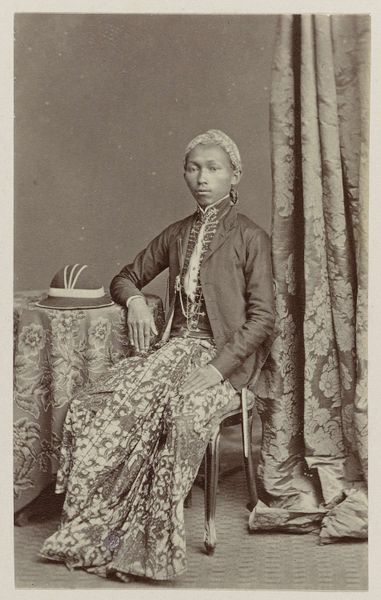

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

african-art

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 237 mm, width 175 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

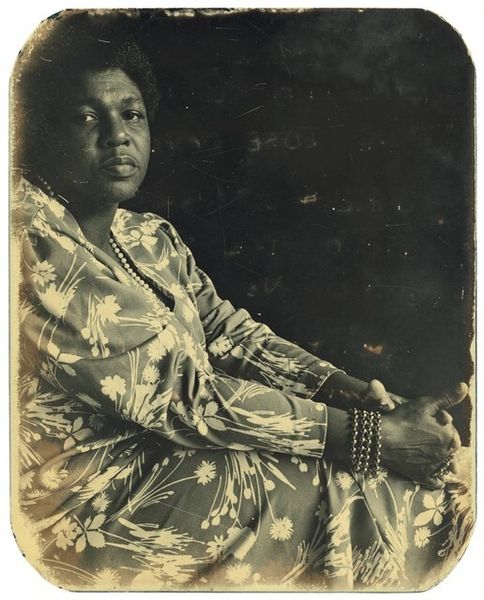

Curator: Before us, we have Friedrich Carel Hisgen’s “Portret van Jacqueline Ricket,” created between 1883 and 1884, an albumen print held at the Rijksmuseum. It strikes me as a remarkably formal, almost staged depiction. Editor: It's also striking in its texture. The floral pattern on Jacqueline's dress seems to almost merge with her skin, highlighting the interplay of fabrics, beads, and even her skin—it gives a tactile sense of labor involved in creating such pieces and of what it was to own them at the time. Curator: Yes, and the semiotics of the floral print are intriguing. Is there perhaps an intent to juxtapose the artifice of high society with natural imagery? Editor: Potentially. And, beyond the floral work, albumen printing in and of itself speaks to that interplay, of capturing organic reality with mechanical processes that are, themselves, products of human labor. Consider what goes into this photographic printing process at the time. Curator: A compelling thought. The composition itself reinforces this tension. Note the severe angle of the head, contrasting against the softness of the fabric. And observe, too, the light, illuminating only part of the face, while the hand disappears into shadow. The print quality exacerbates this effect of disappearance, absence. Editor: It truly complicates matters, doesn’t it? Looking again at the texture, knowing albumen prints, I’m imagining layers upon layers of manipulation; a carefully assembled surface to arrive at a seemingly immediate capture. Curator: Indeed. An important factor. These subtle modulations in texture work, I believe, to amplify the photograph’s underlying narrative. The photographer, like the artist, orchestrates our gaze and understanding of Jacquelina, but not necessarily with honest, simple, bare bones intention. Editor: In terms of labor then, it brings us beyond simply the work required in manufacturing Jacqueline's finery, but into a world of social performance and imposed representation. And it highlights photography's place in the global exchange of power and aesthetics, even when it poses as documentation. Curator: Quite so. Viewing the work today with such critical frameworks lets us tease apart, as you mentioned earlier, those questions about whose gaze informs the work. A fitting thought. Editor: Absolutely. It forces one to consider what images can mean at the intersection of materials, intent, and context.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.