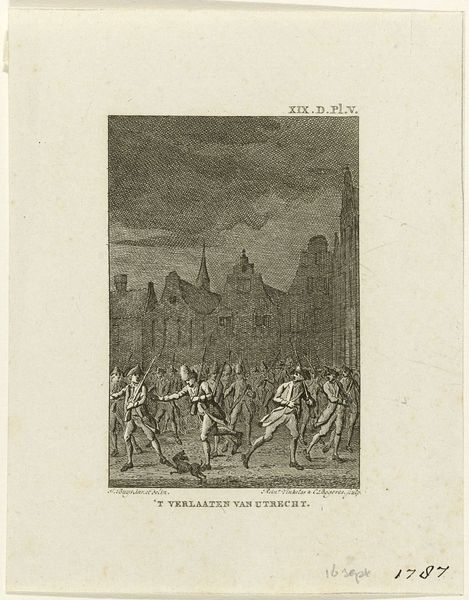

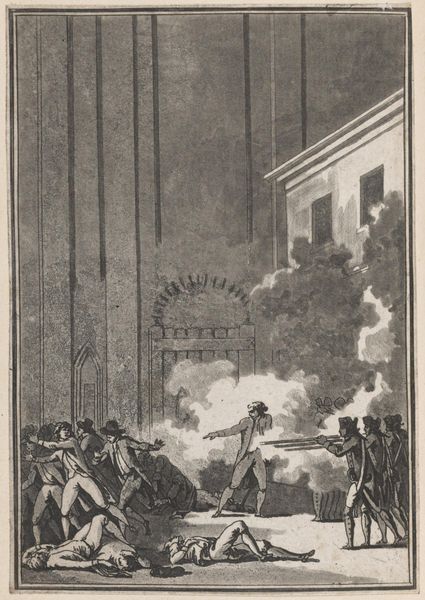

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

romanticism

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 160 mm, width 100 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

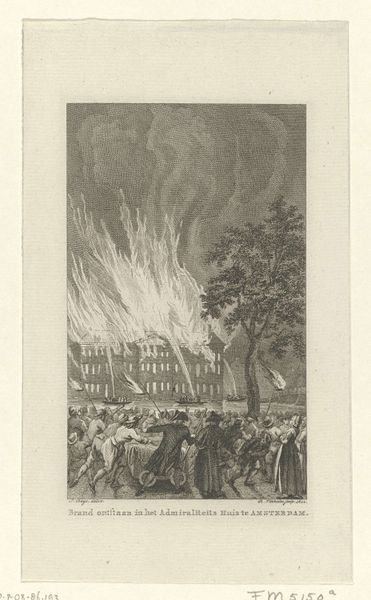

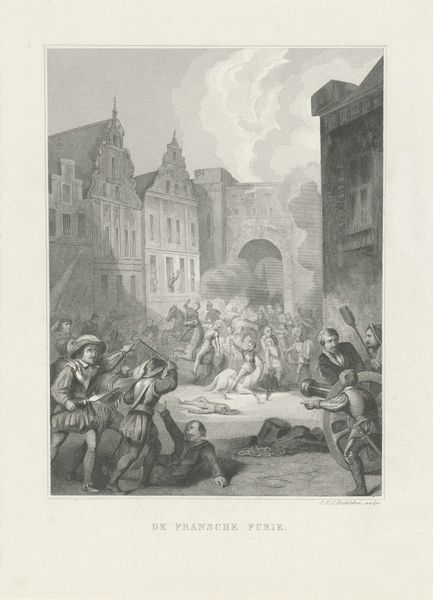

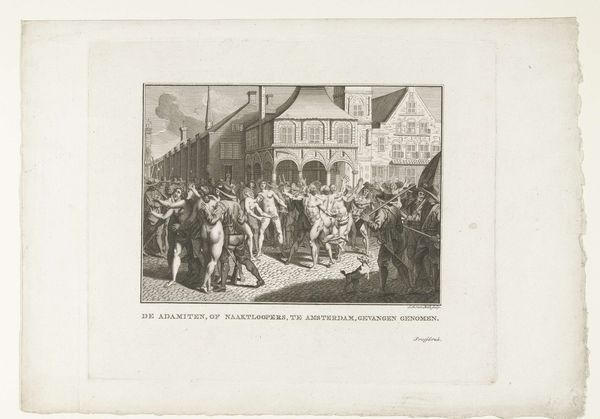

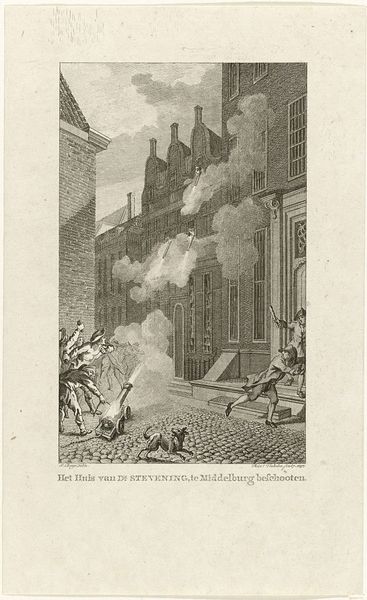

Curator: Looking at this intense engraving, “Verwoesting van 't paleis te Nymegen, door de Deenen” which roughly translates to “Destruction of the Palace at Nijmegen by the Danes,” dating from 1783 to 1795 and created by Reinier Vinkeles, my first thought is chaos. It is rather striking, don’t you think? Editor: Absolutely, you're right. It’s dominated by the dynamic figures enacting the supposed razing—bodies in frantic motion set against this stark, though meticulously rendered architectural scene consumed by fire. What I find striking, and I suppose problematic, is how these "Danes" are depicted. Curator: It's crucial to remember that this print exists within a specific material and political landscape. Vinkeles, the artist, worked primarily as an engraver of portraits and historical scenes; this piece likely served a didactic or propagandistic function. Think about the lines, the very literal work used to produce copies…consider also who commissioned these. What narrative were they aiming to perpetuate or counteract? Editor: That's a vital point. Depicting these figures as savage looters reinforces specific cultural stereotypes and justifies power dynamics rooted in historical conflict and perhaps concurrent colonial expansion as well. Notice how the figure on the right lies prone. It emphasizes power structures predicated on conquest and domination, making us question the intention behind showcasing this historical violence. What purpose does memorializing such moments of destruction serve? Curator: Indeed, engraving, as a readily reproducible medium, played a vital role in disseminating such narratives. These weren't isolated artworks destined for a select few. Their consumption across social strata informed perceptions. The choice of "line," what we might even see as a more rigid aesthetic at play, reinforces this feeling. Think about the way those lines denote depth, creating dramatic tonal contrasts across the architecture up in flames. It brings the violence to life on what is quite literally a graphic level. Editor: Yes, that’s what gives it such narrative power. In viewing this, one might question the nature of the ‘truth’ being presented, understanding that what seems like a record is instead a carefully mediated narrative shaped by identity, power, and perspective. And now this work sits here in the Rijksmuseum… it holds a loaded place as it tells more about its own production period perhaps, than it does the supposed history itself. Curator: Precisely. We should always ask ourselves not just what an artwork depicts but also *how* and *why* it came to be. Editor: Food for thought, indeed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.