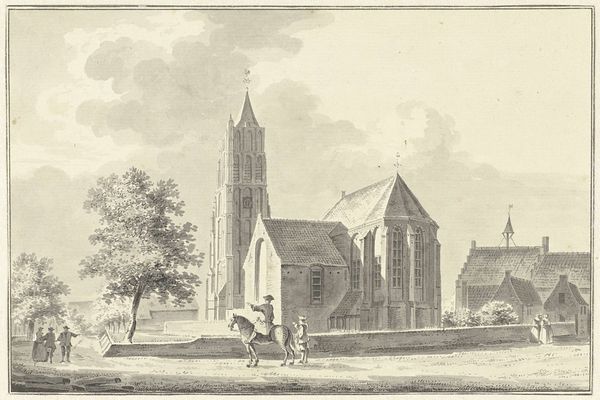

drawing, print, etching, architecture

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

neoclassicism

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 184 mm, width 245 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

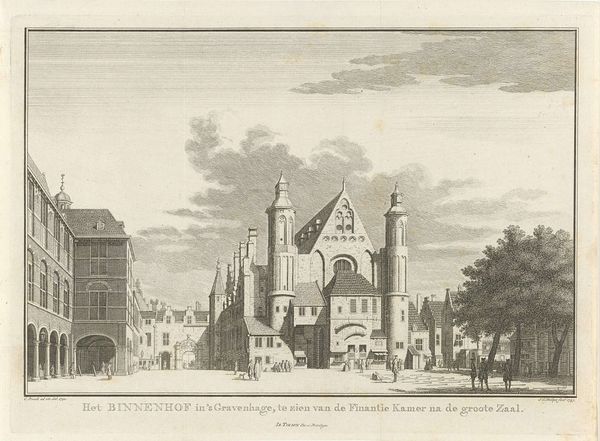

Curator: Hendrik Tavenier’s etching, "Raadhuis en weeshuis te Noordwijk," created in 1786, presents a fascinating view of Dutch architecture. Editor: There's an undeniable sense of order here. It's a muted palette, obviously, given the printmaking technique, but the architectural elements dominate – their angles, lines, and regimented placement lend a certain rigidity. Curator: Let's delve into the making. As an etching, the image relies heavily on the controlled application of acid to a metal plate. This printmaking technique allowed Tavenier to reproduce his drawing multiple times, thus disseminating this specific view and, by extension, the ideals embodied by the architecture. The buildings, the Raadhuis and orphanage of Noordwijk, demonstrate neoclassicist influences within the Dutch Golden Age. It makes you consider how materials affect how we see public spaces. Editor: Indeed. Thinking about those "public" spaces – who exactly did these buildings serve? We see what appears to be a formal, official structure, next to a building dedicated to the care of orphans. The physical closeness suggests, perhaps, a societal attempt to control and organize even its most vulnerable populations, embodying a broader social philosophy of the time. Where do those on the margins fit within this rigid architectural landscape? Curator: Consider too that while the image captures specific buildings, its creation speaks to broader shifts in artistic production and consumption. Printmaking made art more accessible, which is critical when discussing its social function. Tavenier was employed as an amanuensis - copyist- at the anatomical laboratory in Leiden. The fine lines here come from anatomical illustrations, revealing the cross-pollination of labor and knowledge. Editor: Exactly. We have a confluence of forces. Tavenier's artistic skills are deployed not just in depicting architecture but influenced by his labour. Looking at this image, the built environment speaks to the larger project of governance. It reflects not only aesthetic sensibilities, but socio-political control. Curator: In many ways, we can see it as a study of contrasting elements - control versus care. What does this duality reveal about late 18th-century Dutch society and how it saw itself? Editor: It’s a testament to the way seemingly straightforward representations can be windows into a complex web of historical, material, and societal power dynamics. Curator: Precisely; hopefully this examination allows us all to look with new insight at everyday, but fascinating images.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.