photography

#

portrait

#

photography

#

19th century

#

genre-painting

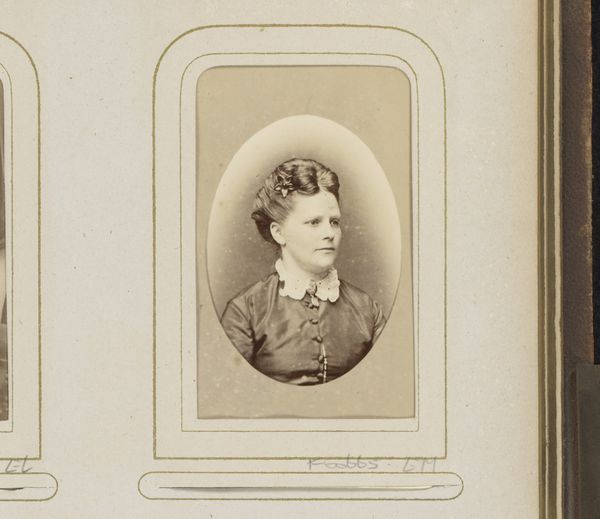

Dimensions: height 105 mm, width 64 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

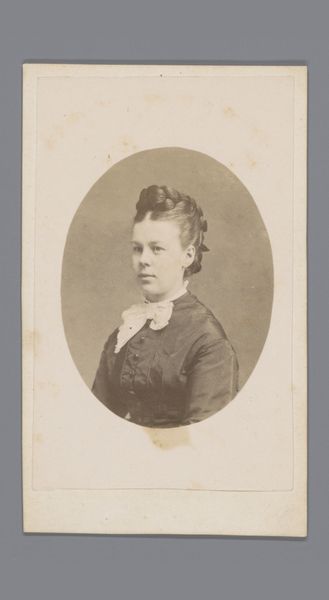

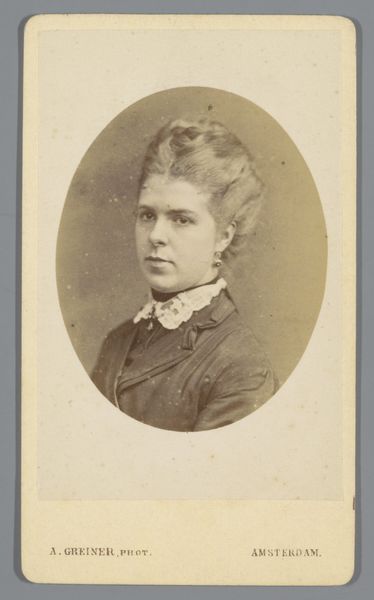

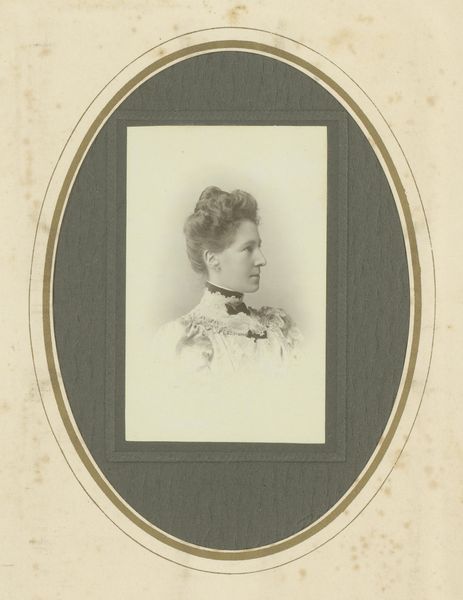

Curator: Before us, we have a photograph, "Portrait of an Unknown Woman," taken sometime between 1874 and 1892 by Cornelis Bernardus Broersma. Editor: There's an air of melancholy about her. It's a sepia-toned oval, making it feel very contained and intimate. Curator: Indeed. These photographic portraits were increasingly common amongst the bourgeoisie during that era, creating new industries around photography as commodity and also representing a visual form of self-representation, of marking identity. Here, she has adornments but not overly lavish, perhaps signalling to a specific socioeconomic stratum in society? Editor: I'm struck by the production—it's not just about wealth, but the means. Someone was doing repetitive darkroom labor to print these, popularizing what had been specialist portraiture. Look at the uniformity. The photograph isn't inherently valuable, but its means of dissemination... mass production in service of representing social class and decorum. Curator: The genre-painting context is intriguing; it mirrors societal portrayals in paintings of the era but also suggests photography entering new terrain to provide a social role previously filled by the arts. Editor: So it’s also a form of labor, on both sides of the lens. What did the photographic labour mean for representation when photography began mass distribution? Curator: Well, in thinking about gender and representation in the late 19th century, photography like this could, perhaps, be a vehicle for challenging gender stereotypes even within a constrained, commercial medium. Consider the gazes back from subject to viewer—there is a negotiation of power dynamics that also must include agency for the photographed woman. Editor: But can agency ever be disentangled from capitalist structures of production when the subject, medium, and producer are so deeply entwined? It's as much a historical document of production and access, of course, as it is of a specific individual. Curator: Fair point. Thinking about what it means for those left outside these representations would be very relevant in unpacking its social weight. It's more than a study of someone’s singular gaze and, I'd say, prompts some questions as much as answers. Editor: Exactly. To me it’s both a symbol of technological advancement and questions concerning social power dynamics around labor—of sitting for and mass producing one's image in the nineteenth century. A fascinating combination, ultimately.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.