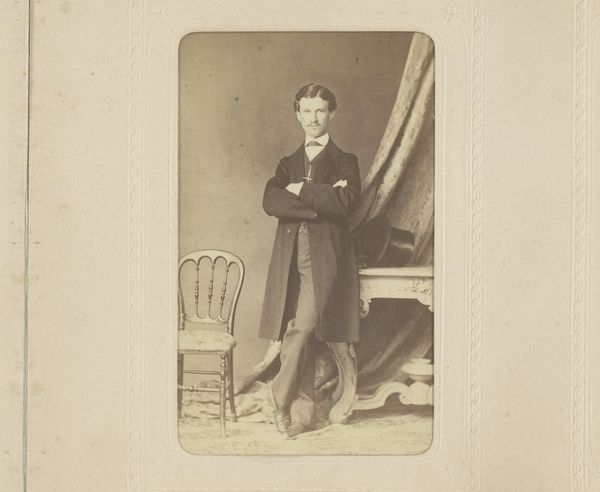

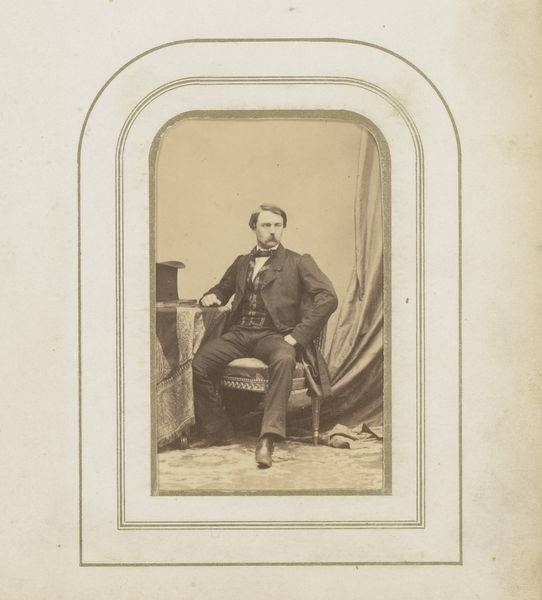

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 83 mm, width 51 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

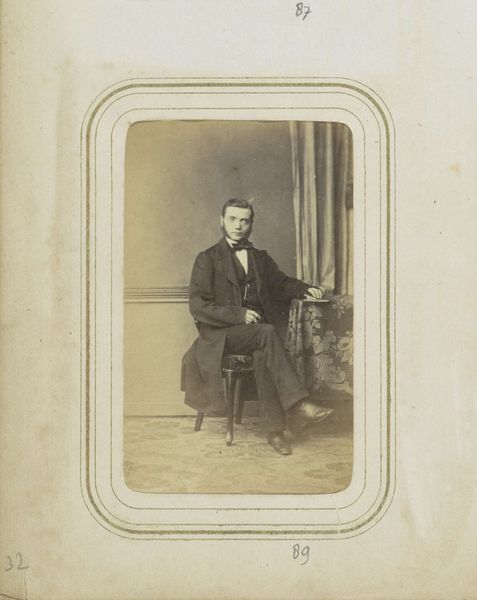

Curator: Welcome. We are looking at "Portret van een zittende man," or "Portrait of a Seated Man," a gelatin silver print by Jean Baptiste Durdik, created between 1867 and 1872. Editor: My initial impression is one of quiet confidence. The pose is so deliberate, a sort of contained energy. It evokes a certain class and self-assurance of men of that era. Curator: Indeed. Durdik masterfully utilizes light and shadow to sculpt the figure. Note the meticulous detail in the texture of his clothing, the carefully arranged folds and the strategic use of light and shadow across his visage. The diagonals created by the leg crossing cut across the vertical picture frame to create dynamism. Editor: The sitter's gaze also speaks volumes. He's looking directly at us, daring us to question his position. These photographic portraits from this period offered middle-class men opportunities to inscribe their images within history. Curator: Precisely. The composition reinforces a traditional hierarchy but subtly subverts it through the comfortable, almost casual, pose. Consider the structural elements, the chair's ornate details contrasted with the simplicity of the backdrop, it all contributes to the character study. Editor: But who was this man? Without a name, the portrait, though formally impressive, runs the risk of collapsing into the abyss of historical anonymity. What possibilities existed, what hierarchies he embodied—did they further marginalize some for the benefit of a few? Curator: While the sitter remains unknown, the technical mastery of the work and composition endure. The interplay of line, texture, and form speak beyond the mere subject. The diagonal crossing is a key element in the work’s movement, pulling us in. Editor: Agreed, while formally beautiful, it also stands as a potent reminder of the gaps in our knowledge and how art and photography participated in identity, class, and representation in the 19th century. It provokes, as great art should. Curator: A poignant reminder of art's capacity to both reveal and conceal, challenging us to continually investigate its multifaceted layers. Editor: Yes, and inviting us to reflect on how we engage with these images and the stories they do, and don't, tell about our collective past.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.