painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

portrait

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

academic-art

#

modernism

#

realism

Copyright: Public domain

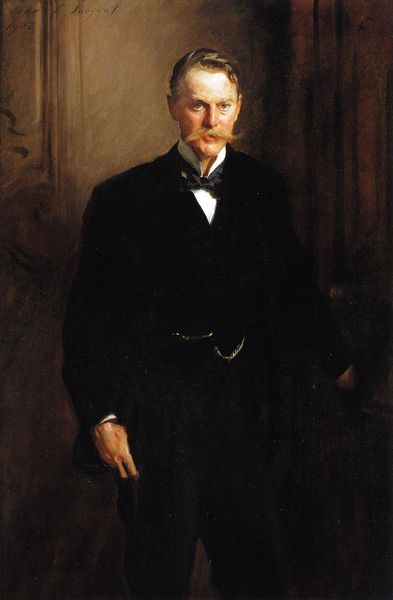

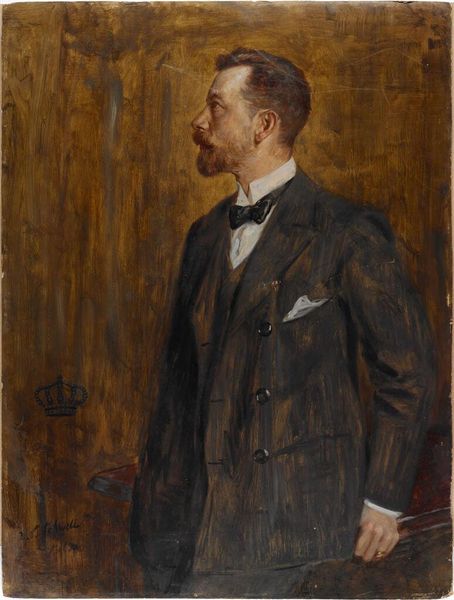

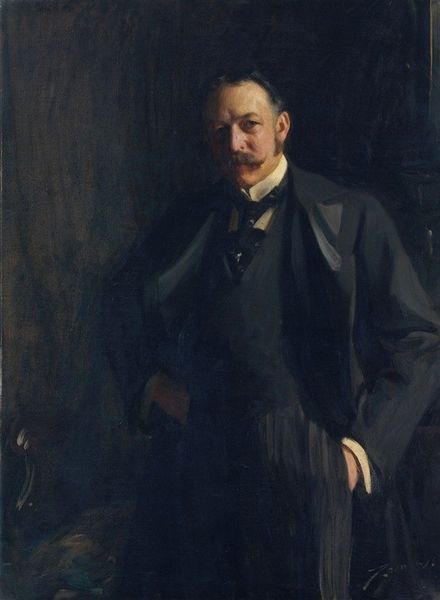

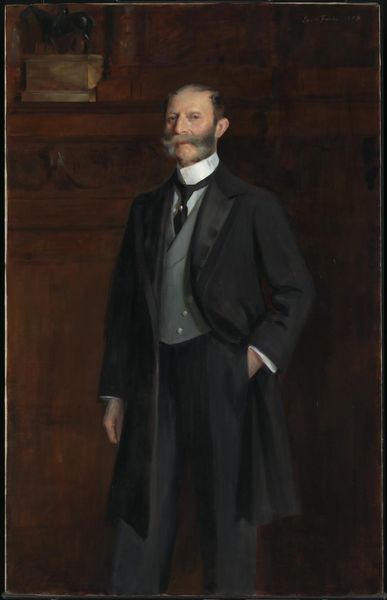

Curator: Thomas Eakins' portrait of Harrison S. Morris, painted in 1896, immediately strikes me with its almost sepia-toned palette. The somber quality of the work lends a serious tone. Editor: Absolutely, the dark hues are striking. The materiality of the suit is particularly well rendered; you can almost feel the weight of the wool and see the subtle sheen on what looks like velvet on the lapels. I am immediately drawn into its craftsmanship and the obvious quality of the materials. Curator: Right. And within the context of late 19th-century American art, this portrait sits at a crucial intersection of traditional portraiture and the emerging modernist sensibilities. Eakins, known for his realism, subtly pushes against idealized representation. It speaks volumes about the construction of masculinity in this era and who was in a position to get such portraits. Editor: Precisely, it's about that societal context and class. It is also so much about the labor embedded in the making of that suit, who was cutting the wool, tailoring, who dyed that interesting reddish-brown tie. And about how this connects to art world labor--Eakins clearly intends the visible brushwork to indicate a direct, skilled hand in production. Curator: And, looking at Morris's averted gaze, there's a psychological complexity being conveyed that moves beyond simple likeness. One might interpret that as a challenge to viewers that were also very likely wealthy and, implicitly or explicitly, very white and male. Editor: The gesture of his hand casually tucked into his pocket speaks volumes too. I think that adds another layer. What strikes me is the very self-conscious decision Eakins must have made regarding his work and production itself, the tension between a handcrafted portrait and its almost mechanical reproduction in, say, photography. It challenges the commodification of art. Curator: Yes, and Eakins invites questions regarding the politics of representation at the end of the 19th century while challenging prevailing notions of aesthetic beauty. It feels very daring for the time, and it opens pathways for future dialogues about identity in art. Editor: The portrait gives us a real window into the materials of the late 19th century as much as the sitter's mind. Curator: I agree. Eakins, always deeply interested in truth, offers us a look at that reality. Editor: He truly does.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.