drawing, paper, watercolor, ink

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

landscape

#

paper

#

watercolor

#

ink

#

coloured pencil

#

cityscape

Dimensions: height 270 mm, width 357 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

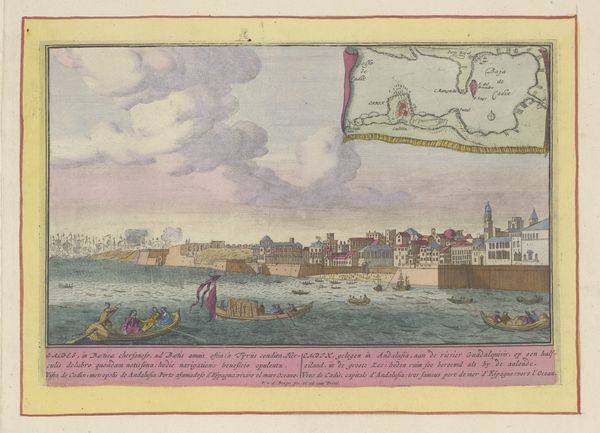

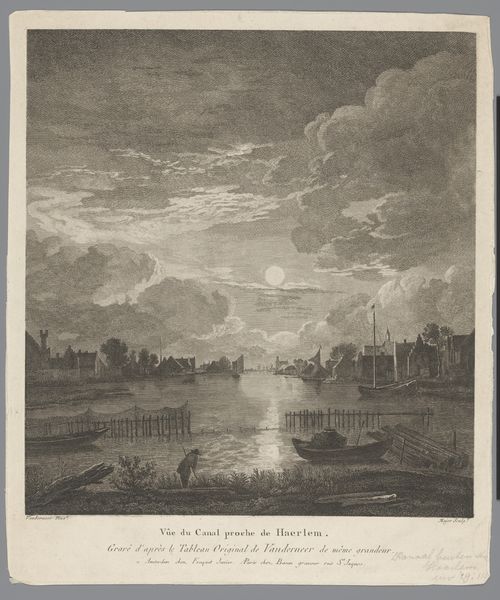

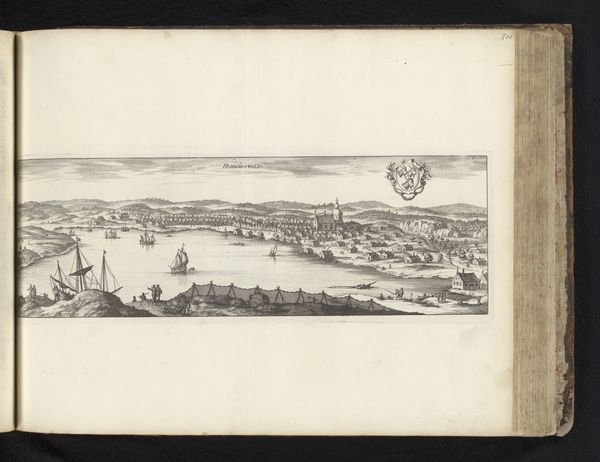

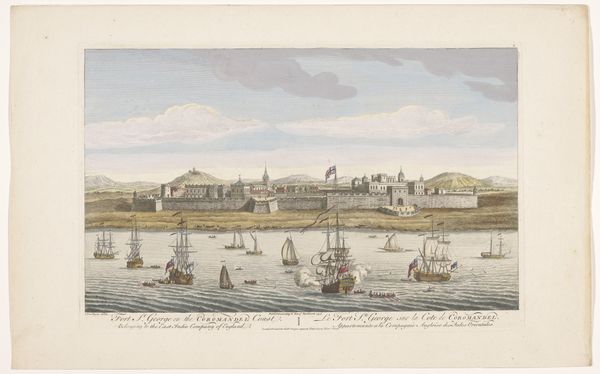

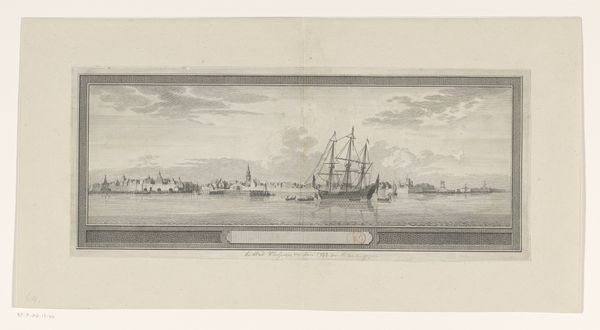

Curator: This is an interesting example of Dutch Golden Age landscape art. What strikes you most about it? Editor: Well, before diving into the history, the smoke plumes against that pale sky create an immediate sense of conflict. It’s like a beautiful scene interrupted by a brewing storm, or perhaps after one. Curator: Indeed. This work, entitled "View of Tripoli in Libya," was created around 1668. Though the creator remains anonymous, it utilizes ink, watercolor, and colored pencil on paper. As we consider Dutch global trade and colonial exploits, these depictions take on layered meanings. Editor: Precisely! It makes me consider the narratives embedded within the “cityscape” genre. The choice to include ships engulfed in what looks like cannon fire radically changes the implication of expansion and Dutch dominance, and begs the question of whose view, and at whose expense? Curator: Tripoli’s depiction can tell us a great deal about 17th century power structures, Dutch maritime ventures, and how global conflicts were consumed and disseminated back home via visual media. There’s the tension between its function as geographical document and symbolic representation of power, the role that Tripoli as an 'exotic' setting had for European audiences, not unlike similar imagery produced to celebrate imperial dominance that has had real-world social implications for the people that inhabit such spaces today. Editor: That intersection between documentation, romanticism, and social agenda is potent, even centuries later. The artwork performs cultural work then as it does now; the colonial gaze persists in how we engage such images. Even today, as the artwork rests safely behind museum glass, its violent contents call our reading habits into question. What purpose does the contemporary institution perform as guardian and exhibitor? Curator: By showing it we necessarily invite this contemporary questioning. That intersectional reading – considering the identities and politics embedded – is crucial to responsibly analyzing these works. It allows for acknowledging how past power dynamics have lasting ramifications, inviting critical reflections about representation, and prompting us to re-evaluate whose stories take center stage in artistic and historical dialogues. Editor: And I would add that this extends to the very materials. We need to inquire further what meanings the “drawing” as an intimate art form lends to large geo-political issues like conquest. A rather thought-provoking composition indeed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.