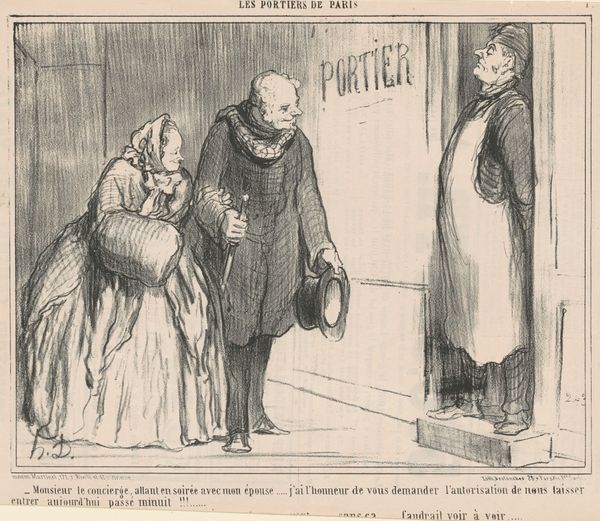

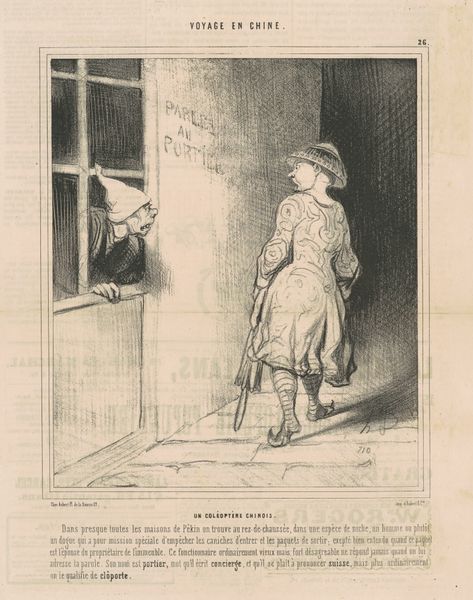

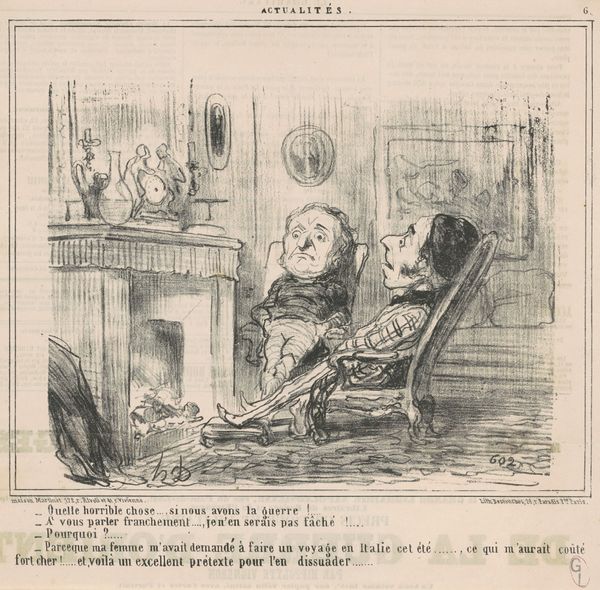

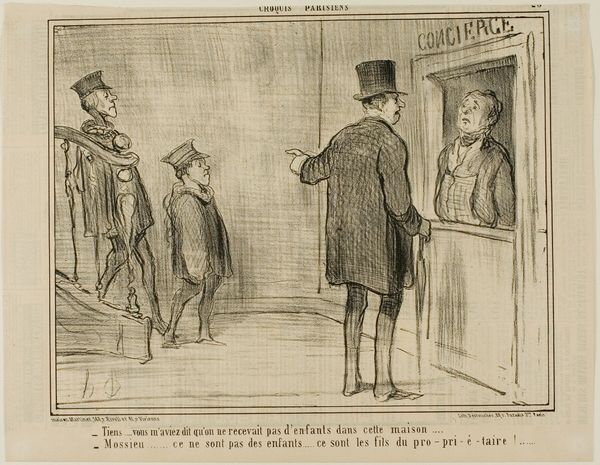

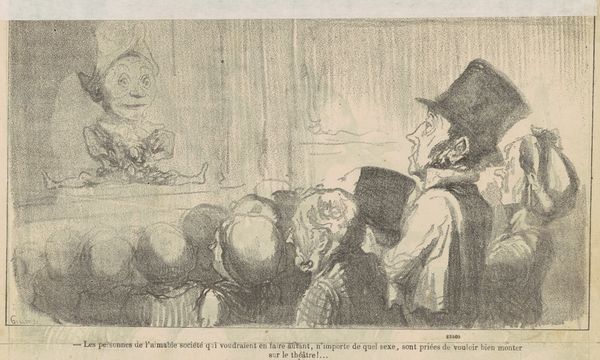

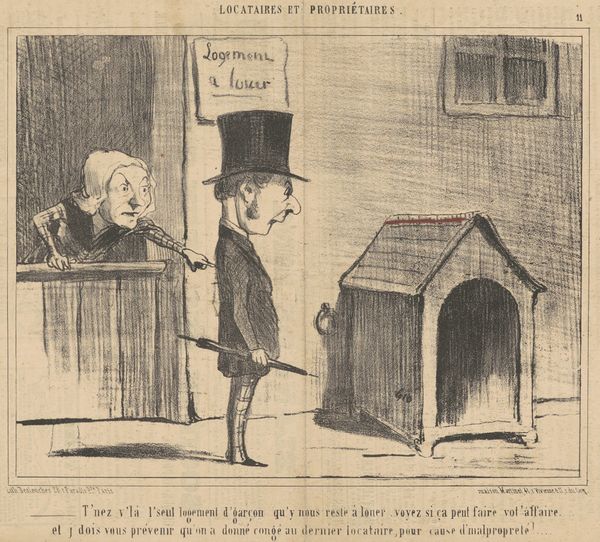

lithograph, print

#

lithograph

# print

#

caricature

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

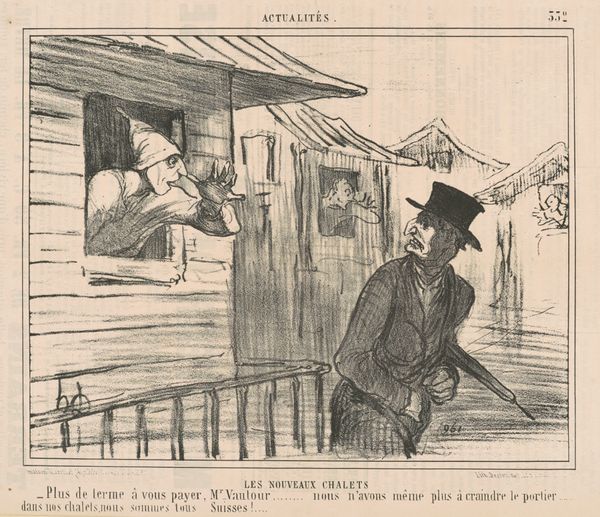

Editor: This is "Le portier de Mr Vautour," a lithograph print by Honoré Daumier from around the 19th century. The scene is stark; you've got a caricatured family being turned away by the doorman. There’s a roughness to the lines, probably inherent in lithography. I wonder how the process shaped the message? Curator: That's a keen observation. Considering the social context and the lithographic process, it allowed for mass production and distribution in newspapers and journals. This made art accessible, breaking down traditional boundaries. How does understanding that Daumier’s work would reach a large audience, versus hanging in a gallery, affect your interpretation of its message? Editor: I guess it transforms the piece into a form of social commentary, reaching people who are familiar with landlordism and class division. It must've been cheap and quick to produce lots of copies to circulate… Curator: Precisely. Daumier employed lithography as a means to expose societal inequalities and criticize the bourgeoisie. It speaks to the labor and material conditions of the medium itself—it’s art as a vehicle for change. Do you think that makes it "less" art, or a "different kind" of art? Editor: It complicates things. Traditionally we place value on the singular and the handmade, which is pretty much the opposite of cheap printing, so… I guess a different kind. I'm not sure I see it as less art. Curator: And what's gained when art focuses on representing those marginalized by the status quo, bringing labor, materials, and modes of production into consideration? Editor: It’s more honest, more grounded. It speaks to lived experiences beyond aesthetics. It’s good to think about the role and meaning behind reproducible artworks, such as this one. Thanks for broadening my view on art as a cultural object!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.