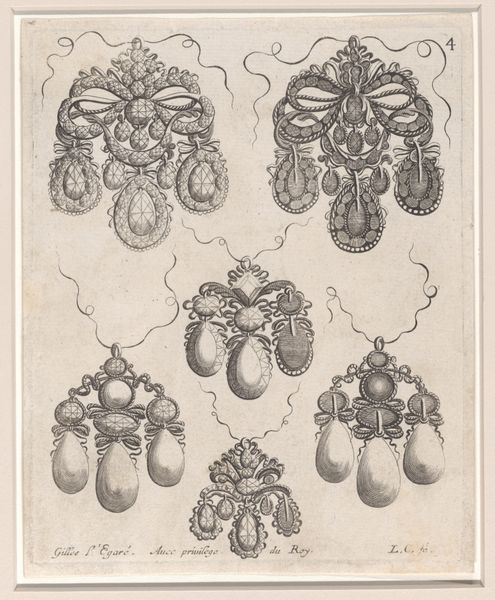

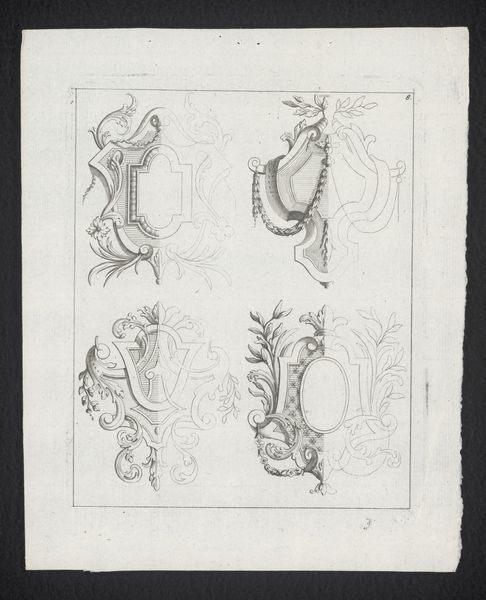

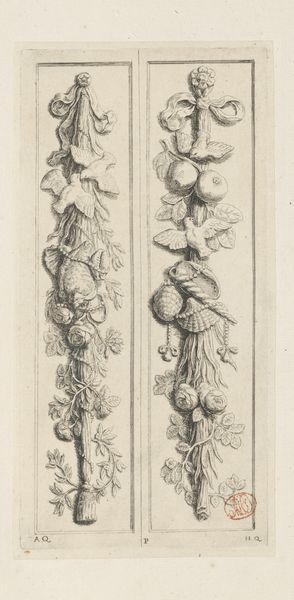

drawing, print, paper, ink, engraving

#

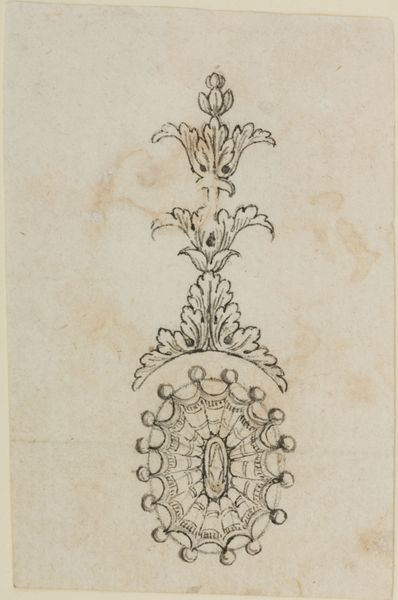

pencil drawn

#

drawing

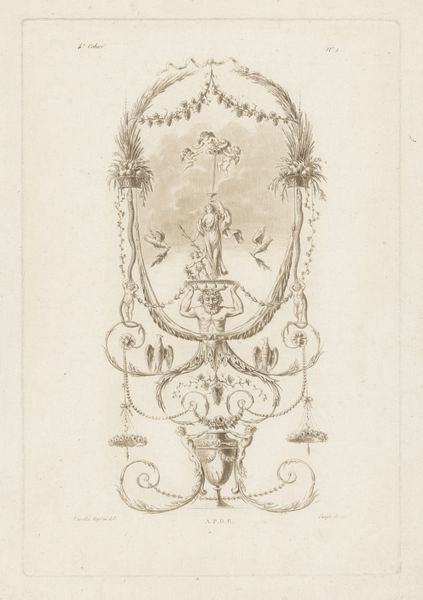

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

paper

#

ink

#

pencil drawing

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 210 mm, width 163 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

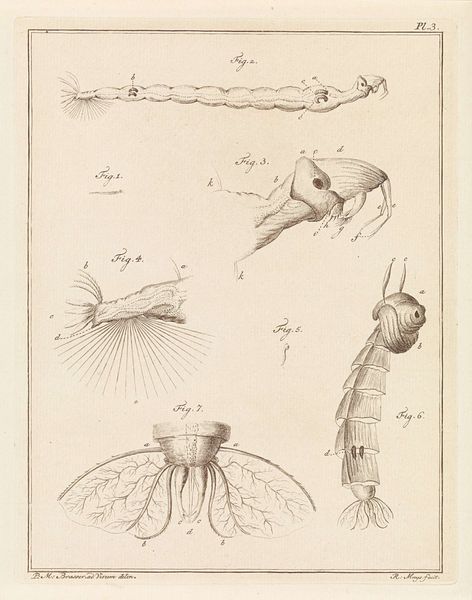

Curator: Before us we have a 1778 print titled "Schaaldier en weekdier", which translates to "Crustacean and Mollusk". It is attributed to Robbert Muys. Editor: It reminds me of anatomical drawings from an old textbook. The precise lines, the stark white background – it all gives off this air of detached scientific observation, doesn't it? There's almost a cold beauty to it. Curator: It certainly fits into that tradition. During this period, there was growing interest in documenting and classifying the natural world. Scientific illustrations served a very important role then. What do you see symbolically in the arrangement of these creatures? Editor: What strikes me is the implied hierarchy, even in something ostensibly 'objective'. The crustaceans are positioned at the top, more detailed, facing 'forward'. Then there are the mollusks, almost alien forms placed below and treated with seemingly less detail. Is that suggesting a contemporary understanding of some natural "order"? Curator: I think that's a very perceptive reading. Beyond any literal ordering, these depictions tap into older ideas about life. Consider the visual emphasis given to segmented bodies of the crustaceans above compared with the amorphous shells of the mollusks, their inner fleshy anatomy rendered rather vaguely below. Do you detect in that difference echoes of earlier theories about forms being determined either through divine ordering or spontaneous generation? Editor: Precisely. It raises interesting questions about how these images reinforce and perpetuate particular worldviews, and of what counts as worthy of study and intricate rendering. You can tell by the plate number "PL:16" on the corner that these sketches probably served a larger purpose. Curator: Indeed, the rigorous crosshatching that Muys employed certainly reflects an engagement with prevailing notions of order and natural philosophy. These weren't simply pictures. They were contributing to the systematization of the known world. The labels – "Fig. 1", "Fig. 2" etc. – all convey a sense of logic. Editor: I agree; examining works like this underscores how deeply embedded power dynamics are within knowledge production itself. Curator: Definitely, these images from 1778 highlight how closely science was intertwined with larger philosophical questions during the Enlightenment. It makes one consider what hidden meanings we read into imagery.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.