography

Dimensions: height 227 mm, width 194 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is a photograph titled 'Twee kelken en een pateen, opgesteld op een tentoonstelling over religieuze objecten uit de middeleeuwen en renaissance in 1864 in Mechelen,' created before 1866 by Joseph Maes. It depicts two chalices and a paten. It feels incredibly staged and sterile to me, especially for religious objects. What do you see in it? Curator: The power of the image, for me, lies in how it attempts to capture and freeze a moment of cultural memory. Think of these objects—the chalices and the paten. They're not just vessels; they're laden with centuries of ritual, faith, and artistry. Do you notice the careful arrangement, almost a display, within the photograph itself mirroring an exhibition? Editor: Yes, now that you point it out, it's like a meta-exhibit. Almost an exhibit within an exhibit. Curator: Exactly. And in that layering, we see the attempt to preserve and present a tangible link to the medieval and Renaissance periods. The choice of photography, itself a relatively new medium, also speaks volumes. Photography claims to offer an objective truth, yet its very framing and focus impose a specific interpretation. Consider the inherent power dynamic within religious imagery-- what visual symbols evoke continuity across generations for you? Editor: It's interesting you mention "objective truth" because it feels anything but with the dark, moody lighting. I initially found it uninviting, but that was my modern viewpoint. Understanding its place within an early exhibition changes everything. I am drawn now to how different my interpretation could be in 1866. Curator: Precisely. And those shifting interpretations across time – the ability of symbols to morph and still resonate - is precisely what makes studying religious iconography so rewarding. Editor: I hadn't thought of it that way before. Thanks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.